Introduction

One of the most anxiety-inducing aspects of transitioning into a team leadership role is the inevitability of difficult conversations. Whether you’re addressing missed deadlines, behavioral issues, performance concerns, or delivering unwelcome organizational decisions, these moments can make or break your relationship with your team members and your credibility as a leader.

The greatest fear many new leaders harbor is that after delivering a difficult message, the team member will leave feeling demoralized, resentful, or convinced that you’re a poor manager. This fear often leads to two equally problematic responses: avoiding the conversation entirely or delivering it so harshly that the fear becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The truth is that difficult conversations, when handled skillfully, can actually strengthen your relationship with team members and enhance their respect for you as a leader. The key lies not in softening the message or avoiding accountability, but in how you frame, deliver, and conclude these conversations. This guide will walk you through a comprehensive approach that maintains both performance standards and positive relationships.

Understanding the Paradox: Clarity with Compassion

Before diving into tactics, you must internalize a fundamental leadership paradox: the most compassionate thing you can do for struggling team members is to be clear and direct about problems, not to shield them from difficult truths.

When you avoid tough conversations to “be nice,” you’re actually being unkind. You’re denying someone the opportunity to improve, potentially setting them up for more serious consequences later, and creating uncertainty that breeds anxiety. Team members generally prefer a manager who addresses issues directly over one who seems friendly but allows problems to fester.

However, being direct doesn’t mean being harsh. The goal is to combine absolute clarity about the issue with genuine care for the person. This isn’t about choosing between being liked and being respected; skilled leaders earn both by demonstrating that they care enough to have hard conversations in service of their team members’ growth and success.

The Foundation: Mindset Matters More Than Script

Your internal state before and during a difficult conversation matters enormously. Team members are remarkably perceptive; they can sense whether you’re approaching them as an adversary to defeat, an obstacle to manage, or a valued colleague you’re invested in helping succeed.

