The proliferation of online platforms has brought with it a darker side: a surge in hate speech, toxicity, and online harassment. In response, the field of artificial intelligence has been tasked with an immense challenge: developing automated systems that can detect and moderate this harmful content at scale. These systems, powered by sophisticated machine learning models, are trained on vast datasets of online text that have been meticulously labeled by human annotators. However, a growing body of research reveals a critical flaw in this process, one that threatens the very fairness and effectiveness of these AI-powered gatekeepers: overfitting to annotator bias.

This article delves into the complex issue of annotator bias in hate speech and toxicity datasets. We will explore the multifaceted nature of this bias, dissect the mechanisms through which machine learning models learn and amplify it, and examine the far-reaching consequences of this overfitting. Finally, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge mitigation strategies being developed to create more equitable and accurate hate speech detection systems.

The Subjective Nature of Hate Speech and the Genesis of Annotator Bias

At the heart of the annotator bias problem lies a fundamental truth: hate speech is a deeply subjective and context-dependent phenomenon. What one person considers a hateful slur, another might see as reclaimed language. A statement that is innocuous in one cultural context can be deeply offensive in another. This inherent subjectivity makes the task of creating a universally agreed-upon definition of hate speech a near-impossibility.

When human annotators are tasked with labeling online content, they bring with them a lifetime of personal experiences, cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and, inevitably, biases. These biases, both conscious and unconscious, can significantly influence their judgments. The result is that the “ground truth” of our hate speech datasets is not an objective reality, but rather a reflection of the perspectives of the people who created it.

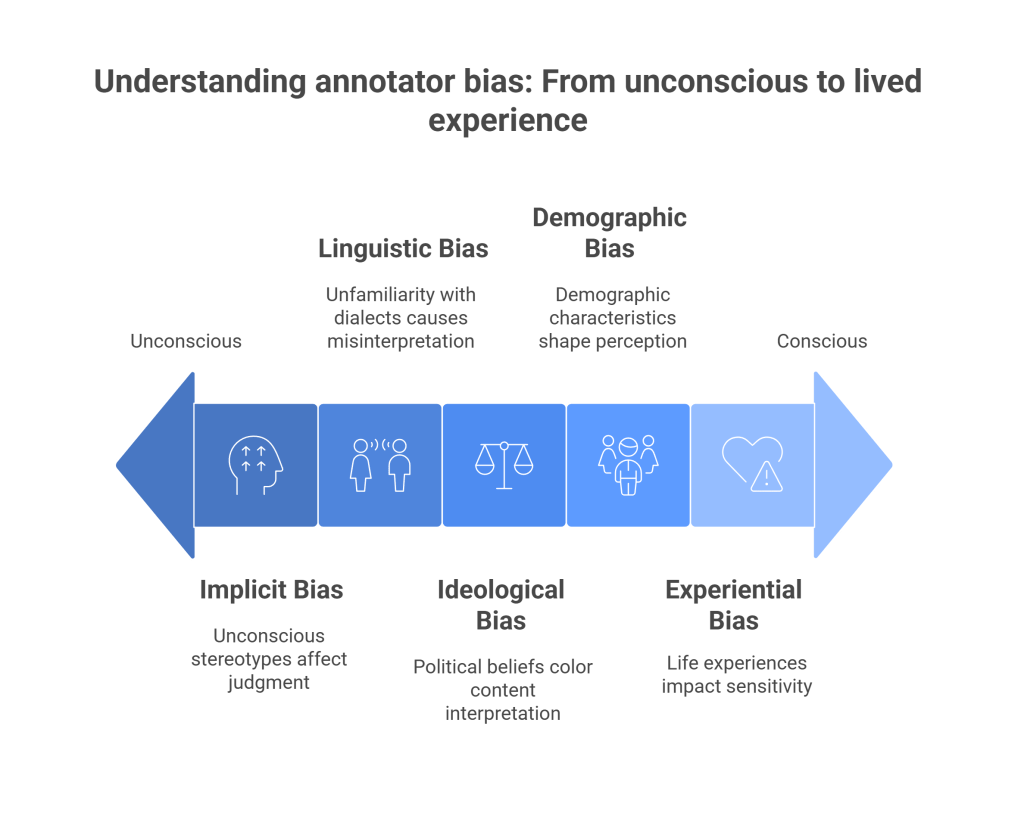

Annotator bias can manifest in several forms:

- Demographic Bias: An annotator’s race, gender, age, sexual orientation, and other demographic characteristics can shape their perception of what constitutes hate speech. For instance, a person from a marginalized group may be more attuned to subtle forms of discrimination and microaggressions that someone from a majority group might overlook. Conversely, an annotator may be less sensitive to hate speech directed at groups they do not belong to.

