In the dynamic world of software development, building applications that are not only functional but also maintainable, scalable, and testable is paramount. As systems grow in complexity, the initial elegance of a codebase can quickly devolve into a tangled mess, often referred to as “spaghetti code.” This is where software design principles become invaluable, acting as guiding stars that illuminate the path towards clean, organized, and resilient architectures. Among the most influential of these principles are SOLID: a mnemonic acronym representing five fundamental design guidelines that, when applied correctly, can transform a fragile application into a robust and adaptable one.

Coined by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), SOLID stands for:

- Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

- Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

These principles are not rigid rules but rather heuristics that encourage us to write code that is easy to understand, modify, and extend without introducing new bugs. They promote loose coupling and high cohesion, two hallmarks of well-designed software. While often discussed in the context of object-oriented programming (OOP), their underlying philosophies are applicable across various paradigms and languages, including Python.

In this extensive article, we will embark on a journey to understand each of the SOLID principles in depth, demonstrating their practical application through a single, continuous, and evolving example: a User Account Management System. We’ll explore common pitfalls by first presenting “bad” code examples, dissecting why they violate a particular principle, and then refactoring them into “correct” solutions that embody SOLID design. By the end, you’ll have a profound understanding of how to leverage SOLID principles to build Python applications that stand the test of time.

The Foundation: Our User Account Management System

Before diving into the principles, let’s establish the core components of our running example. We’ll be focusing on functionalities related to user registration, authentication, and profile management. This system will involve handling user data, hashing passwords, storing information, and potentially sending notifications.

Our journey will begin with a simple, perhaps naive, implementation, and incrementally improve it as we apply each SOLID principle.

1. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) is arguably the simplest to understand but often the hardest to master. It states:

“A class should have only one reason to change.”

In other words, every class, module, or function should have just one responsibility. If a class has more than one reason to change, it means it’s doing too much. This principle aims to create highly cohesive classes that are focused on a single task, leading to a more maintainable and understandable codebase.

The Problem: A Monolithic UserAccount Class

Let’s imagine our initial attempt at building the user account system. A common mistake is to create a single, all-encompassing class that handles various aspects of a user account. Consider the UserAccount class below:

import hashlib

import uuid

import os

import smtplib

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

# --- Bad Example: Violates Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) ---

class UserAccount:

"""

Represents a user account and handles various operations related to it.

This class has too many responsibilities.

"""

def __init__(self, username, password):

self.username = username

self.password_hash = self._hash_password(password)

self.user_id = str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = None # Assuming email might be added later

def _hash_password(self, password):

"""

Hashes the password using SHA256.

This is a security concern and a separate responsibility.

"""

salt = os.urandom(16) # Generate a random salt

hashed_password = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return f"{salt.hex()}:{hashed_password}"

def verify_password(self, password):

"""

Verifies the given password against the stored hash.

Another security-related responsibility.

"""

salt_hex, stored_hash = self.password_hash.split(':')

salt = bytes.fromhex(salt_hex)

input_hash = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return input_hash == stored_hash

def save_to_database(self):

"""

Saves the user account details to a simulated database.

This is a data persistence responsibility.

"""

print(f"Saving user '{self.username}' (ID: {self.user_id}) to database...")

# In a real application, this would interact with a DB like PostgreSQL, MySQL, etc.

# For simplicity, we'll just print.

print(f"User data: Username={self.username}, PasswordHash={self.password_hash}, UserID={self.user_id}")

# Simulate database storage (e.g., a dictionary or list in memory)

# In a real app, this would be a proper ORM or DB client call.

_simulated_db[self.user_id] = {

"username": self.username,

"password_hash": self.password_hash,

"user_id": self.user_id,

"email": self.email

}

print("User saved successfully.")

@classmethod

def load_from_database(cls, user_id):

"""

Loads a user account from the simulated database.

Another data persistence responsibility.

"""

print(f"Loading user with ID '{user_id}' from database...")

user_data = _simulated_db.get(user_id)

if user_data:

print("User loaded successfully.")

# Reconstruct the UserAccount object (simplified for this example)

# In a real scenario, you'd load the hash and username directly.

# This reconstruction is a bit awkward due to the monolithic design.

user = cls(user_data['username'], "dummy_password_for_reconstruction")

user.password_hash = user_data['password_hash']

user.user_id = user_data['user_id']

user.email = user_data['email']

return user

print("User not found.")

return None

def send_welcome_email(self):

"""

Sends a welcome email to the user.

This is a notification responsibility.

"""

if not self.email:

print(f"Error: Cannot send welcome email to {self.username}. Email address not set.")

return

print(f"Attempting to send welcome email to {self.email}...")

try:

# Simulate sending email (requires a local SMTP server or real credentials)

# For demonstration, we'll just print.

sender_email = "noreply@example.com"

receiver_email = self.email

password = "your_email_password" # In real app, use environment variables!

message = MIMEText(f"Welcome, {self.username}! Your account has been created.")

message["Subject"] = "Welcome to Our Service!"

message["From"] = sender_email

message["To"] = receiver_email

# This part is commented out to avoid actual email sending attempts

# with potentially invalid credentials or requiring a local SMTP server.

# with smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.example.com", 465) as smtp:

# smtp.login(sender_email, password)

# smtp.send_message(message)

print(f"Welcome email sent to {self.email} (simulated).")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to send welcome email to {self.email}: {e}")

# Global simulated database (for demonstration purposes only)

_simulated_db = {}

# --- Usage of the bad example ---

print("--- SRP Bad Example ---")

user1 = UserAccount("alice", "secure_password_123")

user1.email = "alice@example.com"

user1.save_to_database()

user2 = UserAccount.load_from_database(user1.user_id)

if user2 and user2.verify_password("secure_password_123"):

print(f"User '{user2.username}' authenticated successfully.")

user2.send_welcome_email()

else:

print("Authentication failed or user not found.")

print("\n--- End SRP Bad Example ---\n")

Why It’s Bad: Violating SRP

The UserAccount class above is a classic example of an SRP violation. It’s a “God object” or a “monolith” that tries to do too much. Let’s break down its numerous responsibilities and why this is problematic:

- User Data Representation: It holds the

username,password_hash,user_id, andemail. This is its primary and legitimate responsibility. - Password Hashing and Verification: The

_hash_passwordandverify_passwordmethods are concerned with cryptographic operations and security. - Data Persistence (Database Interaction):

save_to_databaseandload_from_databaseare responsible for interacting with a storage mechanism (our simulated database). - Notification (Email Sending):

send_welcome_emailis responsible for sending emails.

Reasons why this design is problematic:

- Multiple Reasons to Change:

- If the password hashing algorithm needs to change (e.g., from SHA256 to Argon2), the

UserAccountclass must be modified. - If the database technology changes (e.g., from a relational database to a NoSQL database), the

UserAccountclass must be modified. - If the email sending service changes (e.g., from SMTP to a third-party API like SendGrid), the

UserAccountclass must be modified. - If the core user data structure changes, the UserAccount class must be modified.Each of these changes is a “reason to change” for the UserAccount class, directly violating SRP.

- If the password hashing algorithm needs to change (e.g., from SHA256 to Argon2), the

- Tight Coupling: The

UserAccountclass is tightly coupled to specific implementations of hashing, database interaction, and email sending. This makes it difficult to swap out components or test them independently. - Difficulty in Testing: How would you test the

UserAccountclass? You’d need to mock the database, potentially a live SMTP server, and ensure hashing works correctly. This makes unit testing cumbersome and fragile. A single test failure could be due to any of these unrelated responsibilities. - Reduced Readability and Understandability: A class with many responsibilities is harder to read and understand. Its methods are scattered across different concerns, making it difficult to grasp its core purpose at a glance.

- Lower Reusability: Can you reuse the password hashing logic without the database interaction? No, because it’s bundled together. This reduces the modularity and reusability of components.

The Solution: Segregating Responsibilities

To adhere to SRP, we need to break down the monolithic UserAccount class into smaller, more focused classes, each with a single, well-defined responsibility.

import hashlib

import uuid

import os

import smtplib

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod # For defining abstract base classes/interfaces

# --- Correct Example: Adheres to Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) ---

# 1. User Data Representation (Core User Entity)

class User:

"""

Represents the core user entity with its data.

Responsibility: Hold user data.

"""

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None # This will be set by a PasswordHasher

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

# 2. Password Hashing and Verification

class PasswordHasher:

"""

Handles password hashing and verification.

Responsibility: Secure password operations.

"""

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

"""Hashes a plain-text password."""

salt = os.urandom(16) # Generate a random salt

hashed_password = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return f"{salt.hex()}:{hashed_password}"

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

"""Verifies a plain-text password against a stored hash."""

try:

salt_hex, stored_hash_value = stored_hash.split(':')

salt = bytes.fromhex(salt_hex)

input_hash = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return input_hash == stored_hash_value

except ValueError:

# Handle cases where the stored_hash format is incorrect

return False

# 3. Data Persistence (User Repository)

# We'll use an abstract base class for the repository to prepare for OCP and DIP.

class IUserRepository(ABC):

"""

Abstract Base Class for user data persistence.

Defines the contract for saving and loading users.

Responsibility: Define user persistence operations.

"""

@abstractmethod

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

"""Saves a user and their password hash."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user by username."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user by ID."""

pass

# Concrete implementation of the user repository (simulated in-memory)

class InMemoryUserRepository(IUserRepository):

"""

Simulated in-memory user repository.

