Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly evolved from a niche academic pursuit into a transformative force reshaping industries and daily life. From the algorithms powering search engines and recommendation systems to the complex models enabling autonomous vehicles and natural language understanding, AI systems are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Building these powerful systems, however, is a complex endeavor involving multiple stages, technologies, and considerations. To manage this complexity, AI development often follows a layered architectural approach, breaking down the system into distinct, manageable components, each with a specific function.

Understanding this layered structure is crucial for anyone involved in developing, deploying, or utilizing AI. It provides a framework for comprehending how different elements – from the underlying hardware to the user-facing application – interact and contribute to the overall functionality. This article delves into a common conceptualization of AI model architecture, exploring seven distinct layers that represent the journey from physical infrastructure to intelligent application deployment. While variations exist, this seven-layer model offers a comprehensive view of the critical components involved in bringing AI to life.

We will explore each layer in detail:

- Physical Hardware Layer: The bedrock upon which all AI computation rests.

- Data Link Layer: The bridge connecting AI models to real-world applications and ensuring operational efficiency.

- Computation Layer: The engine room where inference, processing, and logical execution occur.

- Knowledge Layer: The mechanism for augmenting AI with external information and reasoning capabilities.

- Learning Layer: The core where models are trained and optimized using data.

- Representation Layer: The crucial stage of transforming raw data into AI-readable formats.

- Application Layer: The final interface through which users or systems interact with the AI.

By dissecting each layer, we gain insight into the intricate processes, technologies, and challenges involved in building and deploying modern AI systems.

Layer 1: The Physical Hardware Layer – The Foundation of Computation

At the very base of any AI system lies the Physical Hardware Layer. This is the tangible foundation, the collection of silicon, circuits, and storage that provides the raw computational power necessary for training and running complex AI models. Without robust and specialized hardware, the sophisticated algorithms that define modern AI would remain purely theoretical. This layer is not just about processing power; it encompasses storage solutions, high-speed networking, and specialized accelerators designed to handle the unique demands of AI workloads.

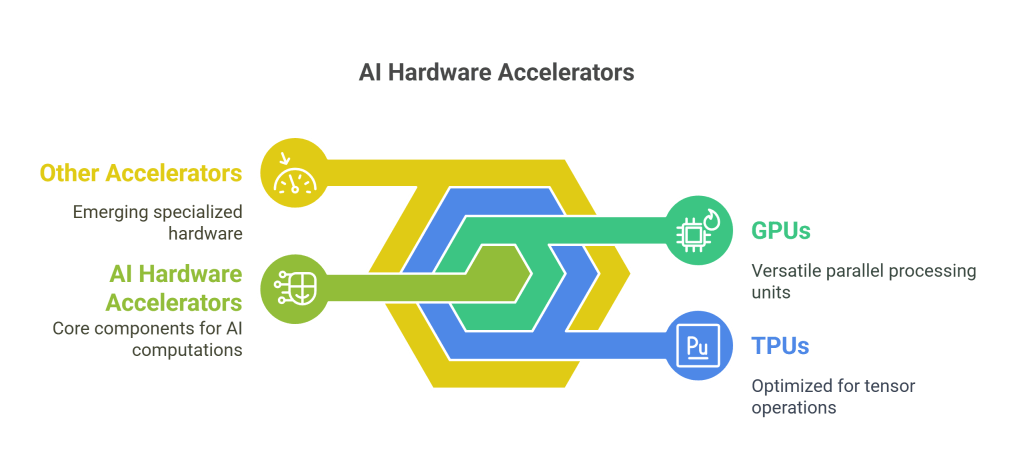

The Need for Specialized Hardware: Traditional CPUs (Central Processing Units), while versatile, are often insufficient for the massive parallel computations required by deep learning models. AI, particularly deep learning, heavily relies on matrix multiplications and tensor operations performed across vast datasets. This necessitates hardware specifically designed for parallelism.

- GPUs (Graphics Processing Units): Originally designed for rendering graphics, GPUs, particularly those from NVIDIA and AMD, have become the workhorses of AI. Their architecture, featuring thousands of smaller cores, is exceptionally well-suited for performing the same operation simultaneously on large blocks of data – the essence of deep learning computations. Libraries like NVIDIA’s CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) provide a programming model that allows developers to harness this parallel power for general-purpose computing, including AI training and inference.

- TPUs (Tensor Processing Units): Developed by Google, TPUs are Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) custom-built to accelerate machine learning workloads, specifically those using Google’s TensorFlow framework. They are highly optimized for tensor operations, offering significant performance and efficiency gains for specific types of large-scale training and inference tasks, particularly within Google Cloud’s ecosystem.

- Other Accelerators: The field is constantly evolving, with other specialized hardware emerging, such as FPGAs (Field-Programmable Gate Arrays) that can be reconfigured for specific tasks, and NPUs (Neural Processing Units) integrated into smartphones and other devices for efficient on-device AI.

Edge Devices: Not all AI computation happens in massive data centers. Edge AI involves running AI models directly on endpoint devices like smartphones, IoT sensors, cameras, drones, or even within vehicles. This requires hardware optimized for low power consumption, small form factors, and efficient inference capabilities. Companies are developing specialized System-on-Chips (SoCs) with integrated AI accelerators (NPUs) to enable powerful AI processing at the edge, reducing latency, enhancing privacy, and enabling operation without constant cloud connectivity.

