In a world increasingly defined by specialization and routine, the ability to remain genuinely curious stands as perhaps our most valuable intellectual asset. Curiosity—that innate desire to explore, question, and understand—fuels innovation, deepens relationships, and enriches our daily experience. Yet for many of us, curiosity has become a casualty of busy schedules, information overload, and educational systems that reward knowing answers more than asking insightful questions.

The good news is that curiosity isn’t simply an inborn trait that some possess and others lack. Rather, it’s a capacity that can be deliberately cultivated, expanded, and refined throughout our lives. This article explores the art and science of nurturing curiosity and using it to challenge ourselves in increasingly meaningful ways. Whether you’re looking to reignite your sense of wonder, break through professional plateaus, or simply enrich your daily experience, the path begins with understanding and developing your curious mind.

Understanding Curiosity: More Than Just Wanting to Know

Curiosity isn’t a single impulse but rather a complex set of motivations and behaviors that drive exploration and learning. Psychologists distinguish between several forms of curiosity, each serving different purposes in our intellectual and emotional lives:

Epistemic curiosity represents our desire for knowledge and understanding. It’s what drives us to research topics, solve puzzles, and develop expertise. This form of curiosity tends to be self-reinforcing—the more we learn, the more connections we see, and the more curious we become.

Perceptual curiosity is triggered by novel, puzzling, or ambiguous stimuli in our environment. It’s what makes us turn our head at an unusual sound or explore an unfamiliar neighborhood. This form of curiosity helps us adapt to and understand our surroundings.

Specific curiosity focuses on filling particular knowledge gaps or resolving discrete questions. It’s what drives us to look up an unfamiliar word or figure out how a mechanism works.

Diversive curiosity represents our general seeking of novelty and variety to combat boredom or stagnation. It’s what might lead us to browse random topics online or pick up a magazine on an unfamiliar subject.

The distinction matters because different situations may call for different types of curiosity. Professional growth might require deep epistemic curiosity in your field, while preventing creative burnout might depend on nurturing diversive curiosity through varied experiences.

Recent neuroscience research has shown that curiosity does more than simply motivate learning—it actually primes the brain for it. When we’re curious, the brain releases dopamine and activates the hippocampus, enhancing our ability to remember what we learn. This creates a virtuous cycle: curiosity makes learning more rewarding, which in turn fuels more curiosity.