Responsibility: Store and retrieve user data in memory.

"""

_simulated_db = {} # Class-level dictionary to simulate storage

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

"""Saves a user and their password hash to memory."""

print(f"Saving user '{user.username}' (ID: {user.user_id}) to in-memory DB...")

self._simulated_db[user.user_id] = {

"username": user.username,

"password_hash": password_hash,

"user_id": user.user_id,

"email": user.email

}

print("User saved successfully to in-memory DB.")

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user by username from memory."""

print(f"Loading user by username '{username}' from in-memory DB...")

for user_data in self._simulated_db.values():

if user_data["username"] == username:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

print(f"User '{username}' found in in-memory DB.")

return user

print(f"User '{username}' not found in in-memory DB.")

return None

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user by ID from memory."""

print(f"Loading user by ID '{user_id}' from in-memory DB...")

user_data = self._simulated_db.get(user_id)

if user_data:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

print(f"User with ID '{user_id}' found in in-memory DB.")

return user

print(f"User with ID '{user_id}' not found in in-memory DB.")

return None

# 4. Notification Service (Email Sender)

class EmailNotifier:

"""

Handles sending email notifications.

Responsibility: Send emails.

"""

def send_welcome_email(self, user: User):

"""Sends a welcome email to the specified user."""

if not user.email:

print(f"Error: Cannot send welcome email to {user.username}. Email address not set.")

return

print(f"Attempting to send welcome email to {user.email} (simulated)...")

try:

sender_email = "noreply@example.com"

receiver_email = user.email

message = MIMEText(f"Welcome, {user.username}! Your account has been created.")

message["Subject"] = "Welcome to Our Service!"

message["From"] = sender_email

message["To"] = receiver_email

# This part is commented out to avoid actual email sending attempts

# with potentially invalid credentials or requiring a local SMTP server.

# with smtplib.SMTP_SSL("smtp.example.com", 465) as smtp:

# smtp.login(sender_email, "your_email_password") # Use environment variables!

# smtp.send_message(message)

print(f"Welcome email sent to {user.email} (simulated).")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to send welcome email to {user.email}: {e}")

# 5. High-level User Account Service (Orchestrator)

# This class will coordinate the responsibilities of the other classes.

# Its responsibility is to manage the user account creation and authentication flow.

class UserAccountService:

"""

Manages user account creation and authentication.

Orchestrates interactions between User, PasswordHasher, UserRepository, and EmailNotifier.

Responsibility: Orchestrate user account business logic.

"""

def __init__(self, user_repository: IUserRepository, password_hasher: PasswordHasher, email_notifier: EmailNotifier):

self.user_repository = user_repository

self.password_hasher = password_hasher

self.email_notifier = email_notifier

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None) -> User:

"""Registers a new user."""

if self.user_repository.get_by_username(username):

print(f"Error: User with username '{username}' already exists.")

return None

user = User(username, email=email)

hashed_password = self.password_hasher.hash_password(password)

self.user_repository.save(user, hashed_password)

print(f"User '{username}' registered successfully.")

if email:

self.email_notifier.send_welcome_email(user)

return user

def authenticate_user(self, username: str, password: str) -> User:

"""Authenticates an existing user."""

user = self.user_repository.get_by_username(username)

if user and user.password_hash:

if self.password_hasher.verify_password(password, user.password_hash):

print(f"User '{username}' authenticated successfully.")

return user

print(f"Authentication failed for user '{username}'.")

return None

def get_user_profile(self, user_id: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user's profile by ID."""

return self.user_repository.get_by_id(user_id)

# --- Usage of the good example ---

print("\n--- SRP Good Example ---")

# Instantiate the concrete implementations

password_hasher = PasswordHasher()

user_repo = InMemoryUserRepository()

email_notifier = EmailNotifier()

# Inject dependencies into the UserAccountService

user_service = UserAccountService(user_repo, password_hasher, email_notifier)

# Register a user

new_user = user_service.register_user("bob_srp", "srp_secure_pass", "bob.srp@example.com")

if new_user:

# Authenticate the user

authenticated_user = user_service.authenticate_user("bob_srp", "srp_secure_pass")

if authenticated_user:

print(f"Authenticated user: {authenticated_user}")

# Try to register the same user again

user_service.register_user("bob_srp", "another_pass", "bob.srp@example.com")

# Get user profile

retrieved_user = user_service.get_user_profile(new_user.user_id)

if retrieved_user:

print(f"Retrieved user profile: {retrieved_user}")

print("\n--- End SRP Good Example ---\n")

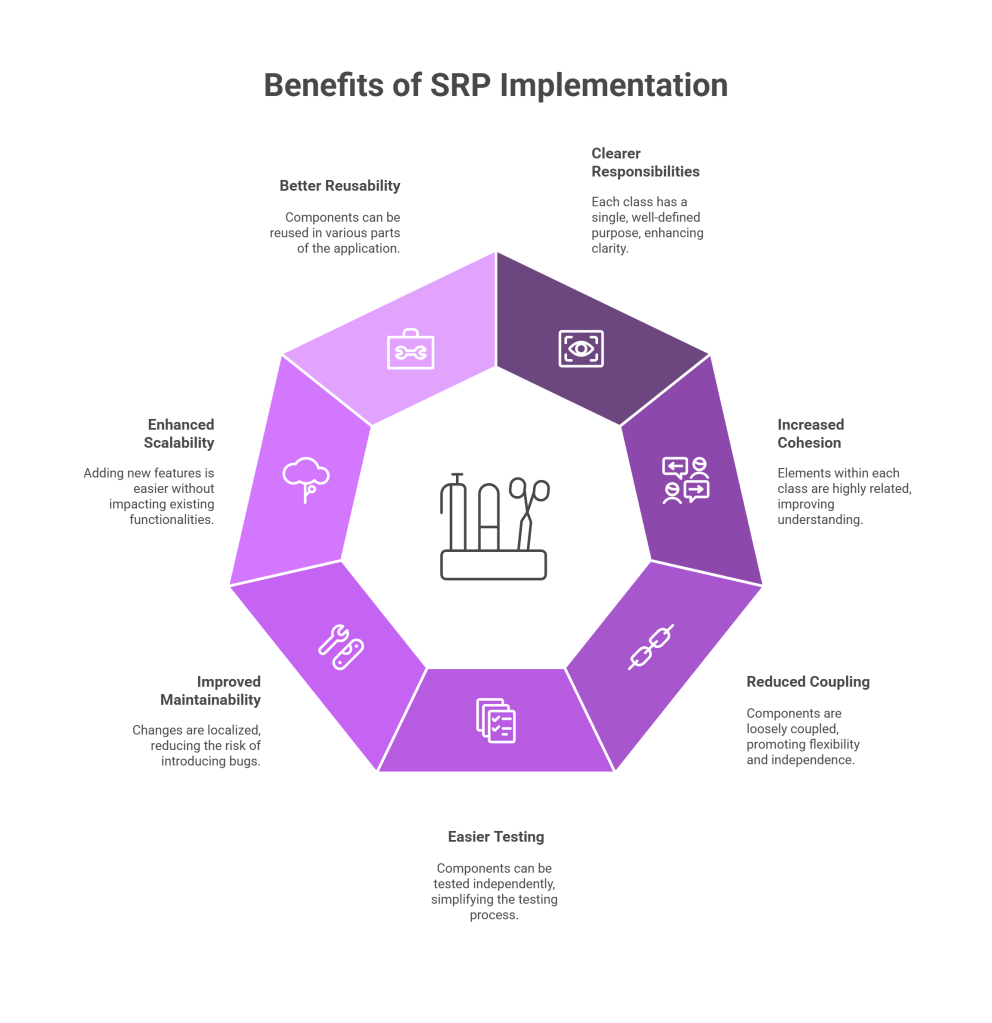

Benefits of Adhering to SRP

By refactoring our UserAccount class into User, PasswordHasher, IUserRepository (and InMemoryUserRepository), EmailNotifier, and UserAccountService, we achieve significant benefits:

- Clearer Responsibilities: Each class now has a single, well-defined purpose.

User: Only holds user data.PasswordHasher: Only handles password hashing and verification.IUserRepository/InMemoryUserRepository: Only handles user data persistence.EmailNotifier: Only handles sending emails.UserAccountService: Only orchestrates the business logic for user accounts.

- Increased Cohesion: The elements within each class are highly related to its single responsibility. This makes the code easier to understand and reason about.

- Reduced Coupling: Components are now loosely coupled. The

UserAccountServicedoesn’t care how passwords are hashed or where users are stored; it just knows it needs aPasswordHasherand anIUserRepository. This is a crucial step towards the Dependency Inversion Principle. - Easier Testing: Each component can be tested independently.

- You can test

PasswordHasherin isolation without needing a database or email server. - You can test

InMemoryUserRepositorywithout complex setups. - You can test

UserAccountServiceby mocking its dependencies (e.g., providing a mockIUserRepositoryfor tests), making unit tests faster and more reliable.

- You can test

- Improved Maintainability: Changes to one responsibility (e.g., changing the hashing algorithm) are localized to one class (

PasswordHasher), reducing the risk of introducing bugs in unrelated parts of the system. - Enhanced Scalability: As the system grows, it’s easier to add new features or modify existing ones without impacting unrelated functionalities. For instance, adding SMS notifications would involve creating a new

SMSNotifierclass, not modifyingUserAccountServiceorUser. - Better Reusability: The

PasswordHashercan now be reused in any part of the application that needs password hashing, not just for user accounts. TheEmailNotifiercan be used for any email sending needs.