Quantum Computing: While still largely experimental, quantum computing holds immense potential for the future of AI. Quantum computers leverage the principles of quantum mechanics (superposition and entanglement) to perform certain types of calculations exponentially faster than classical computers. This could revolutionize areas like optimization problems, materials science simulation, and specific types of machine learning algorithms, potentially unlocking breakthroughs currently intractable with existing hardware. However, building stable, scalable quantum computers remains a significant engineering challenge.

Infrastructure Considerations: Beyond the processors, the Physical Hardware Layer includes:

- Storage: AI models require vast amounts of data for training and storage for the models themselves. This necessitates high-capacity, high-speed storage solutions (like SSDs and distributed file systems) to ensure data can be accessed quickly during training and inference.

- Networking: High-bandwidth, low-latency networking is critical, especially in distributed AI setups where data and model parameters are exchanged between multiple machines or accelerators. Technologies like InfiniBand are often used in high-performance computing clusters for AI.

- Cooling and Power: The intense computations performed by AI hardware generate significant heat and consume substantial power. Data centers housing AI infrastructure require sophisticated cooling systems and robust power delivery to operate reliably.

In essence, the Physical Hardware Layer provides the indispensable physical resources. The choices made here – the type of accelerators, the scale of the infrastructure (cloud vs. on-premise vs. edge), and the supporting components – directly impact the performance, cost, scalability, and feasibility of any AI project. It is the silent, powerful engine driving the layers above.

Layer 2: The Data Link Layer – Bridging Models and Operations

Once AI models are trained (a process detailed in Layer 5), they need to be deployed, managed, and integrated into real-world applications or workflows. The Data Link Layer acts as this crucial bridge, encompassing the infrastructure, tools, and practices required to make AI models operational, accessible, and reliable. It’s where the theoretical model meets practical application, focusing on deployment, serving, orchestration, and ongoing management.

Model Serving: A trained model, often a large file containing parameters and architecture, needs to be loaded onto a server or device where it can receive input data and return predictions (inference). Model serving platforms are designed for this purpose, providing efficient and scalable ways to expose models as usable services.

- Tools: Frameworks like TensorFlow Serving, TorchServe (for PyTorch), NVIDIA Triton Inference Server, or custom solutions built using web frameworks like FastAPI or Flask are common. These tools handle loading models, managing versions, optimizing inference performance (e.g., through batching requests), and providing APIs (often REST or gRPC) for applications to interact with the model.

API Integration: Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are the standard way for different software components to communicate. In the Data Link Layer, APIs expose the functionality of the deployed AI model. Applications can send data (e.g., text for translation, an image for classification) to the model’s API endpoint and receive the AI-generated output. This abstraction allows developers to integrate AI capabilities into their applications without needing deep knowledge of the underlying model architecture or hardware.