- Ideological and Political Bias: An annotator’s political leanings and ideological beliefs can color their interpretation of online content. A comment that is critical of a political figure might be labeled as toxic by a supporter of that figure, while an opponent might see it as legitimate political discourse.

- Linguistic Bias: Language is not monolithic, and different communities use it in different ways. Annotators who are unfamiliar with certain dialects, such as African American English (AAE), may misinterpret non-standard language as toxic or offensive. This can lead to the systematic penalization of content from specific linguistic communities.

- Positional and Experiential Bias: An individual’s life experiences, including whether they have been the target of online harassment, can significantly impact their sensitivity to harmful content. Those who have been personally affected by hate speech may have a lower threshold for what they consider toxic.

- Implicit Bias: These are the unconscious associations and stereotypes that everyone holds. Implicit biases can lead annotators to make snap judgments about content based on keywords or phrases, without fully considering the context. For example, the mere presence of an identity term, such as “Black” or “gay,” can trigger an implicit bias that leads an annotator to be more likely to label a comment as toxic, even if the comment itself is not hateful.

The problem is further compounded by the fact that the pool of annotators for many large-scale datasets is not always as diverse as the global population of internet users. This lack of diversity can lead to a narrow and unrepresentative “ground truth” that is then used to train models that are deployed to police the speech of billions.

How Machine Learning Models Overfit to Annotator Bias

Machine learning models, particularly the large language models (LLMs) that are now state-of-the-art in natural language processing, are incredibly powerful pattern-matching machines. When they are trained on hate speech datasets, they don’t just learn to identify hate speech; they also learn the subtle biases of the annotators who created the data. This is the process of overfitting, and it can have pernicious consequences.

