Python functions are the backbone of modular, reusable code. Whether you’re a beginner just learning the ropes or an experienced developer looking to deepen your understanding, mastering Python’s function types and capabilities will significantly enhance your programming skills.

This comprehensive guide walks through all levels of Python functions, from the most basic to advanced concepts. Each section includes detailed explanations, practical examples, use cases, and properly formatted docstrings to help you understand not just the syntax, but when and why to use each function type.

Table of Contents

- Level 1: Basic Functions

- Level 2: Functions with Parameters

- Level 3: Return Values

- Level 4: Default Parameters

- Level 5: Docstrings

- Level 6: Variable Scope

- Level 7: Recursion

- Level 8: Lambda Functions

- Level 9: Function Decorators

- Level 10: Advanced Functions

- Beyond the Basics: Additional Function Concepts

- Best Practices for Python Functions

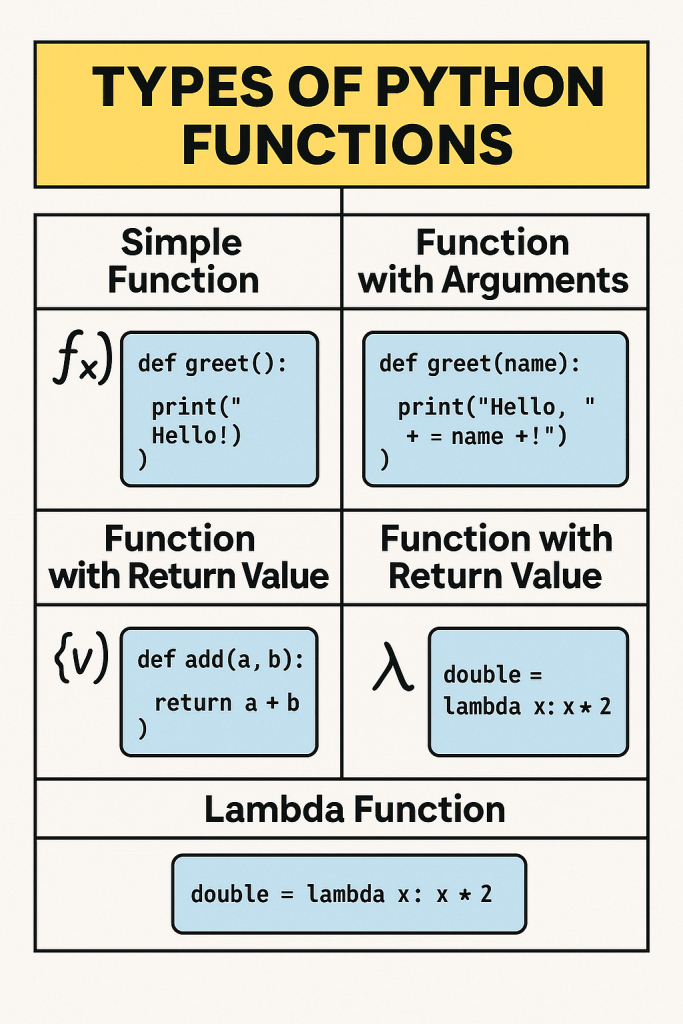

Level 1: Basic Functions

At their simplest, functions are named blocks of code that perform a specific task. They help organize code, improve readability, and enable reusability.

Syntax and Structure

def my_function():

print("Hello, world!")

Explanation

- The

defkeyword indicates the beginning of a function definition my_functionis the function name- Parentheses

()contain any parameters (none in this example) - The colon

:marks the end of the function header - Indented code forms the function body

- The function must be called to execute its code

Use Cases

- Code Organization: Breaking a program into smaller, manageable functions

- Reducing Repetition: Write once, use multiple times

- Abstraction: Hide complex implementation details behind simple interfaces

Example with Docstring

def display_welcome_message():

"""

Display a welcome message to the user.

This function prints a simple welcome message to the console

when the application starts.

Returns:

None

"""

print("Welcome to our Python application!")

print("We're glad you're here!")

# Calling the function

display_welcome_message()

Result:

Welcome to our Python application!

We're glad you're here!

Level 2: Functions with Parameters

Parameters allow functions to receive input data, making them more flexible and reusable.