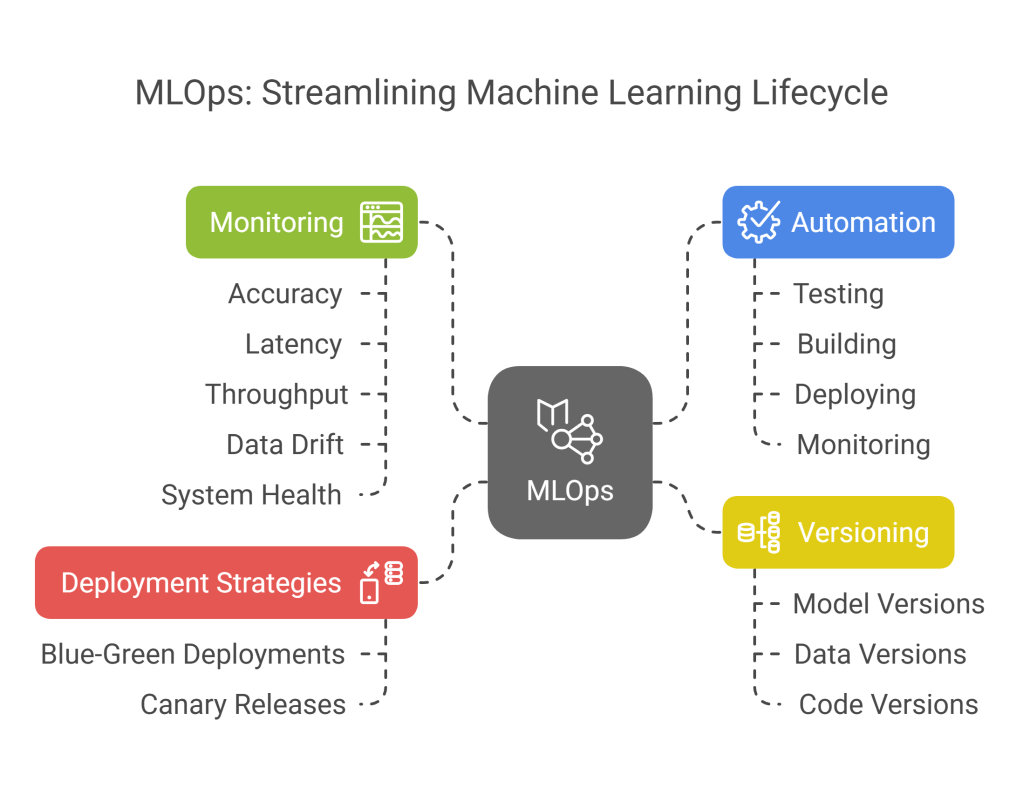

MLOps (Machine Learning Operations): Drawing inspiration from DevOps in software engineering, MLOps focuses on streamlining the lifecycle of machine learning models, from development and training to deployment and monitoring. It emphasizes automation, collaboration, and reproducibility. Key aspects handled at this layer include:

- Deployment Strategies: Implementing strategies like blue-green deployments or canary releases to safely roll out new model versions.

- Monitoring: Continuously tracking model performance (accuracy, latency, throughput), data drift (changes in input data characteristics), and system health.

- Versioning: Managing different versions of models, data, and code to ensure reproducibility and traceability.

- Automation: Automating the processes of testing, building, deploying, and monitoring models using CI/CD (Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment) pipelines adapted for ML.

AI Orchestration: Modern AI applications often involve complex workflows combining multiple AI models, data sources, and traditional software components. AI orchestration tools help manage these intricate sequences.

- Tools: Frameworks like LangChain, LlamaIndex, or AutoGPT (and similar agent-based systems) provide structures for chaining calls to different models (especially Large Language Models – LLMs), retrieving data, interacting with external tools via APIs, and managing the flow of information. They enable the creation of sophisticated applications like AI agents that can perform multi-step tasks, reason over data, and interact with various services.

Scalability, Availability, and Security: Ensuring that the deployed AI services can handle varying loads (scalability), remain operational without interruption (availability), and are protected from unauthorized access or attacks (security) is paramount. This involves using load balancers, auto-scaling mechanisms (common in cloud platforms), redundant deployments, robust authentication/authorization protocols, and monitoring for potential security threats targeting the AI models or infrastructure.

Examples in Practice: The Data Link Layer manifests in various ways:

In summary, the Data Link Layer is the operational backbone of applied AI. It takes the trained intelligence from the Learning Layer and makes it reliably and efficiently available to the Application Layer, handling the critical engineering challenges of deployment, integration, management, and scaling.

Layer 3: The Computation Layer – The Engine of Inference and Execution

While the Physical Hardware Layer provides the raw power, and the Data Link Layer manages deployment, the Computation Layer is where the AI model actively thinks and acts during runtime (inference). This layer is responsible for the real-time processing of input data, executing the model’s logical steps, and generating outputs or predictions. It leverages the underlying hardware and frameworks to perform these computations efficiently and quickly.

Inference: This is the primary task of the Computation Layer in a deployed system. Inference is the process of using a trained AI model to make predictions on new, unseen data. Unlike training, which involves adjusting model parameters based on large datasets, inference focuses on applying the learned patterns. For example:

- Feeding an image to a trained object detection model to get bounding boxes around detected objects.

- Providing a sentence to a language translation model to get its translation.

- Inputting sensor data into a predictive maintenance model to estimate the likelihood of equipment failure.

Real-Time Processing: Many AI applications require immediate responses. Think of autonomous vehicles needing to react instantly to obstacles, voice assistants responding conversationally, or fraud detection systems flagging suspicious transactions in milliseconds. The Computation Layer must be optimized for low latency, ensuring that the processing from input to output happens within the required time constraints. This often involves techniques like model quantization (reducing model size and precision for faster computation), hardware acceleration, and efficient data handling.

Logical Execution: AI models, especially complex ones like deep neural networks, involve a sequence of mathematical operations (matrix multiplications, activation functions, etc.) applied layer by layer. The Computation Layer executes this predefined logical flow. For frameworks like TensorFlow or PyTorch, this involves executing the computational graph defined by the model architecture. For simpler models like decision trees, it involves traversing the tree based on the input data.

Leveraging AI Accelerators: This layer directly interfaces with and utilizes the specialized hardware from Layer 1 (GPUs, TPUs, NPUs). AI frameworks (like TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX) provide high-level APIs for defining models, but their backend execution engines are optimized to translate these definitions into low-level instructions that run efficiently on the available accelerators. This ensures that the computationally intensive parts of the model run as fast as possible.

Distributed Computing: For very large models or high-throughput applications, inference might need to be distributed across multiple machines or devices. The Computation Layer handles aspects of this distribution:

- Model Parallelism: Splitting a single large model across multiple accelerators.

- Data Parallelism: Processing different batches of input data simultaneously on multiple replicas of the model.

- Pipeline Parallelism: Breaking the model’s layers into stages and processing data sequentially through these stages distributed across different accelerators.Frameworks and serving platforms often provide mechanisms to manage this distribution.

Edge AI Computation: When models run on edge devices (Layer 1), the Computation Layer operates within the constraints of that device (limited power, memory, processing capability). This necessitates highly optimized models and efficient runtime engines (like TensorFlow Lite, PyTorch Mobile, ONNX Runtime) designed specifically for edge environments. Computation might involve leveraging dedicated NPUs on the device for acceleration.