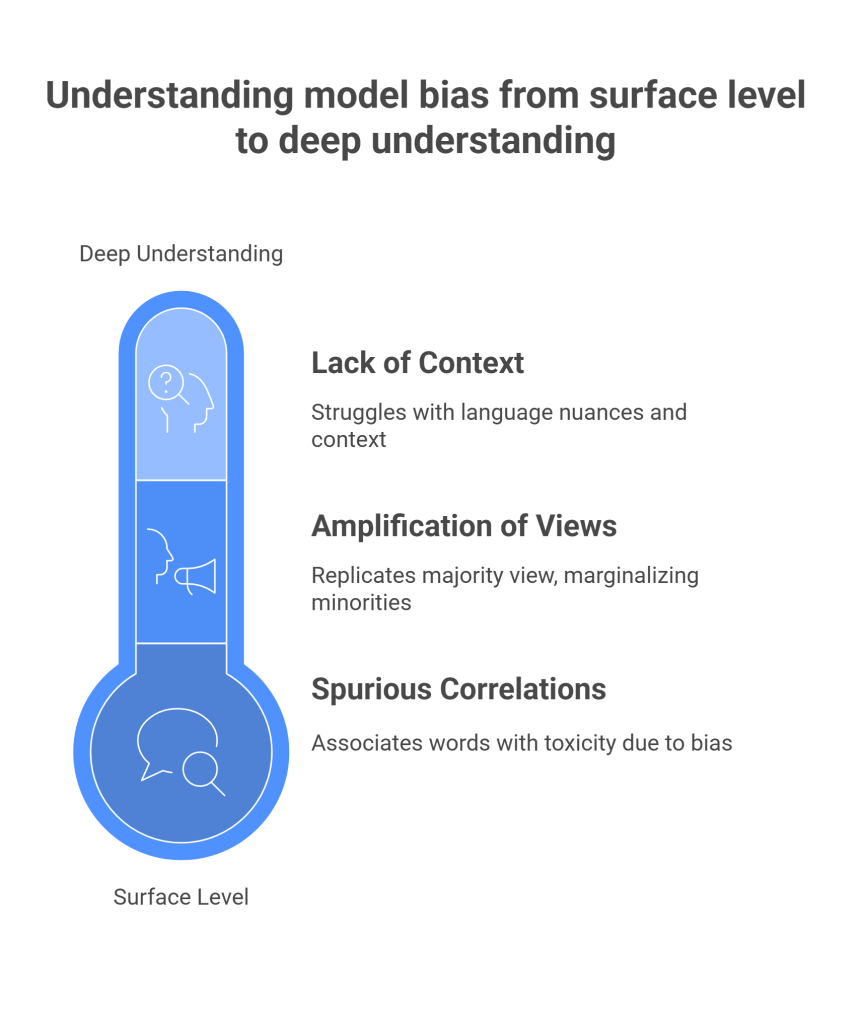

Overfitting to annotator bias occurs through several mechanisms:

- Spurious Correlations: Models often learn to associate certain words or phrases with toxicity, not because they are inherently hateful, but because they are more likely to appear in comments that have been labeled as toxic by biased annotators. For example, if a dataset has been annotated by individuals who are biased against a particular political ideology, the model may learn to associate the names of political figures or specific political terms with toxicity.

- Amplification of Majority Views: In datasets where there is disagreement among annotators, the majority opinion is often taken as the “ground truth.” This can lead to the marginalization of minority perspectives and the amplification of the biases of the dominant group of annotators. A model trained on such data will learn to replicate the majority view, even if it is biased.

- Lack of Contextual Understanding: While LLMs are becoming increasingly sophisticated, they still struggle with the nuances of human language and context. A model may not be able to distinguish between a genuine slur and the use of the same word in a reclaimed or satirical context. If the training data does not adequately represent these different contexts, the model will be more likely to make errors.

The result of this overfitting is that our hate speech detection models are not just identifying hate speech; they are also learning to replicate the biases of the humans who trained them. This can lead to a host of negative consequences.

The Far-Reaching Consequences of Overfitting

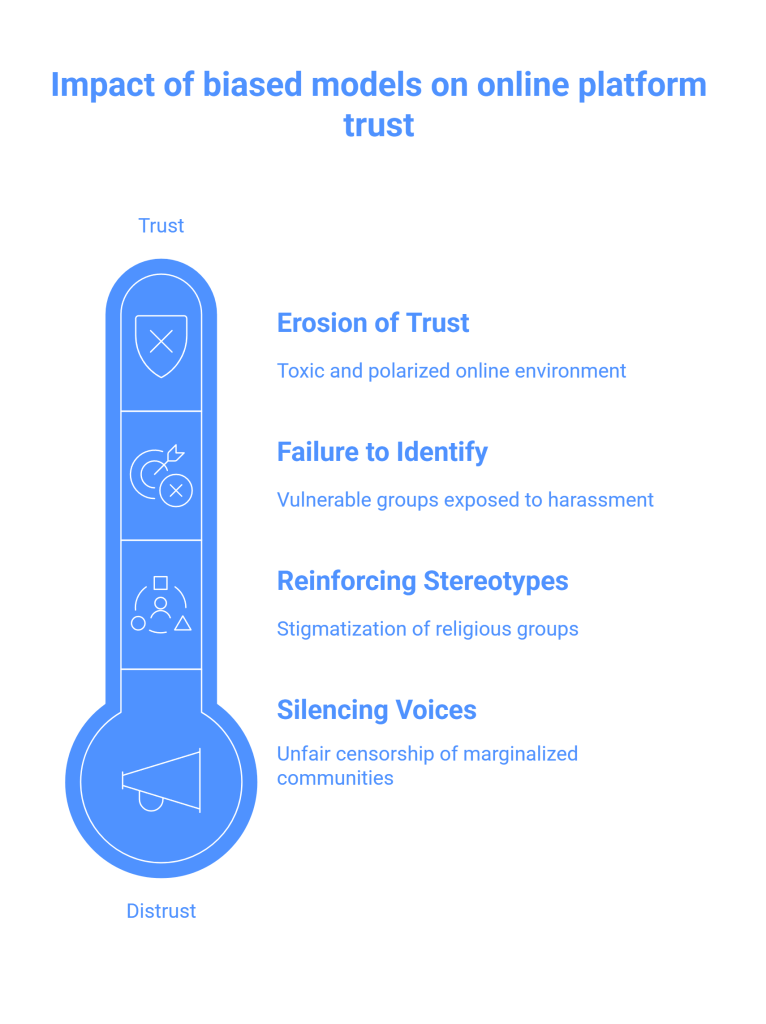

The overfitting of hate speech detection models to annotator bias is not just a technical problem; it has real-world consequences that can disproportionately harm already marginalized communities.