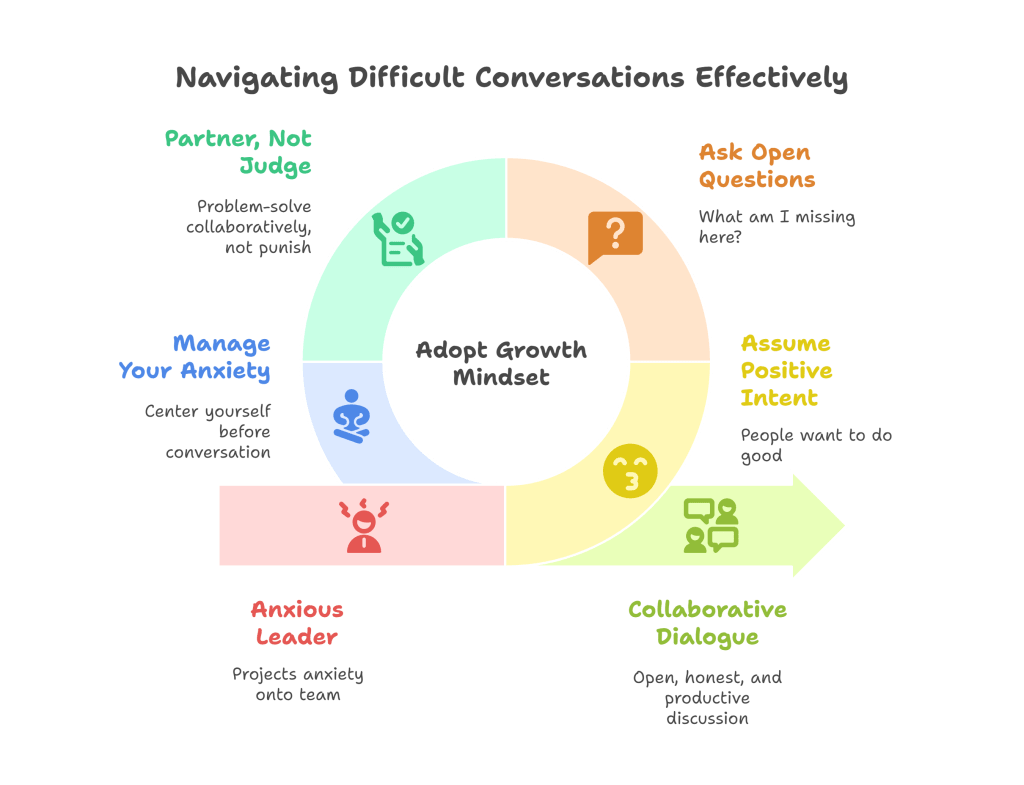

Adopt a Growth-Oriented Mindset

Enter every difficult conversation believing that people generally want to do good work and that most performance or behavior issues stem from unclear expectations, insufficient resources, skill gaps, or external factors rather than character flaws or malicious intent. This assumption of positive intent dramatically changes your tone and approach.

Ask yourself before the conversation: “What might I be missing? What circumstances could explain this situation that I’m unaware of?” This curiosity prevents you from arriving with a fixed narrative and opens space for genuine dialogue.

See Yourself as a Partner, Not a Judge

Your role isn’t to pronounce judgment but to problem-solve collaboratively. You’re not there to punish or humiliate; you’re there to identify an issue, understand it fully, and work together to resolve it. When you shift from a judge mentality to a partner mentality, your body language, word choice, and tone naturally become more collaborative and less adversarial.

Manage Your Own Anxiety

New leaders often project their anxiety onto team members, assuming the conversation will be devastating for the other person. Often, the team member already knows something isn’t working and may even feel relieved to finally discuss it openly. Your nervous energy can actually make the conversation more uncomfortable than the content itself.

Take time before difficult conversations to center yourself. Remind yourself that having this conversation is part of serving your team member well, not an attack on them. If you believe in the value of what you’re doing, that confidence will come through.

Preparation: The Conversation Before the Conversation

Inadequate preparation is one of the primary reasons difficult conversations go sideways. When you’re unprepared, you’re more likely to become flustered, say things you don’t mean, or fail to communicate clearly.

Define Your Purpose with Precision

What specifically do you need to address? Write it down in one or two sentences. Vague concerns like “attitude problem” or “not a team player” need to be translated into specific, observable behaviors or measurable outcomes.

For example:

- Vague: “You need to be more professional”

- Specific: “I need to discuss the impact of frequently arriving 20-30 minutes late to team meetings”

Gather Concrete Examples

Nothing derails a difficult conversation faster than making broad accusations without evidence. Prepare at least two or three specific instances that illustrate the issue, including dates, situations, and impacts.

Good examples are factual and observable: “On March 15th, the client presentation was submitted two hours after the deadline, which meant the client couldn’t review it before their board meeting” is far more effective than “You’re always missing deadlines.”

Anticipate Their Perspective

Spend time genuinely considering how the situation might look from their viewpoint. What valid reasons might exist for their behavior? What systemic issues might be contributing? What might you, as their leader, have done or failed to do that contributed to this situation?

This isn’t about excusing performance issues, but about entering the conversation with intellectual humility and genuine curiosity. When you can articulate their perspective fairly, even if you still need to address the issue, it demonstrates respect and often diffuses defensiveness.

Clarify the Desired Outcome

What does success look like at the end of this conversation? Usually, it involves:

- The team member clearly understanding the issue and its impact

- Both parties agreeing on specific next steps or changes

- The relationship remaining intact or even strengthened

- The team member feeling respected even if they don’t agree with everything

Having clarity on your desired outcome helps you navigate the conversation if it goes off track.

Setting the Stage: The Opening Matters

The first 30 seconds of a difficult conversation set the tone for everything that follows. This is where many leaders make critical errors, either being so indirect that the message gets lost or so abrupt that the team member becomes immediately defensive.