The Barriers to Curiosity in Modern Life

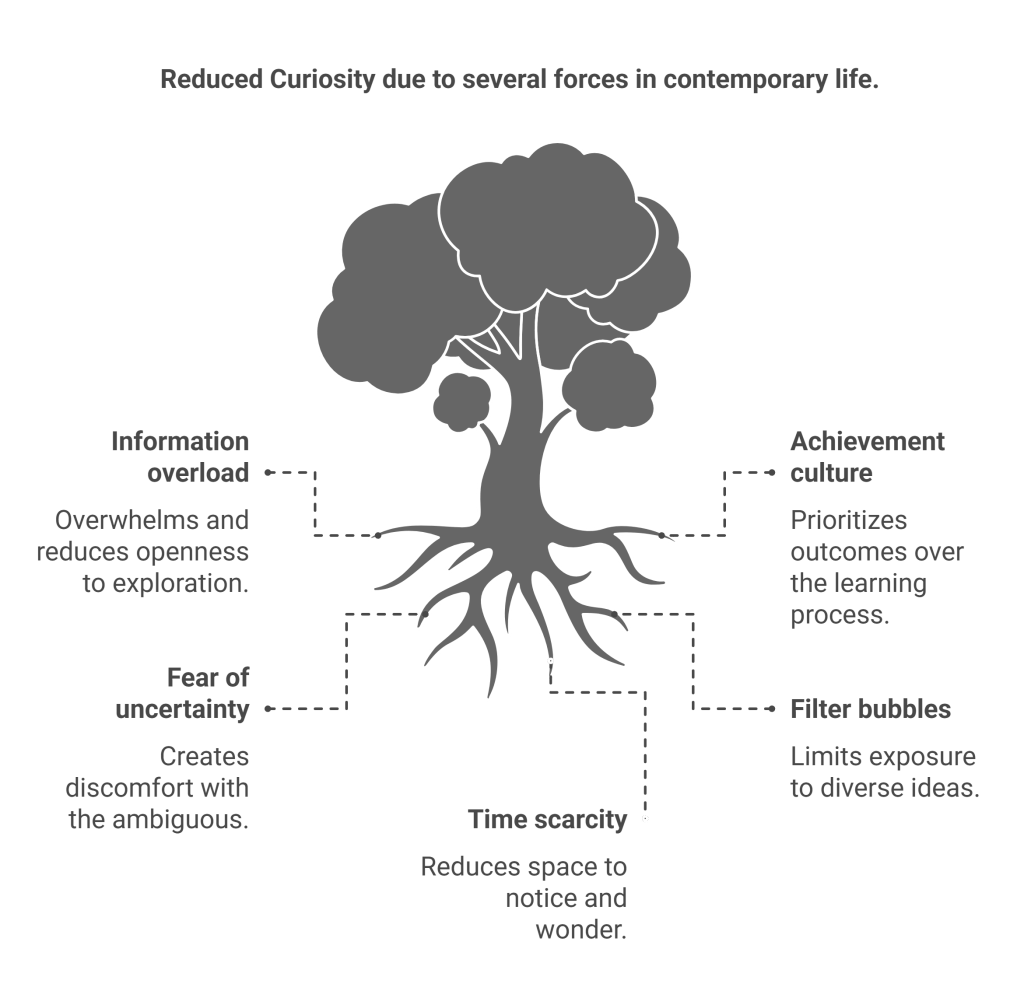

Before exploring how to cultivate curiosity, it’s worth examining what stands in its way. Despite our natural capacity for wonder, several forces in contemporary life can dampen our curiosity:

Information overload can paradoxically reduce curiosity by overwhelming us. When we’re flooded with facts, notifications, and updates, we tend to retreat to familiar territory rather than remaining open to exploration.

Achievement culture often prioritizes outcomes (grades, metrics, credentials) over the learning process itself. This can train us to value being right more than being inquisitive.

Fear of uncertainty inhibits curiosity by making us uncomfortable with the ambiguous, messy territory that curiosity often leads us into. In a world that rewards certainty and quick answers, the vulnerability of “not knowing” can feel threatening.

Filter bubbles limit our exposure to diverse ideas and perspectives, narrowing the range of what we might become curious about. When algorithms feed us more of what we already know and like, our curiosity naturally narrows.

Time scarcity may be the most significant barrier. Curiosity requires space—mental and temporal—to notice, wonder, and follow threads of interest. When every minute is scheduled and optimized, curiosity struggles to find footing.

Recognizing these barriers is the first step toward dismantling them. The practices that follow are designed not just to stimulate curiosity but to create the conditions where it can naturally flourish.

Cultivating Curiosity: Practical Strategies and Examples

1. Mastering the Art of Questioning

Questions are the primary tools of curiosity, yet most of us have never been explicitly taught how to ask good ones. Effective questioning is a skill that can be developed with practice:

The Five Whys Technique originated in Toyota’s manufacturing process but works remarkably well for personal exploration. When facing any situation, decision, or problem, ask “why?” five times in succession to drill down to deeper understanding:

Example:

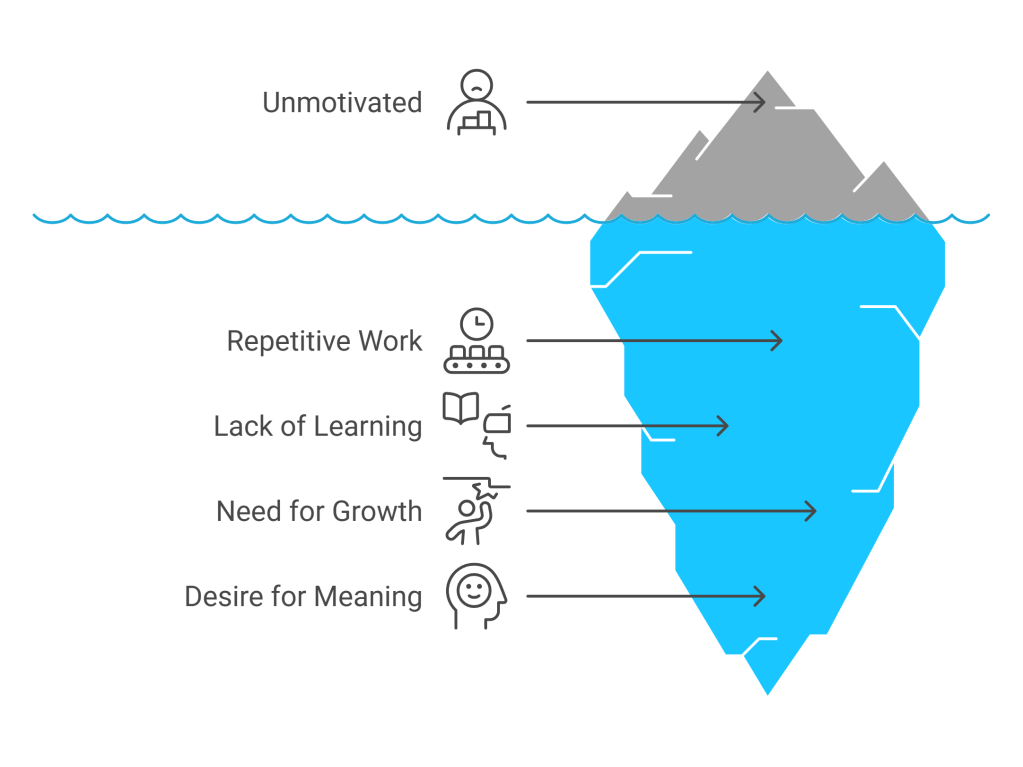

- “I’m feeling unmotivated at work.”

- Why? “My projects feel repetitive.”

- Why? “I’ve been doing the same type of work for two years.”

- Why is that a problem? “I’m not learning anything new.”

- Why is learning important? “Growth keeps me engaged.”

- Why does engagement matter? “Because I want work that feels meaningful.”

This simple practice reveals that the core issue isn’t motivation but a need for new challenges and learning opportunities—a much more actionable insight.

Question Framing significantly impacts the depth of exploration. Compare:

- “Do you like your job?” (closed, likely yields yes/no)

- “What aspects of your work do you find most energizing?” (open, invites reflection)

- “If you could redesign your role, what would you change?” (hypothetical, encourages creative thinking)

Socratic Questioning Framework provides a systematic approach to deeper inquiry through six question types:

- Clarification questions probe for details: “What exactly do you mean by ‘innovative approach’?”

- Assumption questions examine underlying beliefs: “What are we assuming about customer behavior here?”

- Evidence questions explore the basis for conclusions: “What observations led you to that conclusion?”

- Viewpoint questions consider alternative perspectives: “How might our competitors view this situation?”

- Implication questions look at consequences: “If this trend continues, what might happen next year?”

- Reflexive questions examine the question itself: “Why might this question be important to explore?”

The Naive Expert Technique combines the freshness of beginner’s questions with the insight of expertise. In any familiar situation, deliberately toggle between questions that come from complete naivety (“If I knew nothing about this, what would I ask?”) and deep expertise (“Given what we know, what subtle patterns might we be missing?”).

2. Creating a Curiosity-Friendly Environment

Our surroundings profoundly influence our capacity for curiosity. Consider these approaches to creating spaces—physical and mental—that nurture wonder:

The Curiosity Journal serves as both stimulus and record of your questioning mind. Unlike standard journaling, a curiosity journal focuses specifically on:

- Questions that arose during your day

- Assumptions you noticed and might question

- Unexpected observations or surprises

- Connections between seemingly unrelated ideas

- Topics you want to explore further

Example entry: “Noticed how the late afternoon light created different shadows than morning light. Why do we respond emotionally to certain qualities of light? Connection to seasonal affective disorder? Also: what determines leaf color beyond chlorophyll?”