- Silencing of Marginalized Voices: When models are biased against certain dialects or identity terms, they are more likely to flag content from individuals who use that language. This can lead to the unfair censorship of marginalized communities, who may find their posts and accounts being taken down for no legitimate reason. For example, research has shown that models are more likely to flag tweets written in African American English as toxic, even when the content is not hateful.

- Failure to Identify Genuine Hate Speech: Conversely, if a model has been trained on data that is not sensitive to certain forms of hate speech, it may fail to identify and remove genuinely harmful content. This can leave vulnerable individuals and groups exposed to online harassment.

- Reinforcement of Stereotypes: By learning and replicating the biases of annotators, hate speech detection models can inadvertently reinforce harmful stereotypes. For example, if a model learns to associate the name of a particular religious group with toxicity, it can contribute to the stigmatization of that group.

- Erosion of Trust in Online Platforms: When users feel that they are being unfairly censored or that platforms are not doing enough to protect them from harassment, it can erode their trust in those platforms. This can lead to a more toxic and polarized online environment.

In short, the overfitting of hate speech detection models to annotator bias can create a vicious cycle in which the very tools that are designed to make the internet a safer place end up perpetuating the same harms they are meant to prevent.

Mitigation Strategies: Towards More Equitable Hate Speech Detection

Recognizing the gravity of this problem, researchers and practitioners have been working to develop a range of mitigation strategies. These strategies can be broadly categorized into three groups: data-centric, model-centric, and human-in-the-loop approaches.

Data-Centric Approaches

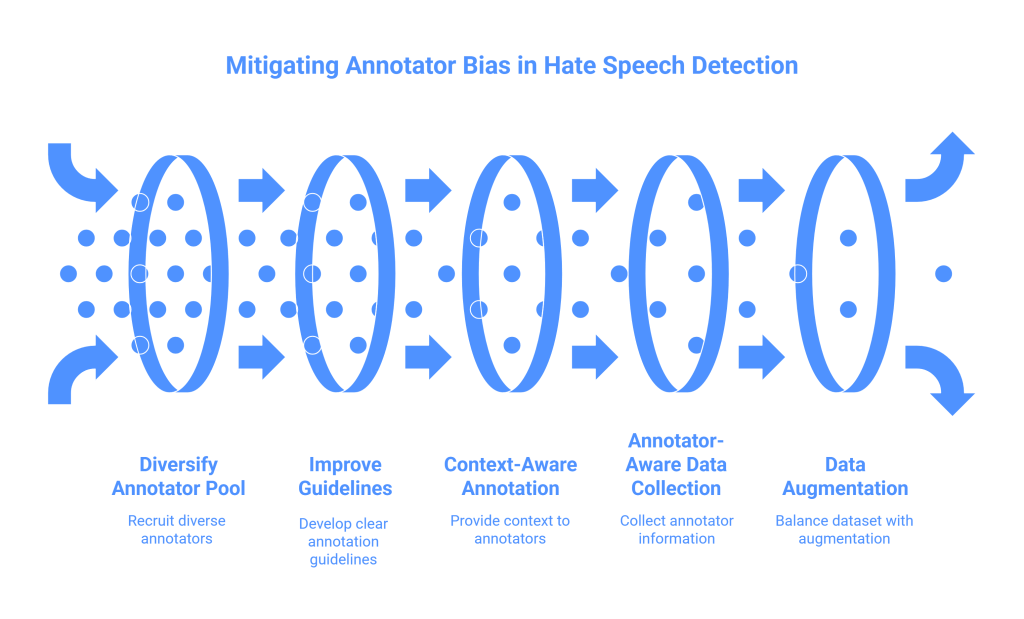

Data-centric approaches focus on improving the quality and fairness of the training data itself.

- Diversifying the Annotator Pool: One of the most important steps in mitigating annotator bias is to ensure that the pool of annotators is as diverse as the population of internet users. This means actively recruiting annotators from a wide range of demographic, ideological, and linguistic backgrounds.

- Improving Annotation Guidelines: Clear and comprehensive annotation guidelines are essential for reducing subjectivity and ensuring consistency. These guidelines should provide annotators with a clear definition of what constitutes hate speech, as well as examples of edge cases and ambiguous content.