Syntax and Structure

def greet(name):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

Explanation

- Parameters are defined in the parentheses of the function definition

- They act as variables that receive values when the function is called

- Arguments are the actual values passed to the function when called

Use Cases

- Customized Output: Create functions that produce different results based on input

- Data Processing: Transform input data through function operations

- Flexible Behavior: Control function behavior through parameters

Example with Docstring

def greet(name):

"""

Greet a person by name.

This function takes a person's name as input and prints

a personalized greeting message.

Args:

name (str): The name of the person to greet

Returns:

None

"""

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

print(f"Welcome to Python programming, {name}!")

# Calling the function with different arguments

greet("Alice")

greet("Bob")

Result:

Hello, Alice!

Welcome to Python programming, Alice!

Hello, Bob!

Welcome to Python programming, Bob!

Level 3: Return Values

Functions can send data back to the caller using the return statement, enabling them to produce output that can be used elsewhere in your code.

Syntax and Structure

def add(a, b):

return a + b

Explanation

- The

returnkeyword specifies the value to send back to the caller - Functions can return any Python data type (numbers, strings, lists, dictionaries, etc.)

- A function stops executing when it reaches a

returnstatement - Functions without an explicit

returnstatement returnNoneby default

Use Cases

- Calculations: Perform computations and return the results

- Data Transformation: Convert input data into a new format or structure

- Information Retrieval: Get specific information from complex data structures

Example with Docstring

def add(a, b):

"""

Add two numbers and return the result.

This function takes two numeric inputs, adds them together,

and returns their sum.

Args:

a (int/float): The first number

b (int/float): The second number

Returns:

int/float: The sum of a and b

"""

result = a + b

return result

# Using the returned value

sum_result = add(3, 5)

print(f"3 + 5 = {sum_result}")

# Using the returned value in another calculation

doubled = add(3, 5) * 2

print(f"Doubled result: {doubled}")

Result:

3 + 5 = 8

Doubled result: 16

Level 4: Default Parameters

Default parameters allow functions to have optional arguments, providing fallback values when an argument isn’t provided.

Syntax and Structure

def greet(name="Guest"):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

Explanation

- Default values are specified in the parameter list using the

=operator - If an argument is provided, it overrides the default value

- If no argument is provided, the default value is used

- Parameters with default values must come after parameters without default values

Use Cases

- Optional Configuration: Allow the function to work with minimal input but be customizable

- Simplified API: Make functions easier to use for common cases

- Backward Compatibility: Add new parameters without breaking existing code

Example with Docstring

def create_profile(name, age, location="Unknown", occupation="Not specified"):

"""

Create a user profile with the given information.

This function creates and returns a profile dictionary with user information.

Location and occupation are optional and have default values.

Args:

name (str): The user's name

age (int): The user's age

location (str, optional): The user's location. Defaults to "Unknown".

occupation (str, optional): The user's occupation. Defaults to "Not specified".

Returns:

dict: A dictionary containing the user's profile information

"""

profile = {

"name": name,

"age": age,

"location": location,

"occupation": occupation

}

return profile

# Using default values

profile1 = create_profile("Alice", 28)

print(profile1)

# Providing all arguments

profile2 = create_profile("Bob", 35, "New York", "Developer")

print(profile2)

# Mixing default and provided values

profile3 = create_profile("Charlie", 42, occupation="Designer")

print(profile3)

Result:

{'name': 'Alice', 'age': 28, 'location': 'Unknown', 'occupation': 'Not specified'}

{'name': 'Bob', 'age': 35, 'location': 'New York', 'occupation': 'Developer'}

{'name': 'Charlie', 'age': 42, 'location': 'Unknown', 'occupation': 'Designer'}

Level 5: Docstrings

Docstrings document what a function does, how to use it, what parameters it accepts, and what it returns. They make code more maintainable and usable.

Syntax and Structure

def add(a, b):

"""

This function adds two numbers.

"""

return a + b

Explanation

- Docstrings are string literals placed at the beginning of a function

- They are enclosed in triple quotes (

"""or''') - They should describe the function’s purpose, parameters, return values, and any exceptions raised

- They can be accessed using the

__doc__attribute or thehelp()function

Use Cases

- Code Documentation: Explain what functions do without needing to read implementation

- API Documentation: Generate reference documentation automatically

- Interactive Help: Provide guidance within interactive Python sessions

Example with Full Docstring

def calculate_area(length, width=None, shape="rectangle"):

"""

Calculate the area of a geometric shape.