Federated Learning: This is a specific distributed computing paradigm where model training (Layer 5) and potentially inference happen on decentralized devices (like smartphones) without the raw data leaving the device. The Computation Layer on each device performs local computations, and only model updates (not raw data) are aggregated centrally. This preserves user privacy while still allowing collaborative model improvement.

AI Frameworks (Runtime Role): While frameworks like PyTorch, TensorFlow, and JAX are crucial for training (Layer 5), they also play a vital role in the Computation Layer during inference. They provide the runtime environment that loads the trained model, interprets its structure, and executes the necessary computations on the target hardware (CPU, GPU, TPU, etc.). They manage memory allocation, schedule operations, and optimize the execution flow.

Examples:

- A language model running inference on a GPU cluster in the cloud, processing thousands of user queries per second via an API (managed by Layer 2).

- An object detection model running on an NPU within a smart camera, analyzing the video feed in real-time.

- A recommendation engine executing its algorithm within a distributed system to generate personalized suggestions for users on a streaming platform.

- A federated learning setup where keyboard prediction models on millions of smartphones perform local inference and computation for updates.

The Computation Layer is the dynamic heart of a running AI system. It translates the static, trained model into active predictions and decisions, efficiently managing the flow of data and calculations, whether in a powerful data center or on a resource-constrained edge device.

Layer 4: The Knowledge Layer – Augmenting AI with External Information

Standard AI models, even powerful ones like LLMs, are typically trained on a fixed dataset. Their knowledge is limited to the information present in that data up to the point of training. They can struggle with tasks requiring real-time information, domain-specific knowledge not covered in the training data, or complex reasoning that goes beyond pattern matching. The Knowledge Layer addresses these limitations by providing mechanisms for AI models to access, retrieve, and reason over external information sources, significantly enhancing their capabilities, accuracy, and relevance.

The Need for External Knowledge:

- Timeliness: Models trained on past data don’t know about recent events.

- Specificity: General models may lack deep knowledge of niche domains (e.g., specific legal cases, complex medical conditions, internal company documentation).

- Fact-Checking: Generative models can sometimes “hallucinate” or produce plausible but incorrect information. Accessing authoritative sources can mitigate this.

- Complex Reasoning: Solving problems often requires combining information from multiple sources or performing logical deductions based on retrieved facts.

Key Technologies and Techniques:

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): This has become a prominent technique, especially for LLMs. RAG combines the generative power of a pre-trained model with an information retrieval component. When presented with a query or prompt:

- Retrieval: The system first searches a relevant external knowledge corpus (e.g., a set of documents, a database, web search results) to find information related to the query.

- Augmentation: The retrieved information is then added to the original prompt as context.

- Generation: The LLM uses both the original prompt and the retrieved context to generate a more informed, accurate, and contextually relevant response.This allows LLMs to incorporate up-to-date information or domain-specific knowledge without needing retraining.

- Knowledge Graphs (KGs): KGs represent information as a network of entities (nodes) and relationships (edges). They provide a structured way to store factual knowledge (e.g., “Paris” -is located in-> “France”; “Marie Curie” -won-> “Nobel Prize”). AI models can query these graphs to retrieve specific facts, understand relationships between entities, and perform more complex reasoning tasks. KGs can be built from structured data or extracted from unstructured text.

- Vector Search and Vector Databases: This technique is often the core of the retrieval step in RAG. It involves converting both the query and the documents in the knowledge corpus into numerical representations called embeddings (vectors) – a process often handled by the Representation Layer (Layer 6). Vector databases (e.g., Pinecone, Weaviate, Milvus, Chroma) are specialized databases designed to efficiently store and search these high-dimensional vectors. When a query comes in, its vector is compared against the vectors in the database to find the most semantically similar (and therefore relevant) pieces of information using algorithms like Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search.

- Reasoning Engines: Beyond simple retrieval, some systems incorporate explicit reasoning engines. These might use logical rules (like symbolic AI approaches) or leverage the implicit reasoning capabilities of large models, guided by retrieved knowledge, to perform multi-step deductions, check consistency, or synthesize information from multiple sources.

Enhancing AI Capabilities: The Knowledge Layer significantly boosts AI performance:

- Improved Accuracy: Grounding responses in factual, retrieved data reduces hallucinations and improves the reliability of generative models.

- Enhanced Relevance: Accessing specific, up-to-date information makes AI outputs more relevant to the user’s current context or query.

- Domain Adaptation: Allows general models to perform well in specialized domains by providing access to relevant domain knowledge bases.

- Transparency and Explainability: In some RAG systems, the AI can cite the sources it used for retrieval, providing users with transparency and the ability to verify the information.

Examples:

- Search Engines: Modern search engines often use LLMs augmented with real-time web search results (RAG) to provide direct answers and summaries.

- AI Assistants: Chatbots or assistants that can answer questions about recent news, access company-specific documents, or provide information from curated databases.

- Code Generation: Tools like GitHub Copilot implicitly leverage vast amounts of code and documentation, acting like a knowledge base to suggest relevant code snippets.