The SRP is the cornerstone of good object-oriented design. By ensuring each class does one thing and does it well, we lay a solid foundation for building extensible and maintainable software.

2. Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

The Open/Closed Principle (OCP) is one of the most powerful and often misunderstood SOLID principles. It states:

“Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.”

This means that you should be able to add new functionality to a system without altering existing, working code. When you modify existing code, you risk introducing new bugs into previously tested and stable parts of the system. Instead, OCP encourages you to extend functionality by adding new code, typically through inheritance or composition, and relying on abstractions.

The Problem: Modifying for New Functionality

Let’s revisit our PasswordHasher from the SRP example. While we successfully extracted it into its own class, what if we initially implemented it with a specific hashing algorithm (like SHA256) and later decided to switch to a more robust, industry-standard algorithm like bcrypt?

import hashlib

import os

# --- Bad Example: Violates Open/Closed Principle (OCP) ---

class PasswordHasherV1:

"""

Initial password hasher implementation using SHA256.

This class is not open for extension without modification for new algorithms.

"""

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

"""Hashes a plain-text password using SHA256."""

salt = os.urandom(16)

hashed_password = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return f"{salt.hex()}:{hashed_password}"

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

"""Verifies a plain-text password against a stored SHA256 hash."""

try:

salt_hex, stored_hash_value = stored_hash.split(':')

salt = bytes.fromhex(salt_hex)

input_hash = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return input_hash == stored_hash_value

except ValueError:

return False

# Imagine our UserAccountService directly uses this concrete implementation

# (This is a simplified snippet to show the OCP violation context)

class UserAccountServiceV1:

def __init__(self):

self.password_hasher = PasswordHasherV1() # Direct dependency on concrete class

# ... other dependencies

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None):

hashed_password = self.password_hasher.hash_password(password)

# ... save user ...

print(f"User '{username}' registered with SHA256 hash.")

return hashed_password # Return hash for demonstration

def authenticate_user(self, username: str, password: str):

# ... load user ...

stored_hash = "some_hash_from_db" # Placeholder

if self.password_hasher.verify_password(password, stored_hash):

print(f"User '{username}' authenticated using SHA256.")

return True

return False

print("--- OCP Bad Example ---")

service_v1 = UserAccountServiceV1()

# Simulate usage

hashed_pass_v1 = service_v1.register_user("charlie_ocp", "ocp_pass_123")

print(f"Hashed password (SHA256): {hashed_pass_v1}")

service_v1.authenticate_user("charlie_ocp", hashed_pass_v1) # This authentication would fail without proper user loading

print("\n--- End OCP Bad Example ---\n")

Why It’s Bad: Violating OCP

The PasswordHasherV1 class, and its direct usage by UserAccountServiceV1, violates the Open/Closed Principle for the following reasons:

- Modification for Extension: If we decide to switch from SHA256 to bcrypt, we would have to modify the

PasswordHasherV1class itself. We’d either:- Change the internal implementation of

hash_passwordandverify_passwordto use bcrypt. This directly modifies existing code. - Add conditional logic within

PasswordHasherV1to choose between SHA256 and bcrypt based on some configuration. This still modifies the class and makes it more complex.

- Change the internal implementation of

- Impact on Dependent Code: Any code that directly uses

PasswordHasherV1(likeUserAccountServiceV1in our snippet) would implicitly be affected by this change. Even if the method signatures remain the same, the underlying behavior changes, potentially requiring re-testing of all dependent modules. - Risk of Regression: Every time you modify existing, tested code, there’s a risk of introducing new bugs (regressions). OCP aims to minimize this risk by encouraging additions rather than alterations.

- Lack of Flexibility: The system is rigid. It’s hard to introduce new hashing algorithms or switch between them without touching the core

PasswordHasherlogic.

The Solution: Abstraction and Polymorphism

To adhere to OCP, we need to introduce an abstraction (an interface or abstract base class) for password hashing. Our UserAccountService will then depend on this abstraction, not on a concrete implementation. New hashing algorithms can be added by creating new concrete classes that implement the abstraction, without modifying existing code.

import hashlib

import os

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from passlib.hash import bcrypt # Requires 'pip install passlib'

# --- Correct Example: Adheres to Open/Closed Principle (OCP) ---

# 1. Abstraction for Password Hashing (Open for Extension)

class IPasswordHasher(ABC):

"""

Abstract Base Class (interface) for password hashing.

Defines the contract for any password hasher.

"""

@abstractmethod

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

"""Hashes a plain-text password."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

"""Verifies a plain-text password against a stored hash."""

pass

# 2. Concrete Implementation: SHA256 Hasher (Existing, Closed for Modification)

class SHA256Hasher(IPasswordHasher):

"""

Concrete implementation of IPasswordHasher using SHA256.

This class is now closed for modification (unless SHA256 algorithm itself changes,

which is unlikely and would warrant a new hasher anyway).

"""

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

salt = os.urandom(16)

hashed_password = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return f"sha256:{salt.hex()}:{hashed_password}" # Prefix to identify algorithm

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

try:

prefix, salt_hex, stored_hash_value = stored_hash.split(':')

if prefix != "sha256": # Ensure we are verifying the correct hash type

return False

salt = bytes.fromhex(salt_hex)

input_hash = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return input_hash == stored_hash_value

except ValueError:

return False

# 3. Concrete Implementation: BCrypt Hasher (New, Extension)

class BCryptHasher(IPasswordHasher):

"""

Concrete implementation of IPasswordHasher using BCrypt.

This is a new extension, added without modifying existing code.

"""

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

# bcrypt.hash() automatically handles salting

return f"bcrypt:{bcrypt.hash(password)}" # Prefix to identify algorithm

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

try:

prefix, bcrypt_hash = stored_hash.split(':', 1) # Split only on first colon

if prefix != "bcrypt":

return False

return bcrypt.verify(password, bcrypt_hash)

except ValueError:

return False

except Exception as e: # Catch passlib specific errors

print(f"BCrypt verification error: {e}")

return False

# 4. User Account Service (Depends on Abstraction)

# Reusing the User, IUserRepository, EmailNotifier from SRP example

# (Full code for these classes not repeated here for brevity, assume they are available)

# User, IUserRepository, InMemoryUserRepository, EmailNotifier are from SRP example.

# This is our UserAccountService from the SRP example, now explicitly depending on IPasswordHasher

class UserAccountServiceOCP:

"""

Manages user account creation and authentication.

Depends on the IPasswordHasher abstraction.

"""

def __init__(self, user_repository: IUserRepository, password_hasher: IPasswordHasher, email_notifier: EmailNotifier):

self.user_repository = user_repository

self.password_hasher = password_hasher # Dependency on abstraction!

self.email_notifier = email_notifier

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None) -> User:

if self.user_repository.get_by_username(username):

print(f"Error: User with username '{username}' already exists.")

return None

user = User(username, email=email)

hashed_password = self.password_hasher.hash_password(password)

self.user_repository.save(user, hashed_password) # Save user and their specific hash

user.password_hash = hashed_password # Update user object with hash for consistency

print(f"User '{username}' registered successfully using {self.password_hasher.__class__.__name__}.")

if email:

self.email_notifier.send_welcome_email(user)

return user

def authenticate_user(self, username: str, password: str) -> User:

user = self.user_repository.get_by_username(username)

if user and user.password_hash:

# The service doesn't need to know *which* hasher was used to store it,

# as long as the hasher passed to it can verify the stored format.

# For a real system, you might need a "PasswordVerifier" that can

# determine the hash type from the stored hash and use the correct

# hasher, or store the hasher type alongside the hash.

# For simplicity here, we assume the current hasher can verify it.

# A more robust solution might involve a "PasswordHashResolver" that

# iterates through known hashers based on the hash prefix.

if self.password_hasher.verify_password(password, user.password_hash):

print(f"User '{username}' authenticated successfully using {self.password_hasher.__class__.__name__}.")

return user

print(f"Authentication failed for user '{username}'.")

return None

# --- Usage of the good example ---

print("\n--- OCP Good Example ---")

# Instantiate dependencies

user_repo_ocp = InMemoryUserRepository()

email_notifier_ocp = EmailNotifier()

# Scenario 1: Using SHA256 Hasher

print("\n--- Using SHA256 Hasher ---")

sha256_hasher = SHA256Hasher()

user_service_sha256 = UserAccountServiceOCP(user_repo_ocp, sha256_hasher, email_notifier_ocp)

user_sha = user_service_sha256.register_user("david_ocp_sha", "ocp_pass_sha", "david.sha@example.com")

if user_sha:

user_service_sha256.authenticate_user("david_ocp_sha", "ocp_pass_sha")

user_service_sha256.authenticate_user("david_ocp_sha", "wrong_pass")

# Scenario 2: Using BCrypt Hasher (new functionality, no modification to UserAccountServiceOCP)

print("\n--- Using BCrypt Hasher ---")

bcrypt_hasher = BCryptHasher()

user_service_bcrypt = UserAccountServiceOCP(user_repo_ocp, bcrypt_hasher, email_notifier_ocp)

user_bcrypt = user_service_bcrypt.register_user("eve_ocp_bcrypt", "ocp_pass_bcrypt", "eve.bcrypt@example.com")

if user_bcrypt:

user_service_bcrypt.authenticate_user("eve_ocp_bcrypt", "ocp_pass_bcrypt")

user_service_bcrypt.authenticate_user("eve_ocp_bcrypt", "wrong_pass")