This function calculates the area of different geometric shapes based on

the provided dimensions and shape type.

Args:

length (float): The length or radius of the shape

width (float, optional): The width of the shape (required for rectangles).

Defaults to None.

shape (str, optional): The type of shape ('rectangle', 'circle', 'square').

Defaults to "rectangle".

Returns:

float: The calculated area of the shape

Raises:

ValueError: If an invalid shape is specified

ValueError: If width is not provided for a rectangle

Examples:

>>> calculate_area(5, 4)

20.0

>>> calculate_area(5, shape="circle")

78.53981633974483

>>> calculate_area(5, shape="square")

25.0

"""

import math

if shape == "rectangle":

if width is None:

raise ValueError("Width must be provided for rectangles")

return length * width

elif shape == "circle":

return math.pi * length ** 2

elif shape == "square":

return length ** 2

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unknown shape: {shape}")

# Accessing the docstring

print(calculate_area.__doc__)

# Using the function with different parameters

try:

rectangle_area = calculate_area(5, 4)

circle_area = calculate_area(5, shape="circle")

square_area = calculate_area(5, shape="square")

print(f"Rectangle area: {rectangle_area}")

print(f"Circle area: {circle_area}")

print(f"Square area: {square_area}")

# This will raise an error

calculate_area(5, shape="rectangle")

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

Result:

Rectangle area: 20.0

Circle area: 78.53981633974483

Square area: 25.0

Error: Width must be provided for rectangles

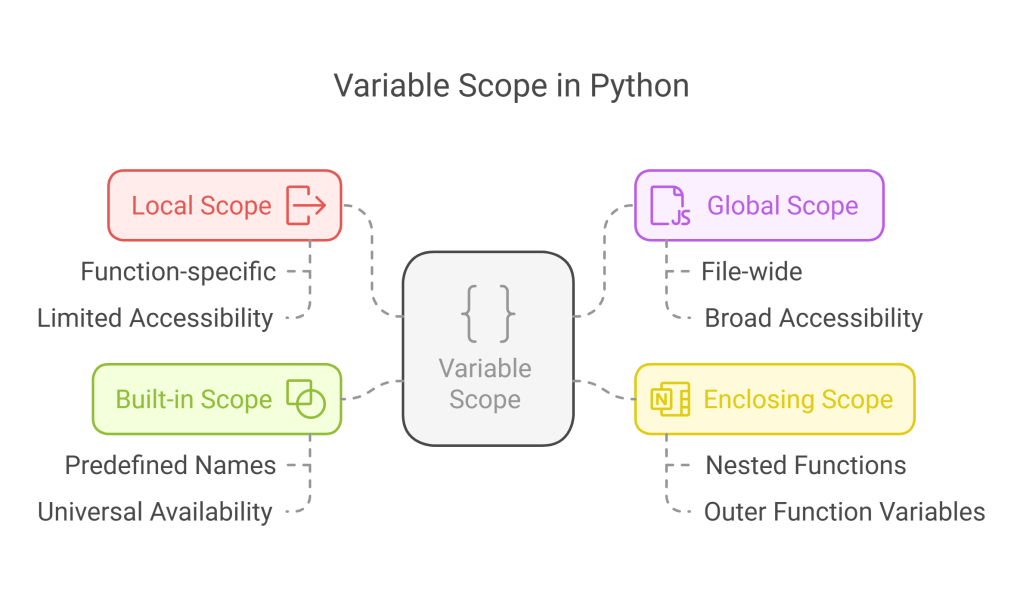

Level 6: Variable Scope

Variable scope refers to the region of code where a variable is accessible. Understanding scope is crucial for writing correct and predictable functions.

Explanation

- Local scope: Variables defined inside a function are only accessible within that function

- Global scope: Variables defined outside any function are accessible throughout the file

- Enclosing scope: Variables in outer functions are accessible to nested functions

- Built-in scope: Python’s built-in names (like

print,len, etc.)