- Semantic Search: Enterprise search systems that use vector search over internal documents to find information based on meaning rather than just keywords.

The Knowledge Layer acts as the AI’s external brain or library. By integrating mechanisms for retrieval and reasoning over external data sources, it transforms AI models from static pattern recognizers into dynamic, informed systems capable of tackling a wider range of tasks with greater accuracy and relevance.

Layer 5: The Learning Layer – The Heart of Model Training and Optimization

This layer is where the “intelligence” of the AI model is forged. The Learning Layer encompasses the core machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, training processes, and optimization techniques used to teach models patterns, relationships, and decision-making capabilities from data. It’s arguably the most defining layer, as the choices made here determine the fundamental abilities and limitations of the resulting AI.

Core Concepts:

- Machine Learning Paradigms:

- Supervised Learning: The most common paradigm, where the model learns from labeled data (input-output pairs). It learns a mapping function to predict outputs for new inputs. Examples include classification (predicting categories, e.g., spam detection) and regression (predicting continuous values, e.g., house price prediction).

- Unsupervised Learning: The model learns from unlabeled data, identifying patterns, structures, or relationships inherent in the data itself. Examples include clustering (grouping similar data points, e.g., customer segmentation) and dimensionality reduction (simplifying data while preserving important information, e.g., PCA).

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): The model (agent) learns by interacting with an environment. It receives rewards or penalties for its actions and learns a policy (a strategy) to maximize cumulative rewards over time. Used extensively in robotics, game playing (AlphaGo), and optimization problems.

Model Architectures: This layer involves selecting or designing the appropriate model structure for the task:

- Neural Networks (NNs): Inspired by the structure of the brain, NNs consist of interconnected nodes (neurons) organized in layers. They are the foundation of deep learning.

- Deep Learning (DL): A subfield of ML focusing on NNs with many layers (deep architectures). Key DL architectures include:

- Transformers: Revolutionized natural language processing (NLP). They use a mechanism called “self-attention” to weigh the importance of different words in an input sequence, enabling models like GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), BERT, and T5 to achieve state-of-the-art performance on various language tasks.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Highly effective for processing grid-like data, particularly images. They use convolutional layers to automatically learn spatial hierarchies of features (edges, textures, shapes). Dominant in computer vision tasks like image classification, object detection, and segmentation.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Designed for sequential data (text, time series). They have connections that form cycles, allowing information to persist (“memory”). Variants like LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory) and GRUs (Gated Recurrent Units) address challenges in learning long-range dependencies. While powerful, Transformers have surpassed RNNs in many sequence tasks.

- Traditional ML Models: Simpler but often effective models like Decision Trees, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and linear/logistic regression are also part of this layer, particularly useful for structured data and when interpretability is crucial.

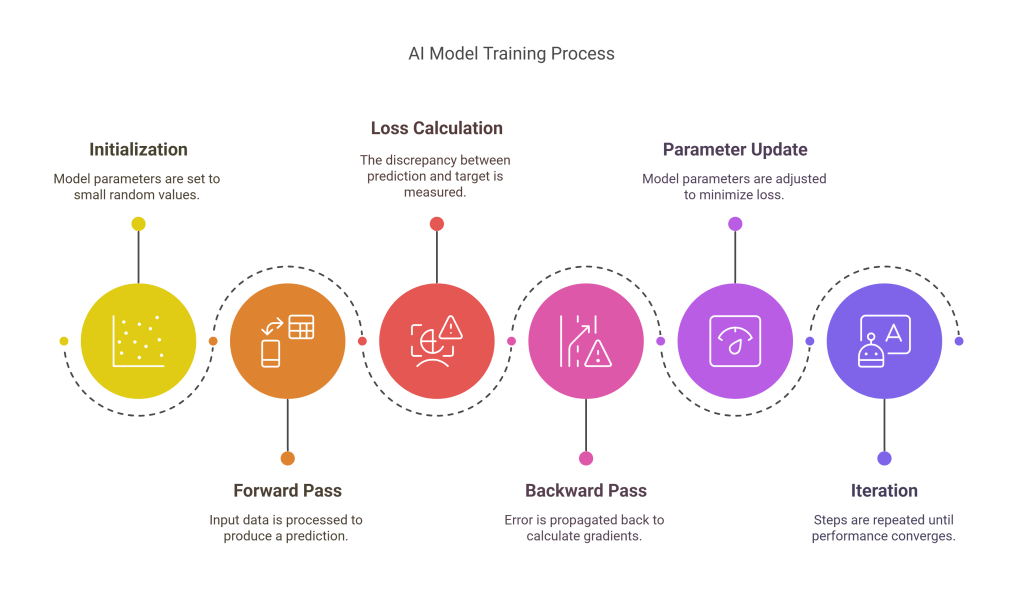

The Training Process:

- Initialization: Model parameters (weights and biases) are typically initialized with small random values.

- Forward Pass: Input data is fed through the model architecture to produce an initial prediction or output.

- Loss Calculation: A loss function (or cost function) measures the discrepancy between the model’s prediction and the actual target value (in supervised learning) or evaluates a specific objective (in unsupervised or reinforcement learning). Examples include Mean Squared Error (for regression) and Cross-Entropy Loss (for classification).