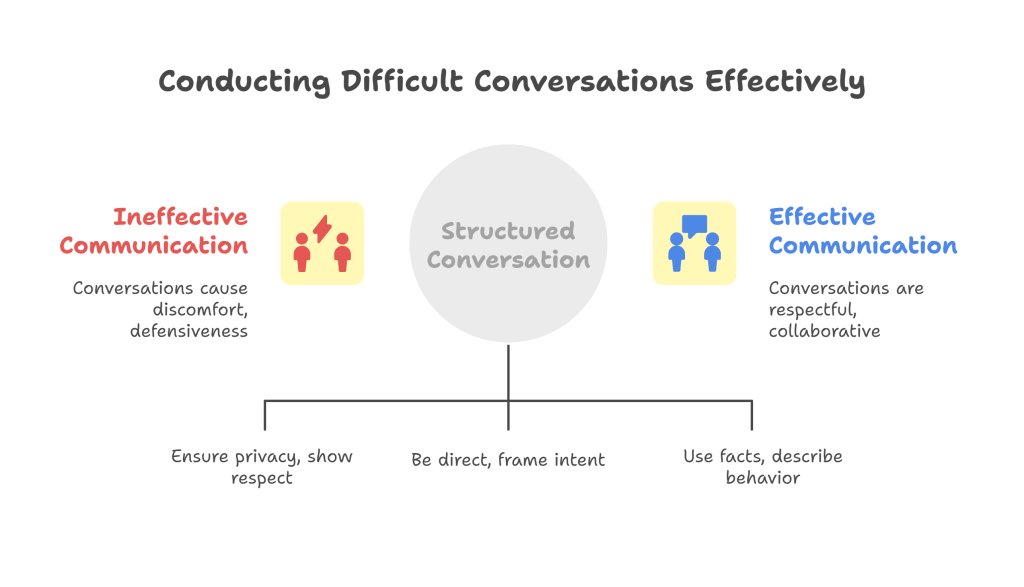

Choose the Right Environment

Privacy is non-negotiable. Have the conversation in a closed-door office, a quiet meeting room, or via video call if remote, never in open spaces where others can overhear. This shows respect and prevents embarrassment that can trigger defensiveness.

Timing matters too. Avoid having difficult conversations late on Friday afternoons when people will stew over the weekend, or right before major presentations when they need to be focused. Give some advance notice when possible: “I’d like to schedule 30 minutes to discuss the Q2 project. Does Tuesday at 2pm work?”

This advance notice serves two purposes: it prevents catching someone completely off-guard, and it signals that this is important enough to dedicate focused time.

Open with Respectful Directness

Avoid the instinct to engage in extensive small talk before dropping the difficult topic. This creates anxiety and can feel manipulative. Instead, after a brief greeting, transition clearly:

“Thanks for making time to meet. I want to discuss something that’s important, and I know this conversation might be uncomfortable. I’m bringing this up because I value you as part of the team and want to address this directly rather than letting it continue.”

This approach:

- Signals immediately that this is a serious conversation

- Frames your intent as supportive, not punitive

- Demonstrates respect for their time by being direct

- Sets expectations that this might be uncomfortable, which paradoxically often reduces discomfort

State the Issue Clearly and Factually

After your opening, state the issue in clear, behavioral terms: “Over the past six weeks, you’ve missed four project deadlines, including the client deliverable last Tuesday that was due at noon and arrived at 4pm. This pattern is impacting the team and our client relationships, and we need to address it.”

Notice what this does:

- Uses specific facts (six weeks, four deadlines, specific date and times)

- Describes observable behavior, not character traits

- Explains the impact clearly

- Uses “we need to address it” rather than “you need to fix it,” which frames it as collaborative

The Heart of the Conversation: Dialogue, Not Monologue

This is where inexperienced leaders often stumble. They deliver their prepared message and then either lecture at length or immediately jump to solutions, skipping the most critical phase: listening.

Create Space for Their Perspective

After stating the issue, pause. Then genuinely invite their input: “Help me understand what’s happening from your perspective” or “What’s your take on this situation?”