# A more advanced scenario for authentication:

# If you store different hash types in the DB, your authentication

# mechanism needs to be smart enough to pick the right verifier.

# This often involves storing a hash "type" or "prefix" with the hash itself.

# Let's simulate that:

print("\n--- Authenticating mixed hash types (advanced OCP/DIP) ---")

class PasswordVerifierService:

def __init__(self, hashers: list[IPasswordHasher]):

self.hashers = {hasher.__class__.__name__.lower().replace('hasher', ''): hasher for hasher in hashers}

def verify(self, password: str, stored_hash_with_prefix: str) -> bool:

try:

prefix = stored_hash_with_prefix.split(':', 1)[0]

# Map prefix to hasher type (e.g., "sha256" -> "sha256hasher", "bcrypt" -> "bcrypthasher")

hasher_key = prefix.lower()

if hasher_key in self.hashers:

return self.hashers[hasher_key].verify_password(password, stored_hash_with_prefix)

print(f"Unknown hash prefix: {prefix}")

return False

except IndexError:

print("Invalid hash format.")

return False

# Register a user with SHA256

user_sha_2 = user_service_sha256.register_user("frank_ocp_sha", "ocp_pass_sha_2", "frank.sha@example.com")

# Register a user with BCrypt

user_bcrypt_2 = user_service_bcrypt.register_user("grace_ocp_bcrypt", "ocp_pass_bcrypt_2", "grace.bcrypt@example.com")

# Simulate retrieving stored hashes (from our InMemoryUserRepository)

# In a real app, these would come from the DB.

frank_user_data = user_repo_ocp.get_by_username("frank_ocp_sha")

grace_user_data = user_repo_ocp.get_by_username("grace_ocp_bcrypt")

if frank_user_data and grace_user_data:

# Create a verifier service with all available hashers

verifier_service = PasswordVerifierService([SHA256Hasher(), BCryptHasher()])

print(f"\nVerifying Frank (SHA256):")

verifier_service.verify("ocp_pass_sha_2", frank_user_data.password_hash)

verifier_service.verify("wrong_pass", frank_user_data.password_hash)

print(f"\nVerifying Grace (BCrypt):")

verifier_service.verify("ocp_pass_bcrypt_2", grace_user_data.password_hash)

verifier_service.verify("wrong_pass", grace_user_data.password_hash)

print("\n--- End OCP Good Example ---\n")

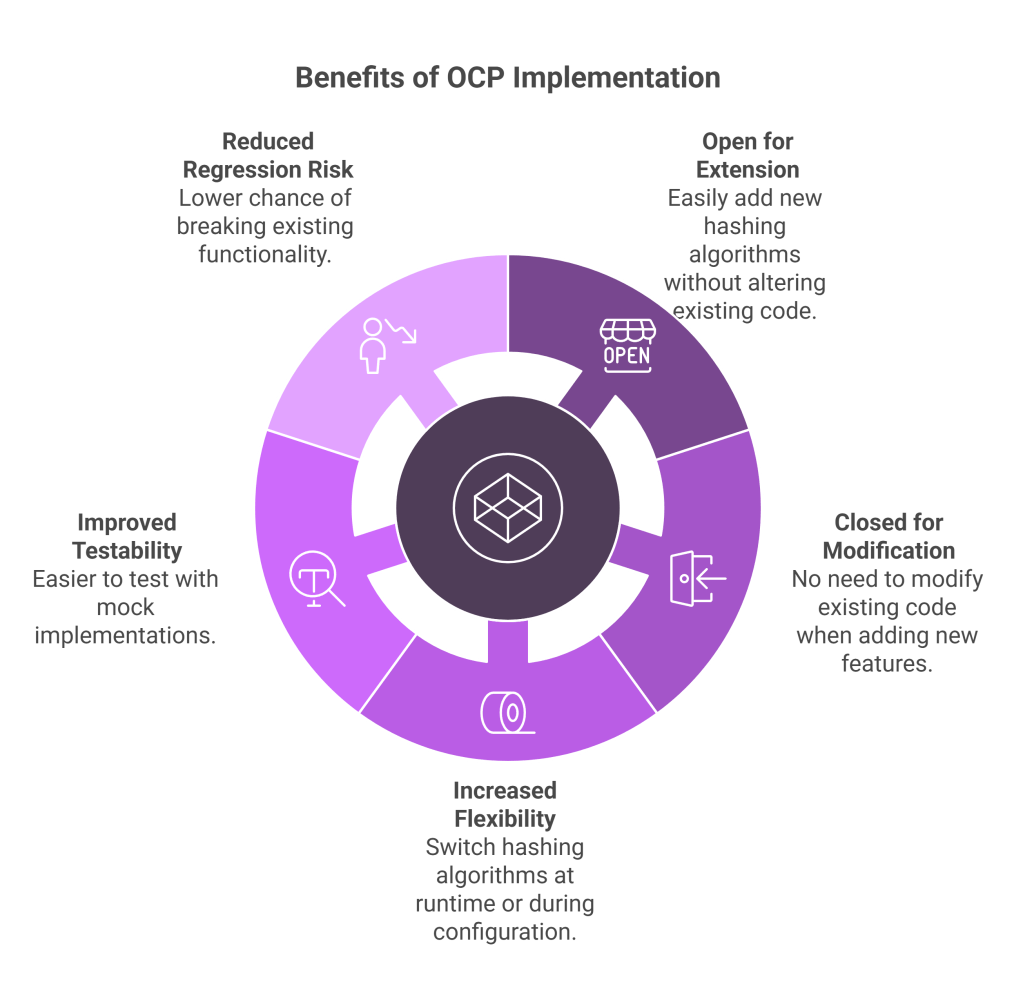

Benefits of Adhering to OCP

By introducing the IPasswordHasher abstraction and concrete implementations like SHA256Hasher and BCryptHasher, we achieve the following benefits:

- Open for Extension: We can easily add new hashing algorithms (e.g., Argon2, Scrypt) by simply creating a new class that implements

IPasswordHasher. This new class extends the system’s capabilities. - Closed for Modification: The

UserAccountServiceOCP(and any other client code that depends onIPasswordHasher) does not need to be modified when a new hashing algorithm is introduced. It continues to work with theIPasswordHasherabstraction, relying on polymorphism to handle the specific implementation. This significantly reduces the risk of introducing bugs into stable code. - Increased Flexibility: The system becomes much more adaptable. We can switch the hashing algorithm used by the

UserAccountServiceOCPat runtime or during configuration, simply by injecting a differentIPasswordHasherimplementation. - Improved Testability: It’s easier to test the

UserAccountServiceOCPbecause we can inject mockIPasswordHasherimplementations that simulate hashing behavior without performing actual cryptographic operations. This speeds up tests and makes them more reliable. - Reduced Regression Risk: Since existing code remains untouched when new features are added, the likelihood of breaking existing functionality is drastically reduced.

OCP is a cornerstone for building truly extensible and maintainable systems. It encourages designing with future changes in mind, making your codebase resilient to evolving requirements.

3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) is perhaps the most subtle of the SOLID principles, yet it’s crucial for ensuring the correctness and robustness of polymorphic systems. It states:

“Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types without altering the correctness of the program.”

In simpler terms, if you have a base class (or interface) and a subclass (or implementation), you should be able to use an object of the subclass wherever an object of the base class is expected, and the program should still behave correctly without unexpected errors or changes in behavior. This means that subclasses should extend the functionality of the base class without violating its established contract (e.g., method signatures, pre-conditions, post-conditions, invariants).

The Problem: Breaking the Contract

Let’s consider our IUserRepository abstraction from the SRP example. We have InMemoryUserRepository. What if we introduce another type of repository that doesn’t fully adhere to the expected behavior, or introduces unexpected side effects?

Imagine we want to add a GuestUserRepository for anonymous users who can only view public profiles, but not create or manage their own accounts.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

# Re-using User class definition from SRP example

class User:

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

# Re-using IUserRepository definition from SRP example

class IUserRepository(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

pass

# Re-using InMemoryUserRepository from SRP example

class InMemoryUserRepository(IUserRepository):

_simulated_db = {}

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

print(f"Saving user '{user.username}' (ID: {user.user_id}) to in-memory DB.")

self._simulated_db[user.user_id] = {

"username": user.username,

"password_hash": password_hash,

"user_id": user.user_id,

"email": user.email

}

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

for user_data in self._simulated_db.values():

if user_data["username"] == username:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

user_data = self._simulated_db.get(user_id)

if user_data:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

# --- Bad Example: Violates Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) ---

class GuestUserRepository(IUserRepository):

"""

A repository for guest users. This implementation violates LSP

because it breaks the contract of IUserRepository for 'save'.

"""

_guest_users = {

"guest1": User("guest1", user_id="guest_id_1", email="guest1@example.com"),

"guest2": User("guest2", user_id="guest_id_2", email="guest2@example.com")

}

# For simplicity, guest users don't have passwords in this specific example.

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

"""

Violates LSP: This method does nothing or raises an error,

breaking the expectation that a user can be saved.

"""

print(f"LSP Violation: Cannot save user '{user.username}' in GuestUserRepository. This repository is read-only for guests.")