- Backward Pass (Backpropagation): For neural networks, the error is propagated backward through the network layers. Calculus (specifically, the chain rule) is used to calculate the gradient (derivative) of the loss function with respect to each model parameter. This gradient indicates how much a small change in each parameter would affect the error.

- Parameter Update (Optimization): An optimization algorithm uses the calculated gradients to update the model parameters in a direction that minimizes the loss function.

- Gradient Descent: The most fundamental optimizer. It iteratively adjusts parameters in the opposite direction of the gradient.

- Variants: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Mini-batch Gradient Descent, Adam, RMSprop are more sophisticated optimizers commonly used in deep learning for faster and more stable convergence.

- Iteration: Steps 2-5 are repeated many times (epochs) over the training dataset until the model’s performance converges or reaches a satisfactory level on a separate validation dataset.

Reinforcement Learning Specifics: RL training involves the agent exploring the environment, taking actions, receiving rewards/penalties, and updating its policy using algorithms like Q-learning, SARSA, or policy gradient methods (e.g., PPO, TRPO) to learn optimal behavior.

Examples:

- Training a GPT model: Using a massive text corpus, a Transformer architecture, and optimization techniques like Adam to learn language patterns for generation.

- Computer Vision: Training a CNN on millions of labeled images (using backpropagation and gradient descent) to recognize objects.

- Autonomous Driving: Using reinforcement learning to train an agent to navigate complex traffic scenarios by rewarding safe and efficient driving actions.

- Fraud Detection: Training a gradient boosting model on historical transaction data (labeled as fraudulent or not) to predict the likelihood of fraud for new transactions.

The Learning Layer is where raw potential (data and architecture) is transformed into learned capability through rigorous training and optimization. The effectiveness of the algorithms, the quality and quantity of data, and the computational resources available for training are all critical factors determining the success of the final AI model.

Layer 6: The Representation Layer – Shaping Data for AI Understanding

AI models, particularly complex neural networks, don’t understand data in its raw, human-readable format (like text, images, or sound waves). They operate on numerical data, typically vectors or tensors (multi-dimensional arrays). The Representation Layer is responsible for the critical process of transforming raw input data into these meaningful numerical representations that AI models can ingest and learn from effectively. This involves data preprocessing, feature engineering, and generating embeddings.

The Importance of Representation: The quality of the input representation directly impacts a model’s ability to learn patterns and make accurate predictions. Poorly represented data can hide important signals or introduce noise, hindering the learning process. Good representations make the underlying patterns more apparent and easier for the model to capture.

Key Processes:

- Data Preprocessing: Cleaning and preparing raw data before feature extraction. This includes:

- Handling Missing Values: Imputing missing data points using techniques like mean/median substitution or more sophisticated methods.

- Cleaning: Removing errors, outliers, or inconsistencies.

- Normalization/Standardization: Scaling numerical features to a common range (e.g., 0 to 1 or with zero mean and unit variance). This prevents features with larger values from disproportionately influencing the model and helps optimization algorithms converge faster.

- Feature Engineering: The art and science of creating new input features from existing raw data to better represent the underlying problem for the model. This often requires domain expertise. Examples include:

- Creating interaction terms (e.g., multiplying two features).

- Extracting components from dates (e.g., day of the week, month).

- Calculating ratios or aggregations.

- For text, creating features like sentence length or sentiment score.While deep learning models can learn features automatically to some extent, explicit feature engineering is still crucial, especially for tabular data and traditional ML models.

- Data Type Specific Transformations:

- Text Data:

- Tokenization: Breaking text down into smaller units (words, subwords, or characters) called tokens.

- Vectorization: Converting tokens into numerical vectors.

- Bag-of-Words (BoW): Representing text by the frequency of words (e.g., TF-IDF, CountVectorizer). Ignores word order.

- Embeddings: Dense vector representations that capture semantic meaning. Words or sentences with similar meanings have similar vectors. Techniques include Word2Vec, GloVe, FastText, and more advanced contextual embeddings from models like BERT, RoBERTa, or Sentence-Transformers. These embeddings are often pre-trained on large corpora and can be fine-tuned for specific tasks.

- Image Data: Images are typically represented as grids of pixel values (e.g., 3D tensors for color images: height x width x color channels). Preprocessing might involve resizing, normalization of pixel values, and data augmentation (e.g., rotations, flips) to increase dataset diversity.

- Audio Data: Raw audio waveforms are often converted into spectrograms (visual representations of frequency content over time) using techniques like the Fourier Transform (specifically, Short-Time Fourier Transform – STFT). These spectrograms can then be treated similarly to images and fed into CNNs.

- Categorical Data: Non-numerical features (e.g., ‘color’: ‘red’, ‘blue’, ‘green’) need conversion. Techniques include:

- One-Hot Encoding: Creating binary columns for each category.

- Label Encoding: Assigning a unique integer to each category (use with caution as it implies an ordinal relationship).

- Embedding Layers: Learning dense vector representations for categories, similar to word embeddings (often used within neural networks).