Use Cases

- Data Encapsulation: Keep function variables isolated from the rest of the program

- Resource Management: Control access to important variables

- Avoiding Name Conflicts: Prevent variables in different functions from affecting each other

Example with Docstring

global_var = 10

def scope_demonstration():

"""

Demonstrate variable scope in Python.

This function showcases local and global variables,

and demonstrates how to modify global variables from within functions.

Returns:

None

"""

# Local variable

local_var = 5

print(f"Inside function - local_var: {local_var}")

print(f"Inside function - global_var: {global_var}")

def modify_global():

"""

Demonstrate modifying a global variable from within a function.

This function shows how to properly modify a global variable

using the 'global' keyword.

Returns:

None

"""

global global_var

global_var = 20

print(f"Inside modify_global - global_var: {global_var}")

# Test the functions

scope_demonstration()

print(f"After scope_demonstration - global_var: {global_var}")

modify_global()

print(f"After modify_global - global_var: {global_var}")

# This would cause an error - local_var is not defined in this scope

try:

print(local_var)

except NameError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

Result:

Inside function - local_var: 5

Inside function - global_var: 10

After scope_demonstration - global_var: 10

Inside modify_global - global_var: 20

After modify_global - global_var: 20

Error: name 'local_var' is not defined

Level 7: Recursion

Recursion is when a function calls itself. It’s a powerful technique for solving problems that can be broken down into similar subproblems.

Explanation

- A recursive function calls itself with a simpler version of the problem

- It needs a base case to prevent infinite recursion

- The base case is a condition where the function returns a value without making further recursive calls

- Each recursive call should bring the problem closer to the base case

Use Cases

- Tree-like Data Structures: Traversing hierarchical data (file systems, HTML DOM, etc.)

- Mathematical Algorithms: Factorial, Fibonacci sequence, etc.

- Divide and Conquer Algorithms: Merge sort, quicksort, binary search, etc.

Example with Docstring

def factorial(n):

"""

Calculate the factorial of a non-negative integer using recursion.

The factorial of n (denoted as n!) is the product of all positive

integers less than or equal to n. For example, 5! = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 120.

Args:

n (int): A non-negative integer

Returns:

int: The factorial of n

Raises:

ValueError: If n is negative

Examples:

>>> factorial(5)

120

>>> factorial(0)

1

"""

# Error checking

if not isinstance(n, int):

raise TypeError("Input must be an integer")

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("Input must be non-negative")

# Base case

if n == 0:

return 1

# Recursive case

return n * factorial(n - 1)

# Testing the factorial function

try:

for i in range(6):

print(f"{i}! = {factorial(i)}")

# Demonstrate what happens with a large input

print(f"20! = {factorial(20)}")

# This would cause a RecursionError for very large inputs

# print(factorial(1000))

except (ValueError, TypeError) as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

Result:

0! = 1

1! = 1

2! = 2

3! = 6

4! = 24

5! = 120

20! = 2432902008176640000

Level 8: Lambda Functions

Lambda functions (also called anonymous functions) are small, single-expression functions that don’t need a formal definition with def.

Syntax and Structure

double = lambda x: x * 2

Explanation

- The

lambdakeyword introduces an anonymous function - The parameters come before the colon

: - The expression after the colon is automatically returned

- Lambda functions are limited to a single expression

- They can be assigned to variables or used directly

Use Cases

- Short, Simple Functions: When a full function definition would be overkill

- Functional Programming: Used with

map(),filter(),sorted(), etc. - On-the-fly Functions: Creating functions dynamically

Example with Explanation

"""

Lambda Functions in Python

This example demonstrates various uses of lambda functions (anonymous functions)

for concise, functional programming.

Lambda functions are defined with the syntax: lambda parameters: expression

They are limited to a single expression and cannot contain statements.