The Curiosity Walk transforms routine environments into exploration spaces. Take 15-30 minutes in a familiar setting with the sole intention of noticing what you typically overlook. The key is to focus on observation without immediate judgment or categorization.

Example: “Walked my usual route to work but noticed the variance in brick patterns on buildings I pass daily. Some buildings use a stacked bond pattern while others use running bond. Why these choices? Also noticed how pedestrian behavior changes near intersections—people begin positioning themselves strategically about 15 feet before crosswalks.”

Input Diversity might be the single most important environmental factor for curiosity. We cannot be curious about what we’ve never encountered. Deliberately varying your information diet creates more opportunities for curiosity to spark:

- Follow people from different fields, backgrounds, and viewpoints

- Rotate between different types of reading (technical, narrative, philosophical)

- Explore cultural products from unfamiliar traditions and perspectives

- Engage with both contemporary ideas and historical contexts

Physical Cues can serve as tangible reminders to remain curious. Some professionals keep an empty chair in meeting rooms to represent an absent perspective. Others place objects on their desk that prompt questions or use visual cues like question marks in their environment.

3. The Question Toolkit: Teaching Others to Ask Better Questions

Whether you’re a parent, educator, manager, or simply someone interested in fostering more curious conversations, these techniques can help others develop stronger questioning habits:

Question Storming inverts the familiar brainstorming process. Instead of generating answers or solutions, the group focuses exclusively on producing questions about a topic or challenge. The rules are simple:

- Only questions are allowed (no hidden statements disguised as questions)

- No preambles or justifications

- No evaluation of questions during the generation phase

- Aim for quantity first, then cluster and prioritize

This technique prevents premature convergence on answers and often reveals unexpected angles on familiar problems.

Question Mapping creates visual representations of how questions connect and lead to further inquiries. Starting with a central question, participants graphically branch out with related questions, creating a visual landscape of inquiry that often reveals patterns and gaps.

The Probing Sequence teaches the art of follow-up questions through a simple framework:

- Start with an open question

- Follow with a clarifying question based on the response

- Then ask an implication or meaning question

- Finally, ask a question that challenges an assumption

Example:

- Initial: “How did you approach that project?”

- Clarifying: “What factors most influenced your decision to start with user research?”

- Implication: “How might that initial research phase have shaped the later technical decisions?”

- Assumption-challenging: “What might have happened if you’d integrated developers into the research process?”

Rotating Perspective Questions systematically shift viewpoints to broaden inquiry. When examining any topic, cycle through questions from different perspectives:

- “How would a [different stakeholder] view this situation?”

- “How might this look five years from now?”

- “What would someone who disagrees with us notice that we’re missing?”

- “How would this be approached in a [different industry or cultural context]?”

4. Challenging Yourself: Using Curiosity to Push Boundaries

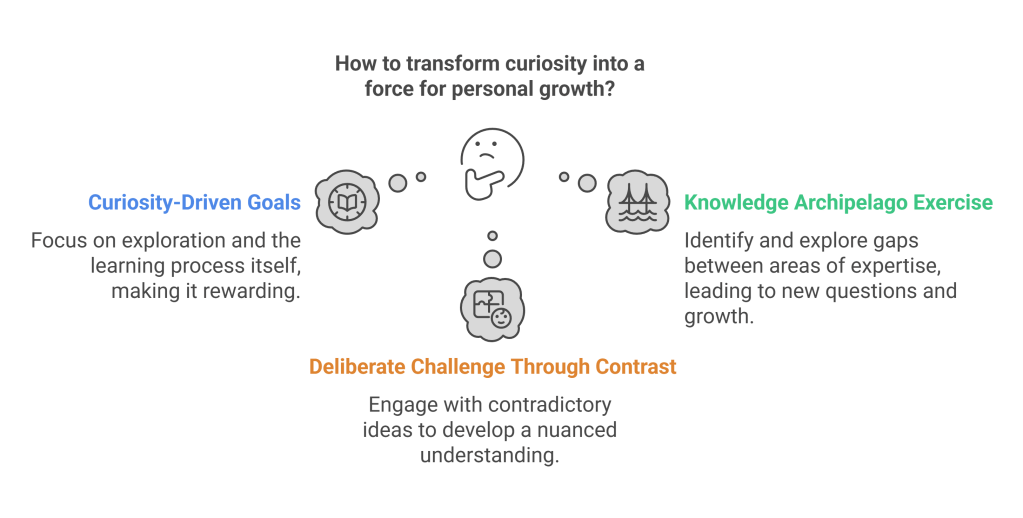

Curiosity naturally leads to challenge when properly channeled. These practices help transform curiosity from mere interest into a force for personal growth:

Curiosity-Driven Goals differ from traditional goals by focusing on exploration rather than specific outcomes. Instead of “Learn Spanish to conversational level,” a curiosity-driven goal might be “Explore how Spanish expresses concepts that don’t translate directly to English.” This approach makes the learning process itself rewarding rather than just the achievement.

The Knowledge Archipelago Exercise helps identify islands of knowledge separated by seas of ignorance. Draw circles representing areas where you have expertise, then deliberately explore the connections and gaps between them. These interdisciplinary spaces often yield the most interesting questions and growth opportunities.

Example: Someone with expertise in both data analysis and customer service might explore the gap between quantitative metrics and qualitative customer experiences, asking how subjective experiences can be meaningfully measured or whether certain aspects of service resist quantification altogether.

Deliberate Challenge Through Contrast involves intentionally engaging with ideas that contradict your existing views or approaches. This isn’t about being argumentative but rather about developing a more nuanced understanding:

- Read the best arguments against positions you hold

- Study methods or frameworks that differ from those you typically use

- Seek out experts who have reached different conclusions from similar starting points

Learning Experiments apply scientific thinking to personal development. Rather than committing to massive changes, design small experiments to test new approaches and ideas:

- Time-bound commitments (e.g., “For two weeks, I’ll start meetings with a different type of question”)

- A/B comparisons (e.g., “I’ll try both visualization and written reflection for processing new information and compare results”)

- Hypothesis testing (e.g., “I believe changing my information consumption patterns will increase creative connections; I’ll test this by…”)

The key is maintaining genuine curiosity about the results rather than seeking to confirm existing beliefs.

5. Curiosity in Different Contexts: Tailored Approaches

While the fundamental nature of curiosity remains constant, how we apply it varies across different domains of life:

Curiosity at Work often requires balancing focused inquiry with practical constraints. Techniques that work particularly well in professional contexts include:

- Pre-mortems that ask “What might cause this project to fail?” before beginning

- Role-rotation days where team members experience different functions

- Designated “exploration time” protected from immediate deliverables

- “How might we…” questions that frame challenges as opportunities for discovery

Curiosity in Relationships deepens connection through genuine interest in others’ inner worlds. Practices include:

- The “Something New” exercise, where partners or friends regularly share something the other doesn’t know about them

- Empathic questioning that focuses on understanding rather than advising or fixing

- “Perspective photo walks” where individuals photograph the same environment but focusing on what catches their individual attention, then discuss the differences

Curiosity in Learning transforms education from knowledge acquisition to genuine inquiry. Approaches include:

- Phenomenon-based learning that starts with observable events and builds toward principles

- Question journals where learners track their evolving questions rather than just their answers

- Hypothesis development before information gathering to make learning more active

- Concept mapping to visualize how ideas connect and where knowledge gaps exist

Curiosity During Crisis helps maintain flexibility and resilience when facing challenges:

- Asking “What opportunities might exist within this challenge?”