# Option 1: Do nothing (silent failure, breaks post-condition)

# Option 2: Raise NotImplementedError (breaks expected behavior)

# raise NotImplementedError("GuestUserRepository does not support saving users.")

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a guest user by username."""

print(f"Loading guest user '{username}' from GuestUserRepository.")

return self._guest_users.get(username)

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a guest user by ID."""

print(f"Loading guest user by ID '{user_id}' from GuestUserRepository.")

for user in self._guest_users.values():

if user.user_id == user_id:

return user

return None

# Client code that expects any IUserRepository

class UserRegistrationServiceLSP:

def __init__(self, user_repository: IUserRepository):

self.user_repository = user_repository

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None) -> User:

print(f"Attempting to register user '{username}'...")

# This client code expects user_repository.save to actually save the user.

new_user = User(username, email=email)

# Dummy password hash for demonstration

dummy_hash = "dummy_hash_for_guest"

self.user_repository.save(new_user, dummy_hash)

# If save does nothing, the rest of the logic might fail or be incorrect.

print(f"Registration attempt for '{username}' completed.")

return new_user # This user object might not be persisted!

print("--- LSP Bad Example ---")

# Using the InMemoryUserRepository (behaves as expected)

print("\n--- Using InMemoryUserRepository ---")

in_memory_repo_lsp = InMemoryUserRepository()

reg_service_in_memory = UserRegistrationServiceLSP(in_memory_repo_lsp)

in_memory_user = reg_service_in_memory.register_user("fred_lsp", "lsp_pass", "fred@example.com")

if in_memory_repo_lsp.get_by_username("fred_lsp"):

print("Fred was successfully registered (as expected).")

else:

print("Fred was NOT registered (unexpected).")

# Using the GuestUserRepository (violates LSP)

print("\n--- Using GuestUserRepository (LSP Violation) ---")

guest_repo_lsp = GuestUserRepository()

reg_service_guest = UserRegistrationServiceLSP(guest_repo_lsp)

guest_user_attempt = reg_service_guest.register_user("new_guest", "guest_pass", "new_guest@example.com")

# The client code (UserRegistrationServiceLSP) expects 'save' to persist the user.

# But GuestUserRepository's save method does nothing.

if guest_repo_lsp.get_by_username("new_guest"):

print("New guest was successfully registered (unexpected behavior).")

else:

print("New guest was NOT registered (expected behavior, but LSP violation).") # This will be printed

print("\n--- End LSP Bad Example ---\n")

Why It’s Bad: Violating LSP

The GuestUserRepository violates LSP in a subtle but critical way:

- Breaking the Contract of

save: TheIUserRepositoryinterface implies thatsavewill persist a user.InMemoryUserRepositoryfulfills this contract. However,GuestUserRepository‘ssavemethod explicitly does not save the user; it either does nothing (silent failure) or raises anNotImplementedError. - Unexpected Behavior for Client Code: The

UserRegistrationServiceLSPis designed to work with anyIUserRepository. It callssaveassuming the user will be persisted. WhenGuestUserRepositoryis substituted, this assumption is broken. Theregister_usermethod completes without an error, but the user is never actually saved, leading to incorrect program state or silent data loss. - Violating Pre/Post Conditions: If the

savemethod’s contract includes a post-condition like “the user will be retrievable after this method completes,” thenGuestUserRepositoryfails this post-condition. - Fragile Client Code: Client code that uses

IUserRepositorybecomes fragile because it has to anticipate and handle the specific non-standard behavior ofGuestUserRepository. This often leads toif type(repo) is GuestUserRepository:checks, which is an anti-pattern that defeats the purpose of polymorphism.

LSP is about behavioral subtyping. A subclass should not just have the same method signatures; it should also behave in a way that is consistent with the expectations set by its base type.

The Solution: Adhering to the Contract or Segregating Interfaces

To adhere to LSP, we have two primary approaches, depending on the exact requirement:

- Ensure Strict Adherence: If

GuestUserRepositorymust be a type ofIUserRepository, then itssavemethod must fulfill the contract, perhaps by saving to a temporary guest session or a specific guest-only storage. If it genuinely cannot save, then it likely shouldn’t be a subtype ofIUserRepository. - Segregate Interfaces (ISP): If some repositories support saving and others don’t, it might be a sign that

IUserRepositoryis too broad and should be split into smaller, more specific interfaces (e.g.,IUserReadableRepositoryandIUserWritableRepository). This is where LSP often leads into ISP.

For this example, let’s assume GuestUserRepository truly cannot save, and therefore, it should not implement the save method if it’s part of a IUserRepository that mandates saving. The correct LSP approach is to either make GuestUserRepository not implement IUserRepository at all, or to refine IUserRepository using ISP.

Let’s demonstrate the ISP solution, as it’s a common way to resolve LSP violations where a subtype genuinely cannot fulfill all base type operations. We’ll introduce IUserReadableRepository and IUserWritableRepository.

import uuid

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

# Re-using User class definition from SRP example

class User:

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

# --- Correct Example: Adheres to Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) via ISP ---

# 1. Segregated Interfaces (Adhering to ISP, which helps LSP)

class IUserReadableRepository(ABC):

"""Interface for repositories that can read users."""

@abstractmethod

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

pass

class IUserWritableRepository(ABC):

"""Interface for repositories that can write/save users."""

@abstractmethod

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

pass

# 2. Concrete Implementation: InMemoryUserRepository (Implements both)

class InMemoryUserRepository(IUserReadableRepository, IUserWritableRepository):

_simulated_db = {}

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

print(f"Saving user '{user.username}' (ID: {user.user_id}) to in-memory DB.")

self._simulated_db[user.user_id] = {

"username": user.username,

"password_hash": password_hash,

"user_id": user.user_id,

"email": user.email

}

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

for user_data in self._simulated_db.values():

if user_data["username"] == username:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

user_data = self._simulated_db.get(user_id)

if user_data:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

# 3. Concrete Implementation: GuestUserRepository (Implements only readable interface)

class GuestUserRepository(IUserReadableRepository):

"""

A repository for guest users, now correctly implementing only the readable interface.

This adheres to LSP because it doesn't pretend to support 'save'.

"""

_guest_users = {

"guest1": User("guest1", user_id="guest_id_1", email="guest1@example.com"),

"guest2": User("guest2", user_id="guest_id_2", email="guest2@example.com")

}

# No 'save' method here, as it's not part of IUserReadableRepository.

# This ensures that clients expecting writable functionality cannot use this class.

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

print(f"Loading guest user '{username}' from GuestUserRepository.")

return self._guest_users.get(username)

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

print(f"Loading guest user by ID '{user_id}' from GuestUserRepository.")

for user in self._guest_users.values():

if user.user_id == user_id:

return user

return None

# 4. Client code now depends on the appropriate interface

class UserRegistrationServiceLSPCorrect:

def __init__(self, user_writable_repository: IUserWritableRepository):

# This service specifically needs a repository that can write.

self.user_repository = user_writable_repository

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None) -> User:

print(f"Attempting to register user '{username}'...")

new_user = User(username, email=email)

dummy_hash = "dummy_hash_for_reg" # In real app, use a real hasher

self.user_repository.save(new_user, dummy_hash)

print(f"Registration attempt for '{username}' completed. User should be persisted.")

return new_user

class UserProfileViewerLSPCorrect:

def __init__(self, user_readable_repository: IUserReadableRepository):

# This service only needs a repository that can read.

self.user_repository = user_readable_repository

def view_user_profile(self, username: str) -> User:

print(f"Attempting to view profile for '{username}'...")

user = self.user_repository.get_by_username(username)

if user:

print(f"Profile for '{username}': {user}")

else:

print(f"Profile for '{username}' not found.")

return user

print("\n--- LSP Good Example ---")

# Scenario 1: Registering a user with a writable repository

print("\n--- Using InMemoryUserRepository for registration ---")

in_memory_repo_lsp_c = InMemoryUserRepository()

reg_service_correct = UserRegistrationServiceLSPCorrect(in_memory_repo_lsp_c)

user_reg_successful = reg_service_correct.register_user("harry_lsp", "lsp_pass_correct", "harry@example.com")

if in_memory_repo_lsp_c.get_by_username("harry_lsp"):

print("Harry was successfully registered (as expected).")

else:

print("Harry was NOT registered (unexpected - error in setup).")