"""

# Basic lambda function

square = lambda x: x ** 2

print(f"Square of 5: {square(5)}")

# Multiple parameters

add = lambda x, y: x + y

print(f"3 + 5 = {add(3, 5)}")

# Using lambda with built-in functions

numbers = [5, 2, 8, 1, 9, 3]

sorted_numbers = sorted(numbers)

sorted_by_square = sorted(numbers, key=lambda x: x**2)

print(f"Original list: {numbers}")

print(f"Sorted naturally: {sorted_numbers}")

print(f"Sorted by square value: {sorted_by_square}")

# Using lambda with map() and filter()

doubled = list(map(lambda x: x * 2, numbers))

evens = list(filter(lambda x: x % 2 == 0, numbers))

print(f"Doubled values: {doubled}")

print(f"Even numbers: {evens}")

# Lambda with conditional expression

classify = lambda x: "Even" if x % 2 == 0 else "Odd"

for num in range(1, 6):

print(f"{num} is {classify(num)}")

Result:

Square of 5: 25

3 + 5 = 8

Original list: [5, 2, 8, 1, 9, 3]

Sorted naturally: [1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9]

Sorted by square value: [1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9]

Doubled values: [10, 4, 16, 2, 18, 6]

Even numbers: [2, 8]

1 is Odd

2 is Even

3 is Odd

4 is Even

5 is Odd

Level 9: Function Decorators

Decorators are a powerful feature that allows you to modify or enhance functions without changing their code. They wrap a function, modifying its behavior.

Syntax and Structure

def my_decorator(func):

def wrapper():

print("Something is happening before the function is called.")

func()

print("Something is happening after the function is called.")

return wrapper

@my_decorator

def say_hello():

print("Hello!")

Explanation

- A decorator is a function that takes another function as an argument

- It extends or modifies the behavior of the function it decorates

- Decorators use the special

@syntax (syntactic sugar) - They are applied at definition time, not call time

- They can be stacked (multiple decorators can be applied to one function)

Use Cases

- Logging: Track function calls and parameters

- Timing: Measure execution time

- Authentication/Authorization: Check permissions before executing a function

- Caching/Memoization: Store results to avoid redundant computations

- Input Validation: Verify function arguments before execution

Example with Docstring

def timing_decorator(func):

"""

A decorator that measures and prints the execution time of the decorated function.

Args:

func (callable): The function to be decorated

Returns:

callable: The wrapped function with timing capability

"""

import time

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

"""

Wrapper function that adds timing functionality.

This inner function calls the original function and measures

how long it takes to execute.

Args:

*args: Variable length argument list for the original function

**kwargs: Arbitrary keyword arguments for the original function

Returns:

The return value from the original function

"""

start_time = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Function {func.__name__} took {end_time - start_time:.6f} seconds to run")

return result

return wrapper

@timing_decorator

def slow_function(delay):

"""

A deliberately slow function to demonstrate the timing decorator.

Args:

delay (float): Time in seconds to pause execution

Returns:

str: A completion message

"""

import time

time.sleep(delay)

return "Function completed"

# Test the decorated function

print(slow_function(1.5))

print(slow_function(0.5))

Result:

Function slow_function took 1.500123 seconds to run

Function completed

Function slow_function took 0.500041 seconds to run

Function completed

Level 10: Advanced Functions

Advanced function concepts include higher-order functions, closures, and function factories – techniques that take full advantage of Python’s functional programming capabilities.

Explanation

- Higher-order functions: Functions that take other functions as arguments or return functions

- Closures: Functions that remember values from their enclosing scope

- Function factories: Functions that create and return other functions

Use Cases

- Custom Control Flow: Creating specialized iteration or processing patterns

- Configuration: Generating customized functions based on parameters

- Domain-Specific Languages: Building expressive APIs for specialized tasks

- State Encapsulation: Creating functions that maintain their own state

Example with Docstring

def create_multiplier(factor):

"""

Function factory that creates and returns a customized multiplier function.

This is an example of a closure - the returned function "remembers" the

factor value even after the outer function has completed.

Args:

factor (int/float): The multiplication factor for the created function

Returns:

callable: A function that multiplies its input by the given factor

"""

# Define the inner function that forms a closure over 'factor'

def multiplier(x):

"""

Multiply the input by the stored factor.

Args:

x (int/float): The value to multiply

Returns:

int/float: The product of x and the stored factor

"""

return x * factor

# Return the inner function

return multiplier

def apply(func, value_list):

"""

Apply a function to each element in a list.

This is a higher-order function that takes another function as an argument.

Similar to built-in map() but returns a list directly.