- Text Data:

The Role of Embeddings: Embeddings are a cornerstone of modern AI representation, especially for unstructured data like text and sometimes images or categorical features. They map discrete items (words, pixels, categories) into a continuous vector space where semantic similarity often translates to spatial proximity. This allows models to generalize better and understand relationships between different inputs. These embeddings can be pre-trained (Layer 5) or learned as part of the main model training process.

Examples:

- NLP: Converting a user’s text query “best italian restaurants near me” into a sequence of dense vectors (embeddings) that capture the meaning and intent, ready to be fed into an LLM or a search algorithm.

- Computer Vision: Transforming a digital photograph into a normalized 3D array of pixel values (e.g., 224x224x3) as input for a CNN like ResNet.

- Recommendation Systems: Creating vector embeddings for users and items (e.g., movies, products) based on their past interactions. Recommendations are made by finding items whose embeddings are close to the user’s embedding in the vector space.

- Time Series Analysis: Applying Fourier transforms to sensor data to extract frequency components as features for a predictive maintenance model.

The Representation Layer is a critical preparatory stage. It translates the diverse language of raw data into the uniform numerical language that AI models understand. The techniques employed here – from simple normalization to sophisticated learned embeddings – lay the groundwork for successful learning in the subsequent layer.

Layer 7: The Application Layer – The AI Interface and Deployment

The culmination of all the preceding layers is the Application Layer. This is the final frontier where the AI system interacts with the end-user, another software system, or the real world. It represents the tangible output or service enabled by the underlying AI model and infrastructure. This layer focuses on delivering the AI’s capabilities in a usable, accessible, and often user-friendly manner.

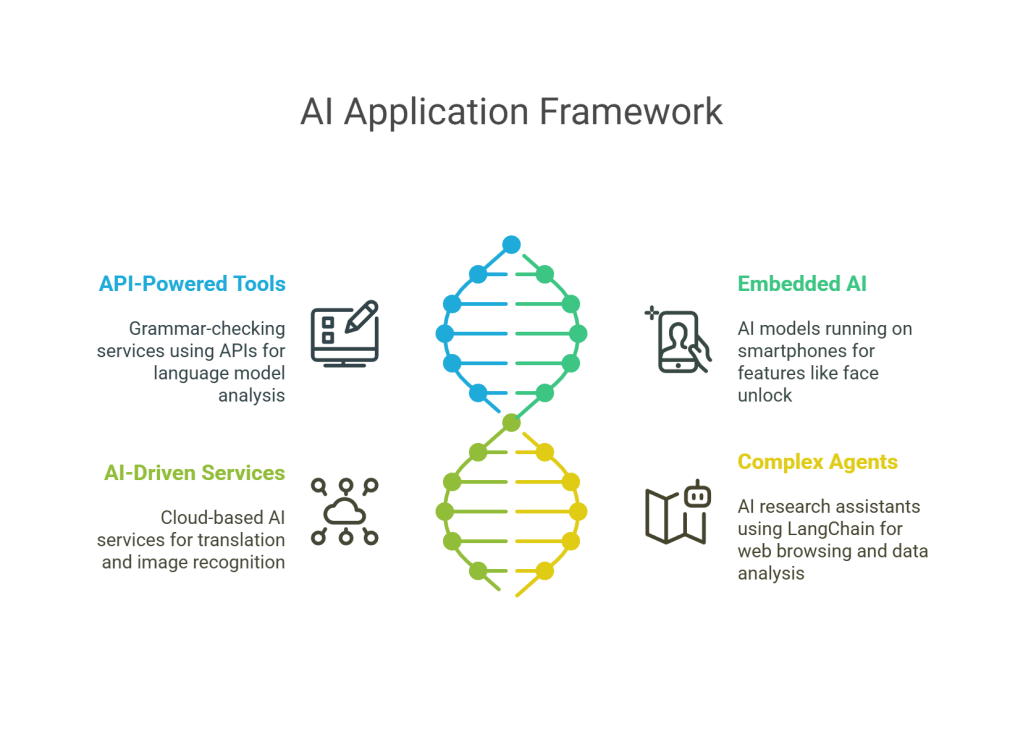

Forms of Interaction: The Application Layer can take many forms, depending on the AI’s purpose and intended audience:

- Chatbots and Conversational AI: Interfaces allowing users to interact with AI using natural language (text or voice). Examples include customer service bots, virtual assistants (like Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant), and interactive information retrieval systems. LLM-powered applications like ChatGPT, Bard, and Claude are prime examples operating at this layer.

- AI Assistants: Tools designed to help users perform tasks more efficiently. This could range from grammar correction software and code completion tools (like GitHub Copilot) to more complex AI agents capable of planning and executing multi-step actions based on user goals.

- Automation Tools: AI integrated into workflows to automate repetitive or complex tasks. Examples include robotic process automation (RPA) enhanced with AI for decision-making, automated content generation tools, or AI-powered data analysis platforms.

- APIs for Developers: Exposing AI functionality (e.g., image recognition, translation, sentiment analysis) as an API allows other developers to integrate these capabilities into their own applications without building the models themselves. Cloud providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure) offer numerous such AI services.