# Scenario 2: Viewing profiles with a readable repository (InMemory)

print("\n--- Using InMemoryUserRepository for viewing ---")

profile_viewer_in_memory = UserProfileViewerLSPCorrect(in_memory_repo_lsp_c)

profile_viewer_in_memory.view_user_profile("harry_lsp")

profile_viewer_in_memory.view_user_profile("non_existent_user")

# Scenario 3: Viewing profiles with a readable repository (Guest)

print("\n--- Using GuestUserRepository for viewing ---")

guest_repo_lsp_c = GuestUserRepository()

profile_viewer_guest = UserProfileViewerLSPCorrect(guest_repo_lsp_c)

profile_viewer_guest.view_user_profile("guest1")

profile_viewer_guest.view_user_profile("new_guest") # This guest user was not registered via GuestUserRepository

# Attempting to use GuestUserRepository for registration (will cause a TypeError at runtime, which is good!)

print("\n--- Attempting to register with GuestUserRepository (Expected TypeError) ---")

try:

reg_service_bad_attempt = UserRegistrationServiceLSPCorrect(guest_repo_lsp_c)

reg_service_bad_attempt.register_user("will_fail", "pass", "fail@example.com")

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Caught expected TypeError: {e}")

print("This demonstrates that the type system prevents using GuestUserRepository where a writable one is expected.")

print("\n--- End LSP Good Example ---\n")

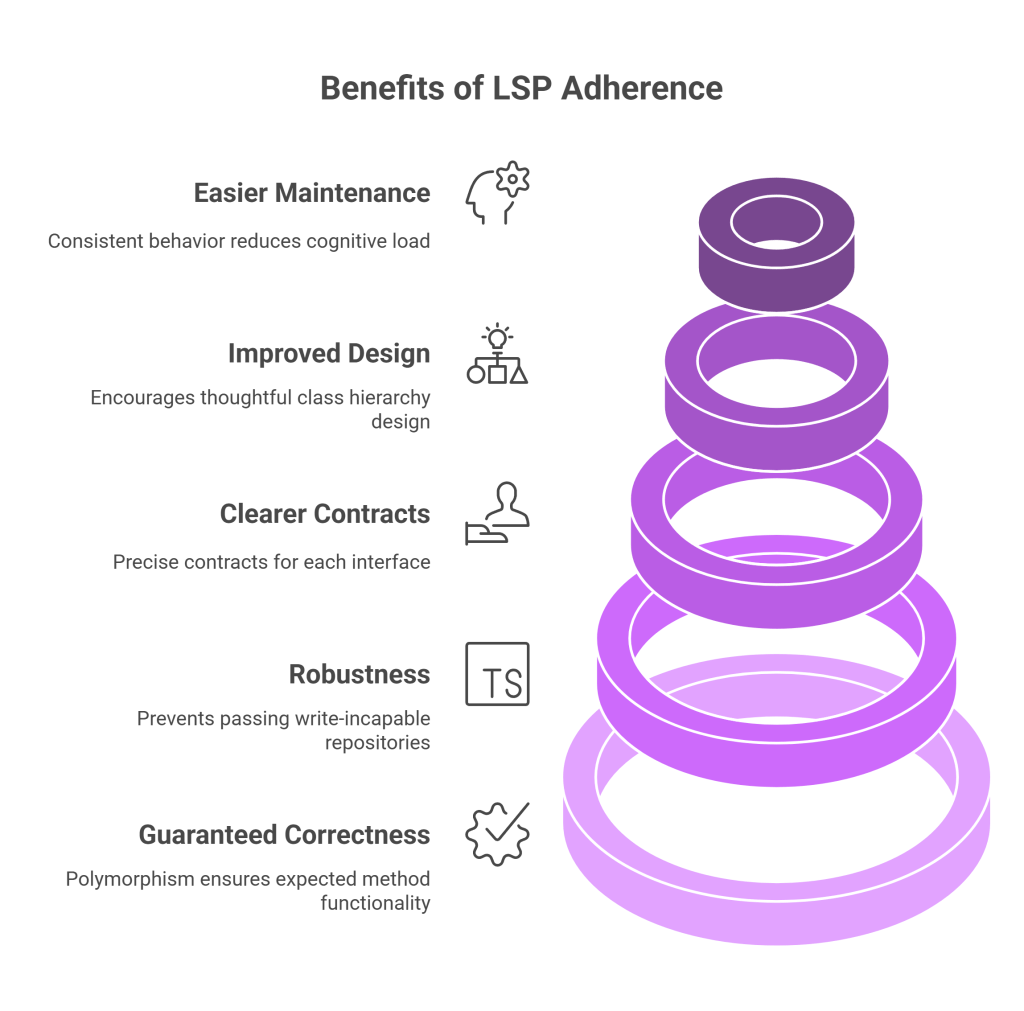

Benefits of Adhering to LSP

By segregating the IUserRepository into IUserReadableRepository and IUserWritableRepository and ensuring GuestUserRepository only implements the interface it can fully support, we gain the following benefits:

- Guaranteed Correctness through Polymorphism: When client code (

UserRegistrationServiceLSPCorrect) expects anIUserWritableRepository, it knows that thesavemethod will function as expected. There’s no surprise behavior or silent failures. Similarly,UserProfileViewerLSPCorrectcan confidently use anyIUserReadableRepository. - Robustness: The system becomes more robust because it’s impossible to accidentally pass a

GuestUserRepositoryto a component that requires write capabilities. Python’s type hinting and runtime checks (though not strict compile-time checks like in Java) will catch this mismatch early, preventing runtime errors related to unexpected behavior. - Clearer Contracts: Each interface (

IUserReadableRepository,IUserWritableRepository) has a very clear and precise contract. Implementations are only responsible for fulfilling the methods defined in the interfaces they choose to implement. - Improved Design: LSP encourages careful thought about class hierarchies and interface design. If a subclass cannot fulfill the contract of its superclass, it’s often a sign that the hierarchy is incorrect or the interface is too broad.

- Easier to Understand and Maintain: Developers can trust that when they use an object conforming to an interface, it will behave consistently with that interface’s contract. This reduces cognitive load and makes the codebase easier to understand and maintain.

LSP is crucial for building reliable and predictable systems that leverage polymorphism effectively. It ensures that extensions to your system don’t inadvertently break existing functionality.

4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) states:

“Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use. Rather than one large interface, many smaller, client-specific interfaces are better.”

This principle is closely related to SRP and LSP. While SRP focuses on a class having a single responsibility, ISP focuses on interfaces (or Abstract Base Classes in Python) being granular. If an interface contains methods that some of its implementers don’t need or cannot implement meaningfully, it’s a “fat” interface, and it violates ISP. This forces clients to depend on methods they don’t care about, leading to unnecessary coupling and potential LSP violations.

We already touched upon ISP when resolving the LSP violation. Now, let’s explicitly demonstrate a “fat” interface and then apply ISP.

The Problem: A Fat IUserManagement Interface

Let’s imagine, before we thought about SRP or LSP, we tried to create a single, comprehensive interface for all user-related operations.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

import uuid

# Re-using User class definition from SRP example

class User:

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

# --- Bad Example: Violates Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) ---

class IFatUserManagement(ABC):

"""

A 'fat' interface for user management.

It contains methods that not all clients or implementers will need.

"""

@abstractmethod

def create_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str) -> User:

"""Creates a new user account."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_user_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

"""Retrieves a user by ID."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def update_user_profile(self, user_id: str, new_email: str = None, new_username: str = None) -> User:

"""Updates a user's profile information."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def delete_user(self, user_id: str):

"""Deletes a user account."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def generate_user_report(self, start_date, end_date) -> dict:

"""Generates a report of user activity/stats."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def send_promotional_email(self, user_id: str, message: str):

"""Sends a promotional email to a specific user."""

pass

# Imagine an InMemoryUserManagement implementing this fat interface

class InMemoryFatUserManagement(IFatUserManagement):

_users = {} # {user_id: user_object}

def create_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str) -> User:

user = User(username, email=email)

user.password_hash = password_hash

self._users[user.user_id] = user

print(f"Fat Repo: Created user {username}")

return user

def get_user_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

print(f"Fat Repo: Getting user {user_id}")

return self._users.get(user_id)

def update_user_profile(self, user_id: str, new_email: str = None, new_username: str = None) -> User:

user = self._users.get(user_id)

if not user:

return None

if new_email:

user.email = new_email

if new_username:

user.username = new_username

print(f"Fat Repo: Updated user {user_id}")

return user

def delete_user(self, user_id: str):

if user_id in self._users:

del self._users[user_id]

print(f"Fat Repo: Deleted user {user_id}")

else:

print(f"Fat Repo: User {user_id} not found for deletion.")

def generate_user_report(self, start_date, end_date) -> dict:

"""

This method might be complex and require specific reporting tools.

For a simple in-memory implementation, it's just a placeholder.

"""

print(f"Fat Repo: Generating user report from {start_date} to {end_date} (simulated).")

return {"total_users": len(self._users), "active_users": len(self._users)}

def send_promotional_email(self, user_id: str, message: str):

"""

This method might require an email service integration.

For a simple in-memory implementation, it's just a placeholder.

"""

user = self._users.get(user_id)

if user and user.email:

print(f"Fat Repo: Sending promotional email to {user.email}: '{message}' (simulated).")

else:

print(f"Fat Repo: Cannot send promotional email to user {user_id} (email not found or user not found).")