Then, critically, be quiet and listen. Don’t interrupt, don’t prepare your rebuttal while they’re speaking, and don’t dismiss what they share. Listen to understand, not to respond.

You might discover:

- Systemic issues you weren’t aware of that need addressing

- Personal circumstances affecting performance that require accommodation

- Misunderstandings about expectations or priorities

- Valid criticisms of your own leadership or organizational dysfunction

- Perspectives that completely reframe your understanding of the situation

Even if their explanation doesn’t change the fact that the issue needs addressing, truly listening demonstrates respect and often provides valuable information for crafting solutions.

Acknowledge Without Excusing

As they share their perspective, acknowledge their experience even if it doesn’t excuse the performance issue: “I hear that you’ve been dealing with some challenging personal circumstances. I appreciate you sharing that with me, and I want to be supportive. At the same time, we still need to ensure deadlines are met. Let’s talk about how we can do both.”

This “yes, and” approach validates their experience while maintaining accountability. It’s not “your struggles don’t matter,” nor is it “your struggles excuse everything.” It’s “your struggles matter, and we still need to address this issue.”

Ask Questions That Show Investment

Questions demonstrate that you care about understanding, not just enforcing:

- “What obstacles are you facing that I might not be aware of?”

- “What would make it easier for you to succeed in this area?”

- “How can I support you better?”

- “What resources or changes would help address this?”

These questions serve multiple purposes. They gather information, demonstrate partnership, shift from a punitive frame to a problem-solving frame, and often surface solutions neither of you had considered.

Share Impact, Not Just Rules

People are more motivated by understanding real-world consequences than by abstract rule-enforcement. Instead of “It’s company policy to arrive on time,” explain the actual impact: “When you arrive late to team meetings, we either have to repeat information or make decisions without your input, and several team members have mentioned feeling like their time isn’t valued when we have to wait or restart.”

Impact framing helps people understand the “why” behind expectations and connects their behavior to outcomes that matter.

Collaborative Problem-Solving: Moving Forward Together

Once you’ve established shared understanding of the issue, transition to solutions. This phase is what transforms a difficult conversation from demoralizing to empowering.

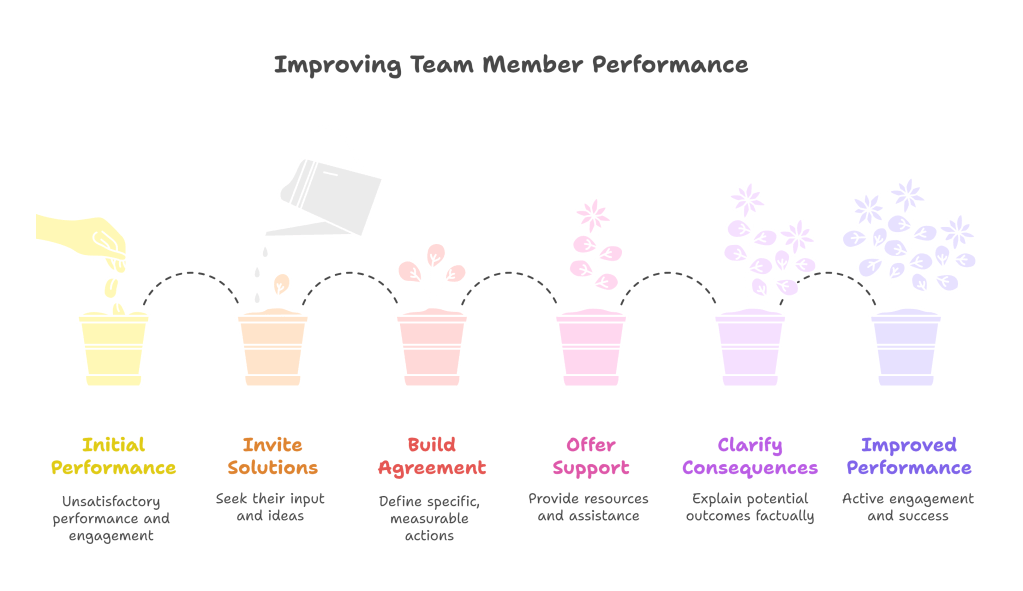

Invite Their Solutions First

Before imposing your solutions, ask: “Given what we’ve discussed, what do you think would help address this?” or “What changes can you commit to?”