- Exploring multiple interpretations of difficult situations

- Questioning limiting assumptions about what’s possible or necessary

- Examining past crises for patterns and insights applicable to current challenges

The Long-Term Practice: Curiosity as a Life Philosophy

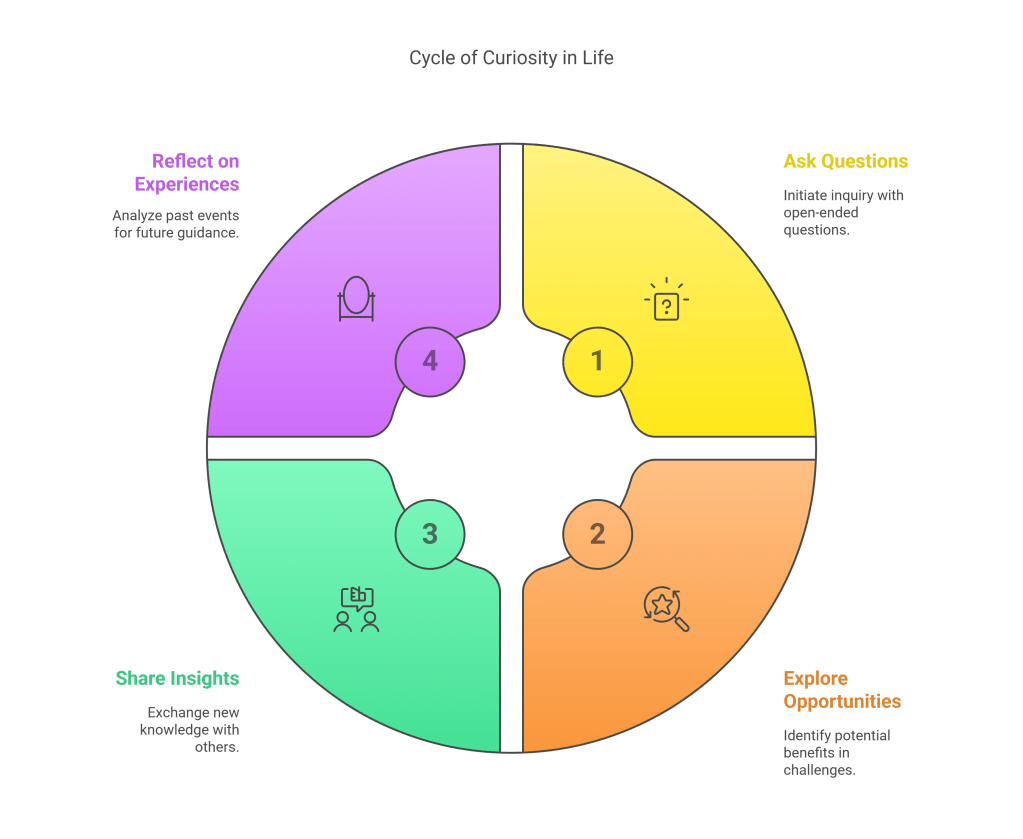

Ultimately, curiosity transcends specific techniques to become a fundamental orientation toward life. Those who sustain curiosity throughout their lives often share certain philosophical perspectives:

Embracing Uncertainty as a space of possibility rather than a problem to be solved. The curious mind is comfortable saying “I don’t know—yet” and views uncertainty as the starting point for discovery rather than a gap to be filled as quickly as possible.

Valuing Process Over Outcomes allows curiosity to flourish even when results are unpredictable. By finding joy in exploration itself, the curious person remains motivated even through setbacks and unexpected turns.

Maintaining Intellectual Humility creates space for new information and perspectives. Recognizing the limitations of our knowledge makes us more receptive to discovery and less likely to dismiss unfamiliar ideas.

Practicing Attentiveness to the present moment enables us to notice details and patterns that might otherwise escape awareness. Curiosity requires this quality of attention—a willingness to look closely and patiently at what’s actually before us rather than rushing to categorize or judge.

Balancing Breadth and Depth of exploration prevents curiosity from becoming either shallow dabbling or narrow specialization. The most vibrant curious minds move between wide-ranging exploration and deep dives into specific areas, allowing each mode to inform the other.