# Client 1: User Registration Service (only needs create_user)

class UserRegistrationClientISP:

def __init__(self, user_manager: IFatUserManagement):

self.user_manager = user_manager

def register_new_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str):

print(f"ISP Client: Registering {username}...")

return self.user_manager.create_user(username, password_hash, email)

# Client 2: Admin Reporting Service (only needs generate_user_report)

class AdminReportingClientISP:

def __init__(self, user_manager: IFatUserManagement):

self.user_manager = user_manager

def get_monthly_report(self):

print("ISP Client: Getting monthly report...")

return self.user_manager.generate_user_report("2024-01-01", "2024-01-31")

print("--- ISP Bad Example ---")

fat_user_manager = InMemoryFatUserManagement()

# Client 1 uses the fat interface, but only needs `create_user`

reg_client = UserRegistrationClientISP(fat_user_manager)

new_user_isp = reg_client.register_new_user("ian_isp", "hash_ian", "ian@example.com")

# Client 2 uses the fat interface, but only needs `generate_user_report`

admin_client = AdminReportingClientISP(fat_user_manager)

report = admin_client.get_monthly_report()

print(f"Report: {report}")

# If we had a "GuestUserManagement" that only supports reading,

# it would be forced to implement `create_user`, `delete_user`, `generate_user_report`, etc.,

# even if it just raises `NotImplementedError` or does nothing, which is an LSP violation.

print("\n--- End ISP Bad Example ---\n")

Why It’s Bad: Violating ISP

The IFatUserManagement interface is problematic because:

- Forced Dependencies:

UserRegistrationClientISPonly needscreate_user, but it’s forced to depend onIFatUserManagement, which includes methods likegenerate_user_reportandsend_promotional_emailthat it doesn’t use. This creates unnecessary compile-time (or type-checking) dependencies. - Bloated Implementations: Any class implementing

IFatUserManagement(likeInMemoryFatUserManagement) must provide implementations for all methods, even if some are irrelevant or impossible for a specific context. For instance, a read-only user manager would have to implementcreate_useranddelete_useras no-ops or raise errors, leading to LSP violations. - Reduced Flexibility: It’s harder to create specialized implementations. If you want a

ReportingUserManagementthat only handles reports, it still has to implement all the CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) methods. - Increased Coupling: Clients are coupled to a larger interface than they need, making the system less modular and harder to refactor. A change to an unused method in

IFatUserManagementcould theoretically affect clients that don’t even use that method (e.g., if the method signature changes).

ISP advocates for “role interfaces” – interfaces that are tailored to the specific needs of a client or a role within the system.

The Solution: Segregating Interfaces

To adhere to ISP, we break down the IFatUserManagement interface into smaller, more focused interfaces, each representing a specific capability or role.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

import uuid

# Re-using User class definition from SRP example

class User:

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

# --- Correct Example: Adheres to Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) ---

# 1. Segregated Interfaces (Client-specific roles)

class IUserCreator(ABC):

"""Interface for creating users."""

@abstractmethod

def create_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str) -> User:

pass

class IUserReader(ABC):

"""Interface for reading/retrieving users."""

@abstractmethod

def get_user_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

pass

@abstractmethod

def get_user_by_username(self, username: str) -> User: # Added for completeness

pass

class IUserUpdater(ABC):

"""Interface for updating user profiles."""

@abstractmethod

def update_user_profile(self, user_id: str, new_email: str = None, new_username: str = None) -> User:

pass

class IUserDeleter(ABC):

"""Interface for deleting users."""

@abstractmethod

def delete_user(self, user_id: str):

pass

class IUserReporter(ABC):

"""Interface for generating user reports."""

@abstractmethod

def generate_user_report(self, start_date, end_date) -> dict:

pass

class IEmailSender(ABC):

"""Interface for sending emails to users."""

@abstractmethod

def send_promotional_email(self, user_id: str, message: str):

pass

# 2. Concrete Implementation: A comprehensive User Management (implements multiple interfaces)

class ComprehensiveUserManagement(IUserCreator, IUserReader, IUserUpdater, IUserDeleter, IUserReporter, IEmailSender):

_users = {} # {user_id: user_object}

def create_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str) -> User:

user = User(username, email=email)

user.password_hash = password_hash

self._users[user.user_id] = user

print(f"Comprehensive: Created user {username}")

return user

def get_user_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

print(f"Comprehensive: Getting user by ID {user_id}")

return self._users.get(user_id)

def get_user_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

print(f"Comprehensive: Getting user by username {username}")

for user in self._users.values():

if user.username == username:

return user

return None

def update_user_profile(self, user_id: str, new_email: str = None, new_username: str = None) -> User:

user = self._users.get(user_id)

if not user:

return None

if new_email:

user.email = new_email

if new_username:

user.username = new_username

print(f"Comprehensive: Updated user {user_id}")

return user

def delete_user(self, user_id: str):

if user_id in self._users:

del self._users[user_id]

print(f"Comprehensive: Deleted user {user_id}")

else:

print(f"Comprehensive: User {user_id} not found for deletion.")

def generate_user_report(self, start_date, end_date) -> dict:

print(f"Comprehensive: Generating user report from {start_date} to {end_date} (simulated).")

return {"total_users": len(self._users), "active_users": len(self._users)}

def send_promotional_email(self, user_id: str, message: str):

user = self._users.get(user_id)

if user and user.email:

print(f"Comprehensive: Sending promotional email to {user.email}: '{message}' (simulated).")

else:

print(f"Comprehensive: Cannot send promotional email to user {user_id} (email not found or user not found).")

# 3. Client code now depends on the specific, smaller interfaces they need

class UserRegistrationClientISPCorrect:

def __init__(self, user_creator: IUserCreator):

self.user_creator = user_creator

def register_new_user(self, username: str, password_hash: str, email: str):

print(f"ISP Correct Client: Registering {username}...")

return self.user_creator.create_user(username, password_hash, email)

class AdminReportingClientISPCorrect:

def __init__(self, user_reporter: IUserReporter):

self.user_reporter = user_reporter

def get_monthly_report(self):

print("ISP Correct Client: Getting monthly report...")

return self.user_reporter.generate_user_report("2024-01-01", "2024-01-31")

# Example of a read-only user service (e.g., for public profile viewing)

class PublicProfileService:

def __init__(self, user_reader: IUserReader):

self.user_reader = user_reader

def display_profile(self, user_id: str):

user = self.user_reader.get_user_by_id(user_id)

if user:

print(f"Public Profile: Username: {user.username}, Email: {user.email}")

else:

print(f"Public Profile: User with ID {user_id} not found.")

print("\n--- ISP Good Example ---")

comprehensive_manager = ComprehensiveUserManagement()

# Client 1 uses only IUserCreator

reg_client_correct = UserRegistrationClientISPCorrect(comprehensive_manager)

new_user_isp_c = reg_client_correct.register_new_user("john_isp", "hash_john", "john@example.com")

# Client 2 uses only IUserReporter

admin_client_correct = AdminReportingClientISPCorrect(comprehensive_manager)

report_c = admin_client_correct.get_monthly_report()

print(f"Report: {report_c}")

# A new service that only needs to read users

public_profile_service = PublicProfileService(comprehensive_manager)

if new_user_isp_c:

public_profile_service.display_profile(new_user_isp_c.user_id)

public_profile_service.display_profile("non_existent_id")

# We could also have a specific "ReadOnlyUserManagement" class that only implements IUserReader:

class ReadOnlyUserManagement(IUserReader):

_users = {} # This would typically be populated from a read-only data source

def __init__(self, initial_users: dict = None):

if initial_users:

self._users = initial_users

def get_user_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

print(f"Read-Only: Getting user by ID {user_id}")

return self._users.get(user_id)

def get_user_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

print(f"Read-Only: Getting user by username {username}")

for user in self._users.values():

if user.username == username:

return user

return None

print("\n--- Using ReadOnlyUserManagement with PublicProfileService ---")

read_only_users = {

"read_only_id_1": User("read_only_user_1", user_id="read_only_id_1", email="ro1@example.com"),

"read_only_id_2": User("read_only_user_2", user_id="read_only_id_2", email="ro2@example.com")

}

read_only_manager = ReadOnlyUserManagement(read_only_users)

public_profile_service_ro = PublicProfileService(read_only_manager)

public_profile_service_ro.display_profile("read_only_id_1")

public_profile_service_ro.display_profile("non_existent_id")

# Attempting to register with a read-only manager (will cause TypeError)

print("\n--- Attempting to register with ReadOnlyUserManagement (Expected TypeError) ---")

try:

reg_client_bad_attempt = UserRegistrationClientISPCorrect(read_only_manager)

reg_client_bad_attempt.register_new_user("fail_user", "pass", "fail@example.com")

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Caught expected TypeError: {e}")

print("This demonstrates that the type system prevents using ReadOnlyUserManagement where a creator is expected.")

print("\n--- End ISP Good Example ---\n")