This approach accomplishes several things:

- It gives them ownership over the solution, which dramatically increases commitment

- It respects their intelligence and agency

- It often surfaces better solutions than you would have imposed

- It moves them from a defensive posture to an active, engaged one

Build Agreement on Specific Actions

Vague commitments like “I’ll do better” or “I’ll work on it” set everyone up for failure. Instead, work together to define specific, measurable actions with timelines:

“So we’re agreeing that for the next month, you’ll send me a midweek progress update every Wednesday by noon, and if you see any risk to a deadline, you’ll flag it at least 48 hours in advance so we can problem-solve together. Does that seem reasonable?”

Specificity creates clarity and makes follow-up straightforward rather than awkward.

Offer Support and Resources

This is crucial for ensuring the team member leaves feeling supported rather than abandoned: “Here’s what I’ll do to support you: I’ll make sure you’re not getting competing priorities from other departments, and I’ll check in with you every Friday for the next month to see how things are going and address any obstacles early.”

By committing to specific support, you demonstrate partnership and shared responsibility for improvement.

Clarify Consequences Appropriately

If this conversation is part of a pattern or is serious enough, you may need to clarify consequences: “If we don’t see improvement over the next 30 days, we’ll need to move to a formal performance improvement plan.”

However, even when discussing consequences, frame them factually rather than as threats: “I want to be transparent with you about the process so there are no surprises. My goal is to support your success, and I’m confident we can address this together.”

The Closing: Ending on the Right Note

How you end a difficult conversation dramatically affects what the team member takes away from it. Many leaders, relieved to have gotten through the hard part, rush the closing. This is a mistake.

Reaffirm Your Confidence and Support

Before concluding, explicitly state your belief in them: “I want to emphasize that I’m having this conversation because I value you and believe in your ability to address this. You bring a lot of strengths to this team, and I want to see you succeed.”

This isn’t empty flattery; it’s reminding them that this conversation is about a specific issue, not a judgment of their worth or capability.

Invite Questions and Concerns

“What questions do you have?” or “Is there anything we haven’t discussed that you think is important?” gives them a chance to raise lingering concerns and prevents them from leaving with unspoken resentments or confusion.

Summarize Agreements Clearly

Recap the key takeaways: “Just to make sure we’re aligned, you’re going to [specific actions], and I’m going to [specific support]. We’ll check in again on [specific date] to assess progress. Does that match your understanding?”

This ensures you both leave with the same understanding and prevents future “but I thought you meant…” misunderstandings.

Express Appreciation for the Dialogue

Thank them for engaging in what you know was a difficult conversation: “I appreciate you taking the time for this conversation and approaching it constructively. I know these discussions aren’t easy.”

This acknowledges the emotional labor involved and reinforces that you see them as a partner in the process.

After the Conversation: Critical Follow-Through

What happens after the conversation often matters more than the conversation itself. This is where you either build credibility or destroy it.

Document Appropriately

Write a brief summary of what was discussed, what was agreed upon, and what the next steps are. Depending on your organization’s policies and the seriousness of the issue, you may need to share this summary with the team member or keep it in your records. Documentation protects both parties and ensures clarity.

Deliver on Your Commitments

If you promised support, resources, or check-ins, follow through without fail. Nothing undermines trust faster than a leader who makes promises in difficult conversations but doesn’t deliver. Put reminders in your calendar, block time for the check-ins you committed to, and ensure any resources you promised actually materialize.

Watch for Changes and Acknowledge Them

When you see improvement, acknowledge it immediately and specifically: “I noticed you sent the progress update right on time Wednesday and flagged the potential issue early. That’s exactly what we discussed, and it makes a huge difference. Thank you.”

Recognition of positive change reinforces the behavior and shows you weren’t just criticizing but genuinely care about their success.