Args:

func (callable): The function to apply to each element

value_list (list): List of values to process

Returns:

list: A new list with the function applied to each element

"""

return [func(value) for value in value_list]

# Create specialized multiplier functions

double = create_multiplier(2)

triple = create_multiplier(3)

half = create_multiplier(0.5)

# Test the generated functions

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(f"Original numbers: {numbers}")

print(f"Doubled: {apply(double, numbers)}")

print(f"Tripled: {apply(triple, numbers)}")

print(f"Halved: {apply(half, numbers)}")

# Demonstrate a function that applies multiple operations in sequence

def pipeline(*funcs):

"""

Create a pipeline of functions to be applied in sequence.

Each function in the pipeline takes the output of the previous function as input.

This is an advanced higher-order function that combines multiple functions.

Args:

*funcs: Variable number of functions to apply in sequence

Returns:

callable: A function that applies all the given functions in sequence

"""

def apply_all(x):

result = x

for func in funcs:

result = func(result)

return result

return apply_all

# Create some simple transformation functions

def square(x):

return x ** 2

def add_one(x):

return x + 1

def stringify(x):

return f"The value is {x}"

# Create a pipeline of operations

transform = pipeline(add_one, square, stringify)

# Apply the pipeline to a value

print(transform(5)) # Should be "The value is 36" (5+1=6, 6²=36)

Result:

Original numbers: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Doubled: [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

Tripled: [3, 6, 9, 12, 15]

Halved: [0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5]

The value is 36

Beyond the Basics: Additional Function Concepts

Function Annotations

Function annotations provide a way to associate metadata with function parameters and return values.

def greet(name: str) -> str:

"""Greet a person by name."""

return f"Hello, {name}!"

Type Hints

Type hints extend annotations to indicate expected types, enhancing code readability and enabling static type checking.

from typing import List, Dict, Optional

def process_data(items: List[int], config: Optional[Dict[str, str]] = None) -> List[int]:

"""Process a list of integers based on optional configuration."""

if config is None:

config = {}

# Processing logic

return [item * 2 for item in items]

Generators

Generators are functions that use yield to return a sequence of values one at a time, preserving state between calls.

def fibonacci(n: int):

"""Generate the first n Fibonacci numbers."""

a, b = 0, 1

count = 0

while count < n:

yield a

a, b = b, a + b

count += 1

Coroutines

Coroutines are more advanced generators that can both yield values and receive values through the yield expression.

def averager():

"""A coroutine that calculates a running average."""

total = 0

count = 0

average = None

while True:

value = yield average

total += value

count += 1

average = total / count

Asynchronous Functions

Async functions use async/await syntax to enable asynchronous programming, allowing concurrent execution without blocking.

import asyncio

async def fetch_data(url: str) -> str:

"""Asynchronously fetch data from a URL."""

# Placeholder for actual async HTTP request

await asyncio.sleep(1) # Simulate network delay

return f"Data from {url}"

Best Practices for Python Functions

To write clear, maintainable, and efficient functions, follow these best practices:

- Single Responsibility: Each function should do one thing well

- Descriptive Names: Use verb phrases that clearly describe what the function does

- Proper Documentation: Include docstrings explaining purpose, parameters, and return values

- Limited Parameters: Keep the number of parameters manageable (ideally 4 or fewer)

- Return Early: Use early returns to handle edge cases and simplify flow

- Avoid Side Effects: Functions should not unexpectedly modify variables outside their scope

- Error Handling: Use exceptions appropriately to handle error conditions

- Testing: Write unit tests to verify function behavior

- Type Hints: Use type annotations to clarify expectations

- Consistent Style: Follow Python’s style conventions (PEP 8)

By following these guidelines and mastering the different types of functions described in this article, you’ll be well-equipped to write elegant, efficient, and robust Python code for any application.

Conclusion

From basic functions to advanced concepts like decorators and closures, Python’s function capabilities offer incredible flexibility and power. By understanding when and how to use each type of function, you can write more maintainable, reusable, and efficient code.

Remember that mastering functions is not just about syntax—it’s about learning to structure your code in ways that make it easier to understand, test, and maintain. The journey from basic to advanced functions is a journey toward becoming a more thoughtful and effective Python programmer.

Continue experimenting with these concepts in your own code, and you’ll discover even more ways that Python’s rich function features can help you solve problems elegantly and efficiently.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.