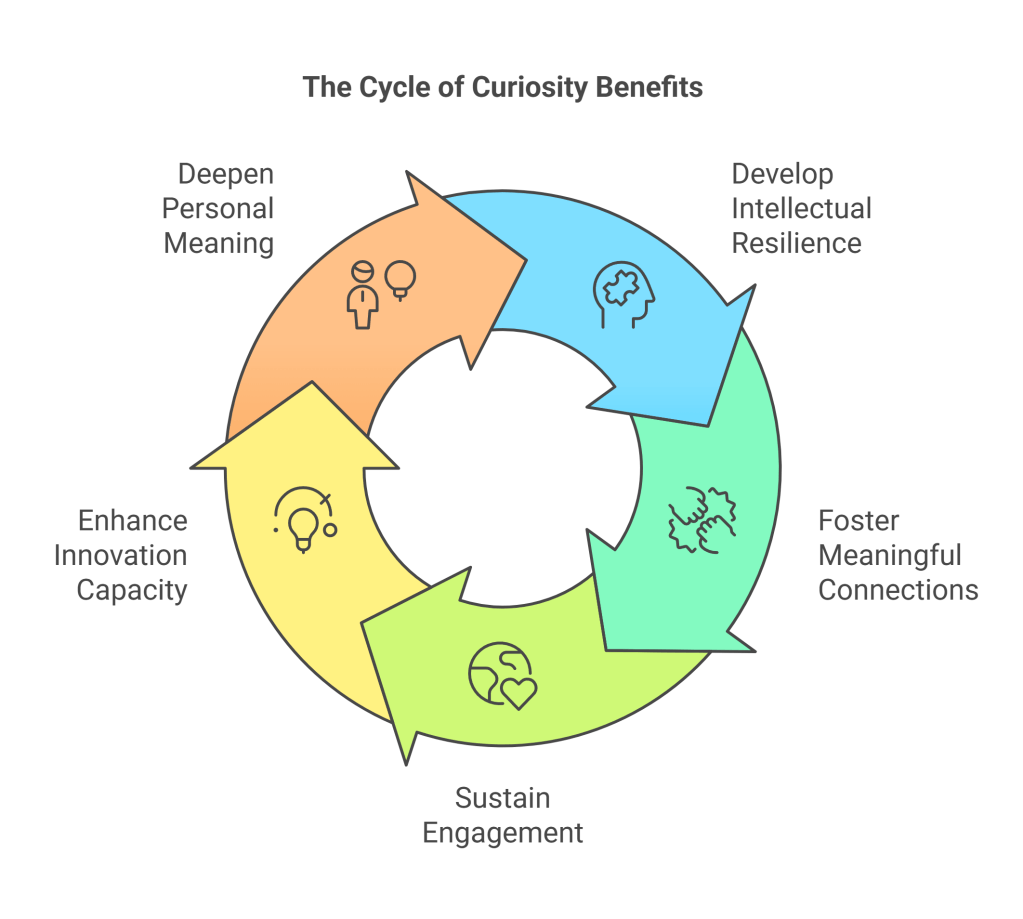

Conclusion: The Compounding Returns of Curiosity

The benefits of cultivating curiosity extend far beyond the immediate pleasure of discovery. Over time, a curious orientation creates compound returns:

Intellectual resilience develops as we become comfortable with uncertainty and complexity. When change inevitably occurs, the curious mind adapts more readily than one invested in maintaining existing knowledge structures.

Meaningful connection grows through genuine interest in others and the world around us. Curiosity naturally counters prejudice and preconception, opening us to authentic engagement with difference.

Sustainable engagement emerges when we’re driven by intrinsic interest rather than external rewards or pressure. While motivation based on achievement or recognition may fluctuate, curiosity provides a more consistent source of energy and direction.

Innovation capacity expands as we build networks of diverse knowledge and perspectives. The most valuable insights often come from unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated ideas—connections that only curiosity can reveal.

Personal meaning deepens as we engage more fully with our experiences. A curious approach transforms even routine activities into opportunities for discovery and growth.

Begin today with one small practice—perhaps a curiosity journal, a different type of question in your next conversation, or fifteen minutes exploring an unfamiliar subject. The journey toward a more curious life doesn’t require dramatic transformation but rather consistent attention to how we engage with ourselves, others, and the world around us.

Remember that curiosity, like any capacity, responds to practice. Each question asked, each assumption examined, each moment of genuine wonder strengthens this essential human quality. In cultivating curiosity, we don’t just gain knowledge—we transform our experience of being alive.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.