Be Prepared to Address Continued Issues

If the problem persists despite the conversation, address it quickly rather than letting it slide. Failing to follow up after a difficult conversation sends the message that you didn’t really mean what you said, which undermines your credibility with both that team member and others who become aware of the situation.

However, when you do need to have a follow-up conversation, you can reference the previous discussion: “We talked about deadlines a month ago and agreed on some specific steps. I’ve noticed the pattern continuing, so we need to revisit this.”

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

The Sandwich Approach

Many leaders try to “sandwich” negative feedback between positive comments. Most people see through this technique, it dilutes your message, and it creates confusion about whether there’s actually a problem. Be direct rather than using this dated approach.

Over-Apologizing

Starting with “I’m so sorry, but…” or repeatedly apologizing throughout weakens your message. You can be empathetic without apologizing for addressing legitimate issues. Your role requires you to have these conversations.

Comparing to Others

“Everyone else manages to meet deadlines” or “Other team members don’t have this problem” creates resentment and feels like shaming. Focus on the individual’s situation and standards, not comparisons.

Bringing Up Everything

Don’t use one difficult conversation to dump every issue you’ve been harboring. Focus on the specific issue at hand. If there are patterns, name the pattern, but don’t create a litany of complaints.

Talking More Than Listening

If you’re doing more than 50% of the talking in a difficult conversation, you’re probably doing it wrong. These conversations should be dialogues, not lectures.

Avoiding Emotional Reactions

If someone gets emotional—frustrated, upset, or even angry—don’t shut it down or rush to fix it. A simple “I can see this is frustrating” or “Take the time you need” shows emotional intelligence. Sometimes people need a moment to process before they can engage productively.

Making It Personal

Keep the focus on behaviors, outcomes, and impacts, not personality traits or character judgments. “You missed the deadline” is factual. “You’re irresponsible” is a character attack that will trigger defensiveness.

Building Your Difficult Conversation Muscle

Like any leadership skill, conducting difficult conversations well requires practice. You’ll make mistakes, especially early on. That’s normal and expected. What matters is that you reflect on what worked and what didn’t, and continuously improve.

After each difficult conversation, ask yourself:

- Did the team member understand the issue clearly?

- Did I listen as much as I talked?

- Did we arrive at specific, actionable next steps?

- Did the person leave feeling respected, even if uncomfortable?

- What would I do differently next time?

Over time, you’ll develop your own style and approach that feels authentic to you. The principles outlined here aren’t a rigid script but a framework you can adapt to your personality and your team’s culture.

The Long-Term Impact: Trust Through Honesty

Here’s what many new leaders don’t initially understand: team members who receive difficult feedback skillfully delivered often end up respecting their leader more, not less. When you demonstrate that you’ll address issues directly rather than avoiding them or talking about people behind their backs, you build a reputation for integrity and trustworthiness.

Teams that work for leaders who handle difficult conversations well report higher psychological safety because they know where they stand. There’s no guessing, no politicking, no gossiping. Issues get addressed professionally and directly.

Conversely, leaders who avoid difficult conversations thinking they’re preserving relationships actually create anxiety and resentment. Team members wonder if problems are being ignored, whether poor performance is acceptable, and if feedback is genuine or just being nice.

Conclusion

The ability to deliver difficult messages while maintaining relationships and motivation is perhaps the most important skill for team leaders to develop. It separates adequate managers from truly effective leaders.

The framework is straightforward but not easy: prepare thoroughly, open with direct respect, listen genuinely, problem-solve collaboratively, close with affirmation and clarity, and follow through consistently. Throughout, maintain the dual commitment to both high standards and genuine care for people.

When you master this balance, difficult conversations transform from something you dread into opportunities for growth, clarity, and strengthened relationships. Your team members may not always like what they hear, but they’ll leave feeling respected, clear about expectations, supported in their development, and confident that you care about their success.

That’s not just good management—that’s genuine leadership. And it’s entirely within your reach.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.