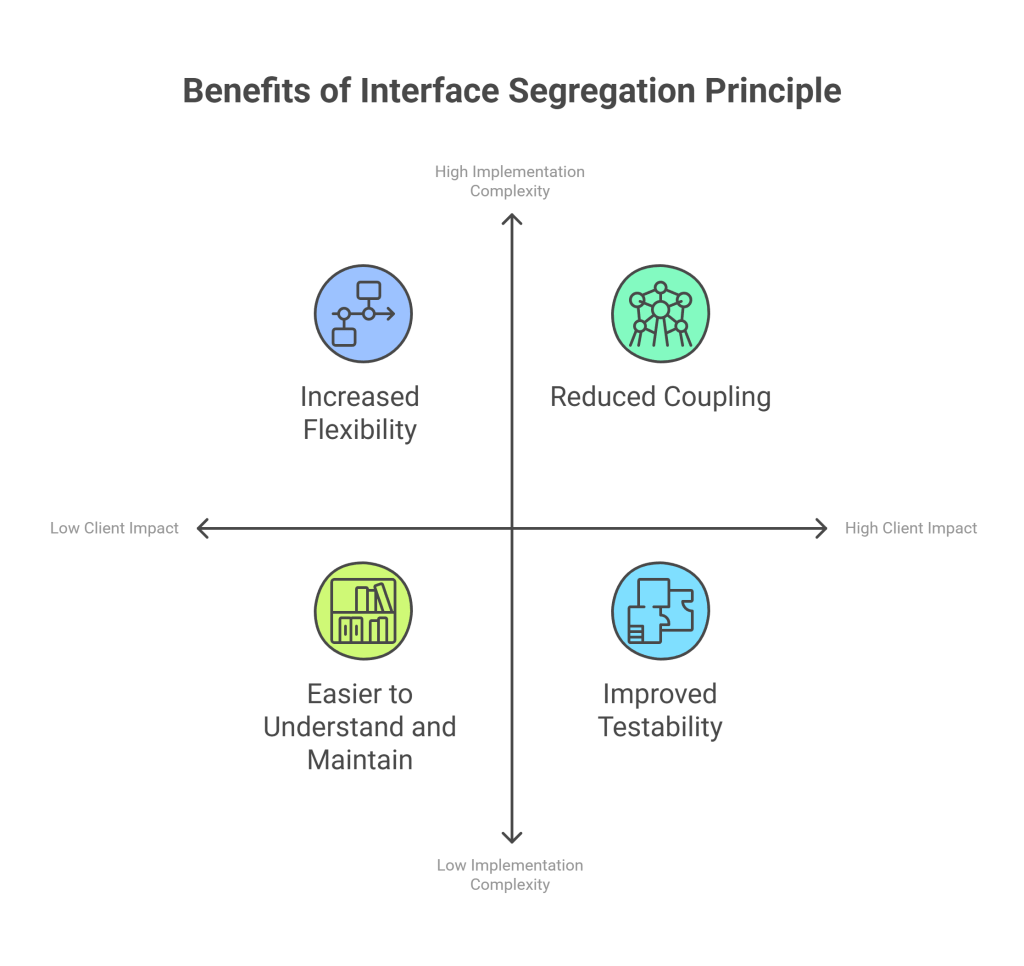

Benefits of Adhering to ISP

By breaking down the fat IFatUserManagement interface into smaller, client-specific interfaces, we achieve:

- Reduced Coupling: Clients (

UserRegistrationClientISPCorrect,AdminReportingClientISPCorrect,PublicProfileService) are now only coupled to the specific interfaces they actually use. They don’t need to know about or depend on methods irrelevant to their functionality. - Increased Flexibility: It’s much easier to create specialized implementations. For example,

ReadOnlyUserManagementcan exist without being forced to implement methods likecreate_userordelete_userthat are not applicable to its role. This also prevents LSP violations. - Easier to Understand and Maintain: Each interface has a clear, focused purpose, making the system’s design more transparent. When you see a class implementing

IUserCreator, you immediately know its primary role. - Improved Testability: Testing becomes simpler as you can easily mock or stub out only the necessary interfaces for a given client, rather than having to mock a large, complex interface.

- Prevents “Polluting” Clients: Clients are not “polluted” with methods they don’t need, leading to cleaner, more concise code within the client modules.

ISP encourages a design where interfaces are as small and focused as possible, leading to a more modular, flexible, and maintainable codebase. It’s a key principle for designing robust APIs and abstract layers.

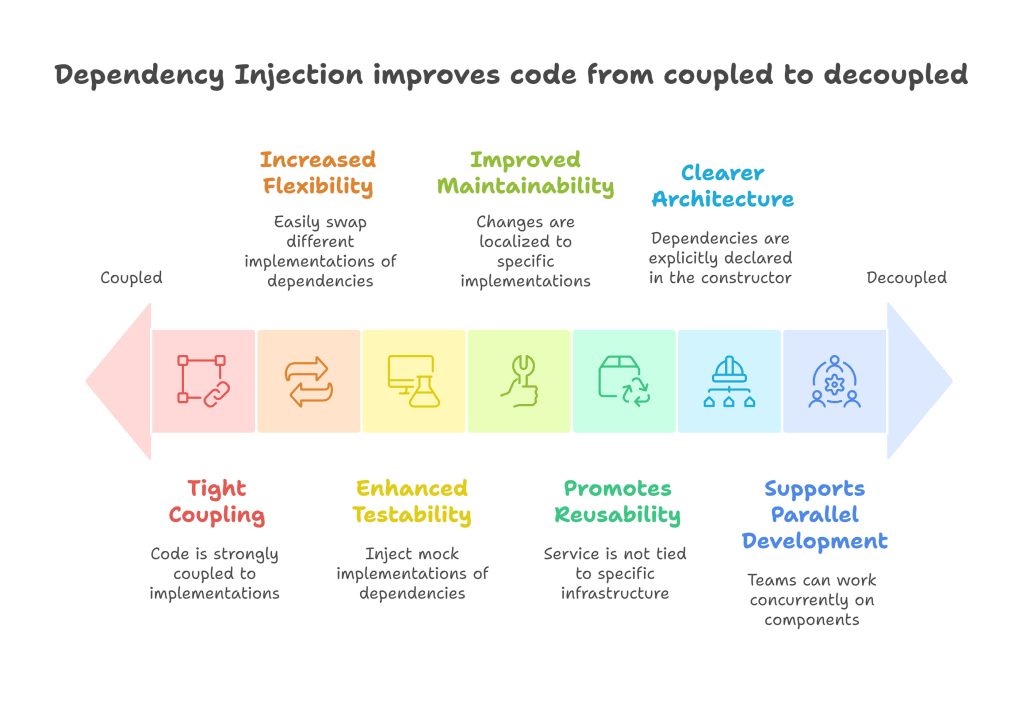

5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) is often considered the most advanced of the SOLID principles, and it’s fundamental to achieving highly decoupled and flexible architectures. It states:

“High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.”

“Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.”

In essence, DIP encourages us to invert the traditional flow of control. Instead of high-level modules (which contain important business logic) directly depending on concrete, low-level implementations (like specific database drivers or hashing algorithms), both should depend on abstractions (interfaces or abstract classes). This allows for greater flexibility, testability, and maintainability.

The Problem: Direct Concrete Dependencies

Let’s look back at our initial UserAccountService (from the SRP bad example, or even a slightly improved version that still directly instantiates its dependencies). If UserAccountService directly creates instances of PasswordHasher and InMemoryUserRepository inside its constructor or methods, it violates DIP.

import hashlib

import uuid

import os

import smtplib

from email.mime.text import MIMEText

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

# Re-using core classes and interfaces from previous examples for context

# User, IPasswordHasher, SHA256Hasher, BCryptHasher,

# IUserReadableRepository, IUserWritableRepository, InMemoryUserRepository, EmailNotifier

class User:

def __init__(self, username: str, user_id: str = None, email: str = None):

self.username = username

self.user_id = user_id if user_id else str(uuid.uuid4())

self.email = email

self.password_hash = None

def __repr__(self):

return f"User(id='{self.user_id}', username='{self.username}', email='{self.email}')"

class IPasswordHasher(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str: pass

@abstractmethod

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool: pass

class SHA256Hasher(IPasswordHasher):

def hash_password(self, password: str) -> str:

salt = os.urandom(16)

hashed_password = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return f"sha256:{salt.hex()}:{hashed_password}"

def verify_password(self, password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

try:

prefix, salt_hex, stored_hash_value = stored_hash.split(':')

if prefix != "sha256": return False

salt = bytes.fromhex(salt_hex)

input_hash = hashlib.sha256(salt + password.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest()

return input_hash == stored_hash_value

except ValueError: return False

class IUserWritableRepository(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str): pass

class IUserReadableRepository(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User: pass

@abstractmethod

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User: pass

class InMemoryUserRepository(IUserReadableRepository, IUserWritableRepository):

_simulated_db = {}

def save(self, user: User, password_hash: str):

self._simulated_db[user.user_id] = {"username": user.username, "password_hash": password_hash, "user_id": user.user_id, "email": user.email}

print(f"InMemoryRepo: Saved {user.username}")

def get_by_username(self, username: str) -> User:

for user_data in self._simulated_db.values():

if user_data["username"] == username:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

def get_by_id(self, user_id: str) -> User:

user_data = self._simulated_db.get(user_id)

if user_data:

user = User(user_data["username"], user_data["user_id"], user_data["email"])

user.password_hash = user_data["password_hash"]

return user

return None

class EmailNotifier:

def send_welcome_email(self, user: User):

if not user.email: return

print(f"EmailNotifier: Sending welcome email to {user.email} (simulated).")

# --- Bad Example: Violates Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) ---

class UserAccountServiceDIPBad:

"""

This high-level module directly depends on concrete low-level modules.

Violates DIP.

"""

def __init__(self):

# Direct instantiation of concrete low-level implementations

self.password_hasher = SHA256Hasher() # High-level depends on low-level concrete

self.user_repository = InMemoryUserRepository() # High-level depends on low-level concrete

self.email_notifier = EmailNotifier() # High-level depends on low-level concrete

print("UserAccountServiceDIPBad initialized with concrete dependencies.")

def register_user(self, username: str, password: str, email: str = None) -> User:

if self.user_repository.get_by_username(username):

print(f"Error: User '{username}' already exists (DIP Bad).")

return None

user = User(username, email=email)

hashed_password = self.password_hasher.hash_password(password)

self.user_repository.save(user, hashed_password)

user.password_hash = hashed_password

print(f"User '{username}' registered (DIP Bad).")

if email:

self.email_notifier.send_welcome_email(user)

return user

def authenticate_user(self, username: str, password: str) -> User:

user = self.user_repository.get_by_username(username)

if user and user.password_hash:

if self.password_hasher.verify_password(password, user.password_hash):

print(f"User '{username}' authenticated (DIP Bad).")

return user

print(f"Authentication failed for '{username}' (DIP Bad).")

return None