- Embedded AI Features: AI capabilities seamlessly integrated into existing software or hardware products. Examples include recommendation engines on streaming platforms, predictive text on smartphone keyboards, spam filters in email clients, or driver-assistance features in cars.

- Robotics and Physical Systems: For AI controlling robots or physical systems (like autonomous vehicles or industrial robots), the Application Layer involves the control systems that translate AI decisions into physical actions and the sensors providing real-world feedback.

User Experience (UX) and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI): For user-facing applications, the design of the interface and the interaction model are critical. A powerful AI model is useless if users cannot easily access or understand its output. This layer involves:

- Interface Design: Creating intuitive graphical user interfaces (GUIs), command-line interfaces (CLIs), or voice user interfaces (VUIs).

- Presenting Results: Displaying AI outputs (predictions, classifications, generated content) in a clear, understandable, and actionable way. This might involve visualizations, confidence scores, or explanations.

- Handling Uncertainty: Communicating the model’s confidence or potential limitations to the user.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Allowing users to provide feedback on the AI’s performance, which can be used for continuous improvement (potentially feeding back into Layer 5).

Integration with Business Logic: AI models rarely operate in isolation. The Application Layer often involves integrating the AI component with broader business logic, databases, user authentication systems, and other parts of a larger software application.

Deployment Context: The nature of the Application Layer is also influenced by the deployment context determined in Layer 2:

- Web Applications: AI features accessed through a web browser.

- Mobile Apps: AI running on or accessed by a mobile application.

- Desktop Software: AI integrated into traditional desktop programs.

- Backend Services: AI providing functionality consumed by other services without a direct user interface.

Examples:

- ChatGPT Interface: The web-based chat interface allowing users to type prompts and receive text responses from the underlying LLM.

- Netflix Recommendation Rows: The UI elements displaying personalized movie and TV show suggestions generated by the recommendation engine.

- Tesla Autopilot: The driver-assistance system using AI models (trained in Layer 5, running in Layer 3 on edge hardware from Layer 1) to perceive the environment and control the vehicle, with information presented to the driver via the car’s display.

- Google Translate App: The mobile application providing an interface for users to input text or speech and receive translations generated by Google’s translation models.

The Application Layer is where the value of the AI system is ultimately realized. It bridges the gap between complex internal workings and practical utility, packaging the AI’s intelligence into a form that solves problems, provides insights, entertains, or assists users and systems in the real world.

Interconnections and the Flow Through Layers

While presented as distinct layers, the reality of AI architecture involves intricate interconnections and a continuous flow of data and control between them. During the training phase, the flow typically moves upwards: Raw data is collected, processed and transformed in the Representation Layer (6), fed into the chosen model architecture in the Learning Layer (5) which utilizes the Computation Layer (3) and underlying Physical Hardware (1) for intensive calculations and optimization.

During the inference or deployment phase, the flow often starts at the top and moves down and back up: A user interacts with the Application Layer (7), sending a request. This request might be routed via the Data Link Layer (2) to the appropriate model serving instance. The input data within the request is processed by the Representation Layer (6) into a numerical format. The Computation Layer (3), running on the Physical Hardware (1), executes the trained model (from Layer 5) using this representation to generate a prediction. This prediction might be enhanced or validated by accessing external information via the Knowledge Layer (4). The final output is then passed back up through the Data Link Layer (2) to the Application Layer (7) to be presented to the user or consumed by another system. MLOps practices within the Data Link Layer (2) continuously monitor this entire inference process.

This layered structure provides modularity. Improvements or changes in one layer (e.g., upgrading hardware in Layer 1, refining the model architecture in Layer 5, improving the UI in Layer 7) can often be made without completely overhauling the entire system, although dependencies certainly exist.

Conclusion: Building Intelligence, Layer by Layer

The journey from a concept to a fully functional, deployed AI system is a complex, multi-faceted process. Conceptualizing this journey through a layered architecture, such as the seven layers discussed – Physical Hardware, Data Link, Computation, Knowledge, Learning, Representation, and Application – provides an invaluable framework for understanding the constituent parts and their interactions.

Each layer addresses specific challenges and utilizes distinct technologies and methodologies. The Physical Hardware provides the essential computational power. The Representation Layer translates raw data into a language models understand. The Learning Layer imbues the model with intelligence through training and optimization. The Knowledge Layer enhances reasoning and factual grounding. The Computation Layer executes the model efficiently during inference. The Data Link Layer manages deployment, scaling, and operational concerns. Finally, the Application Layer delivers the AI’s capabilities to the end-user or system.

This layered perspective highlights that building successful AI is not just about sophisticated algorithms (Layer 5) but requires a holistic approach encompassing robust infrastructure (Layer 1), efficient data handling (Layer 6), operational excellence (Layer 2), effective computation (Layer 3), potential knowledge integration (Layer 4), and user-centric delivery (Layer 7). As AI continues to evolve, the technologies and techniques within each layer will undoubtedly advance, but the fundamental principle of breaking down complexity into manageable, interconnected components will remain a cornerstone of building powerful and reliable artificial intelligence systems. Understanding these layers empowers developers, researchers, and decision-makers to navigate the complexities of AI development and harness its transformative potential effectively.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.