- Context-Aware Annotation: Annotators should be provided with as much context as possible when they are labeling content. This includes information about the author of the content, the platform on which it was posted, and the broader conversation in which it appeared.

- Annotator-Aware Data Collection: Instead of simply collecting labels, some researchers are now advocating for collecting information about the annotators themselves. This can allow for a more nuanced understanding of how different groups perceive hate speech and can be used to create more fair and representative datasets.

- Data Augmentation and Re-weighting: These techniques can be used to create more balanced datasets. For example, if a dataset is found to be biased against a particular dialect, data augmentation can be used to generate more examples of non-toxic content in that dialect. Data re-weighting can be used to give more weight to examples from underrepresented groups during the training process.

Model-Centric Approaches

Model-centric approaches focus on developing machine learning models that are more robust to annotator bias.

- Adversarial Training: In this approach, a second “adversarial” model is trained to identify and exploit the biases of the primary hate speech detection model. The primary model is then retrained to be more robust to these attacks.

- Invariant Rationalization: This technique aims to force the model to focus on the truly hateful aspects of a text, rather than on spurious correlations. It does this by identifying a “rationale” for the model’s decision and then ensuring that this rationale is invariant to changes in non-hateful aspects of the text.

- Multi-Task Learning: In this approach, the model is trained to perform multiple tasks at once, such as identifying both the toxicity of a comment and the identity of the group it is targeting. This can help the model to develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between language and hate speech.

- Causal Inference: Some researchers are exploring the use of causal inference techniques to disentangle the causal relationship between language, hate speech, and annotator bias. This can help to identify and remove the spurious correlations that are at the root of many bias problems.

Human-in-the-Loop Approaches

Human-in-the-loop approaches recognize that automated systems are not perfect and that human oversight is still essential.

- Appeal Mechanisms: Users should have the right to appeal decisions made by automated hate speech detection systems. These appeals should be reviewed by human moderators who are trained to be sensitive to the nuances of language and context.

- Active Learning: In this approach, the model is designed to identify the most ambiguous or difficult-to-classify content and then send it to human annotators for review. This can help to improve the quality of the training data over time.

- Explainable AI (XAI): XAI techniques can be used to make the decisions of hate speech detection models more transparent and understandable. This can help users to understand why their content was flagged and can also help researchers to identify and correct biases in the model.

The Double-Edged Sword of Large Language Models

The rise of large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 has introduced a new dimension to the problem of annotator bias. On the one hand, LLMs can be used as powerful tools for data annotation, potentially reducing the time and cost of creating large-scale datasets. On the other hand, LLMs are themselves trained on vast amounts of text from the internet, and they can inherit and amplify the biases that are present in that data.

Recent research has shown that LLMs can exhibit many of the same biases as human annotators, including demographic, ideological, and linguistic biases. This raises concerns about the use of LLMs as a replacement for human annotators.

However, LLMs also offer new opportunities for mitigating bias. For example, they can be used to:

- Generate synthetic data to create more balanced and representative datasets.

- Identify and flag potential biases in existing datasets.

- Provide annotators with additional context and information to help them make more informed decisions.

- Power more sophisticated and context-aware hate speech detection models.

The key to harnessing the power of LLMs for good is to be aware of their limitations and to use them in a responsible and ethical manner.

Conclusion: A Call for a More Holistic Approach

The problem of overfitting to annotator bias in hate speech and toxicity datasets is a complex and multifaceted one, and there is no single, easy solution. Addressing this challenge will require a holistic approach that combines data-centric, model-centric, and human-in-the-loop strategies.

We must move beyond a simplistic view of hate speech detection as a purely technical problem and recognize that it is also a deeply social and ethical one. This means:

- Investing in the creation of more diverse and representative datasets.

- Developing more robust and fair machine learning models.

- Empowering users with more control over their online experiences.

- Fostering a more critical and nuanced conversation about the role of AI in content moderation.

Ultimately, the goal is not to create a perfect, unbiased hate speech detection system—such a thing may not even be possible. Rather, the goal is to create systems that are as fair, transparent, and accountable as possible, and that are designed to protect the most vulnerable members of our online communities. The path forward is challenging, but by working together, we can build a more equitable and inclusive digital world.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.