Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with information, offering unprecedented capabilities in understanding, generating, and summarizing text. However, a common challenge arises when LLMs need to provide accurate, up-to-date, or domain-specific information that wasn’t part of their original training data. This is where Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) comes into play.

RAG is a powerful paradigm that combines the generative power of LLMs with the ability to retrieve relevant information from external knowledge bases. Instead of solely relying on their internal parametric knowledge, RAG systems first retrieve pertinent documents or data snippets based on a user’s query and then use this retrieved context to inform the LLM’s generation process. This approach significantly reduces hallucinations, improves factual accuracy, and allows LLMs to stay current with rapidly changing information without constant retraining.

While basic RAG involves a straightforward retrieve-then-generate process, the complexity and demands of real-world applications necessitate more sophisticated techniques. This article delves into advanced RAG methodologies that push the boundaries of what’s possible, enabling LLMs to handle intricate queries, leverage diverse data sources, and deliver highly precise and contextually rich responses. We will explore nine key advanced RAG techniques, dissecting their mechanisms, advantages, and ideal use cases.

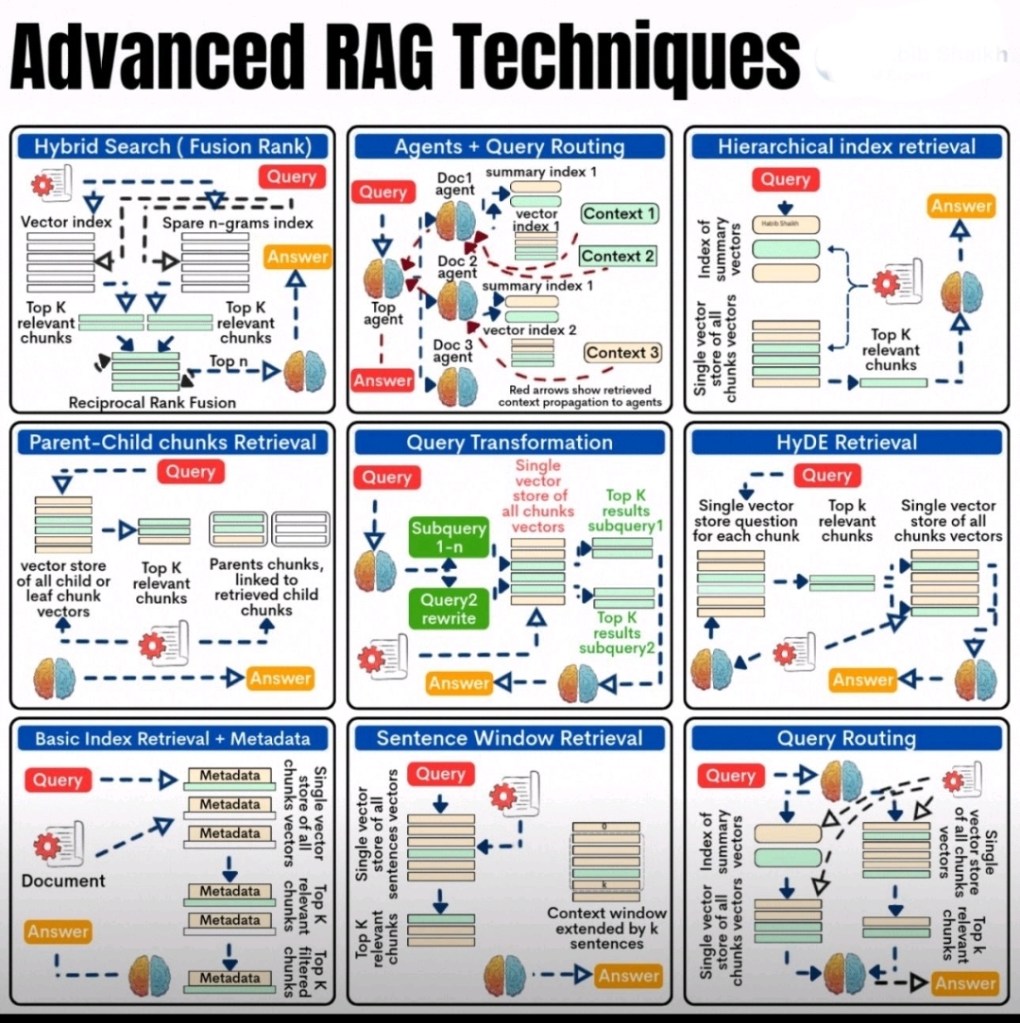

1. Hybrid Search (Fusion Rank)

Purpose:

Traditional information retrieval often relies on either keyword matching (lexical search) or semantic similarity (vector search). Lexical search excels at finding exact matches and specific terms but struggles with synonyms or conceptual relationships. Vector search, based on embeddings, captures semantic meaning but can sometimes miss highly relevant documents if their embeddings are not perfectly aligned or if specific keywords are crucial. Hybrid Search, particularly with Fusion Rank, aims to combine the strengths of both approaches to achieve superior retrieval performance. It addresses the limitations of relying solely on one retrieval method by leveraging the complementary nature of lexical and semantic signals.

Mechanism/Workflow:

The core idea of Hybrid Search is to perform parallel searches using different retrieval mechanisms and then intelligently combine their results.

- Parallel Retrieval:

- Vector Index Search: The user’s query is embedded into a vector space. This query vector is then used to search a “Vector Index” (often a dense vector index) containing embeddings of document chunks. The search identifies document chunks that are semantically similar to the query. This typically yields a “Top K relevant chunks” based on cosine similarity or other distance metrics.

- Sparse N-grams Index Search: Simultaneously, the query is used to perform a lexical search against a “Sparse N-grams Index” (e.g., using BM25, TF-IDF, or other sparse retrieval models). This index stores information about the frequency and distribution of n-grams (sequences of words) within the documents. This search identifies document chunks that contain relevant keywords or phrases, also yielding a “Top K relevant chunks.”

- Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF):Once both retrieval methods have produced their respective lists of top-K relevant chunks, a crucial step is to combine these lists effectively. Simple union or intersection might not be optimal. Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) is a popular and effective ranking algorithm used for this purpose.For each document chunk d that appears in any of the retrieved lists, RRF calculates a score using the formula:Score(d)=r∈retrievers∑rankr(d)+k1Where:

- rankr(d) is the rank of document d in the results from retriever r. If a document is not returned by a specific retriever, it’s typically assigned a very low (or infinite) rank.

- k is a constant, often set to a small value (e.g., 60), which smooths the contribution of lower-ranked results. It ensures that even documents ranked lower by one retriever can still contribute meaningfully if they are highly ranked by another.

Key Components:

- Vector Index: Stores dense vector embeddings of document chunks.

- Sparse N-grams Index: Stores lexical information, enabling keyword-based search.

- Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) Algorithm: A ranking algorithm to combine results from multiple retrievers.

Advantages:

- Improved Recall and Precision: By combining lexical and semantic signals, Hybrid Search is more robust to query variations, synonyms, and specific keyword requirements. It can retrieve documents that might be missed by a pure semantic search (due to lexical mismatch) or a pure lexical search (due to semantic similarity but no exact keyword match).

- Robustness: Less sensitive to the quality of embeddings or the exact phrasing of the query.

- Enhanced User Experience: Leads to more comprehensive and accurate answers by providing richer context to the LLM.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Complexity: Requires maintaining and querying multiple indices.

- Higher Computational Cost: Running parallel searches and then fusing results adds overhead compared to a single retrieval method.

- Tuning RRF Parameter: The constant k in RRF might need tuning for optimal performance on specific datasets.

Use Cases:

- General-purpose Q&A systems: Where queries can be diverse, ranging from highly specific keyword searches to abstract conceptual questions.

- Enterprise search: Combining structured metadata search with full-text search.

- E-commerce product search: Where both exact product names/SKUs and descriptive features are important.

- Legal or medical document retrieval: Ensuring both precise terminology and conceptual relevance are captured.

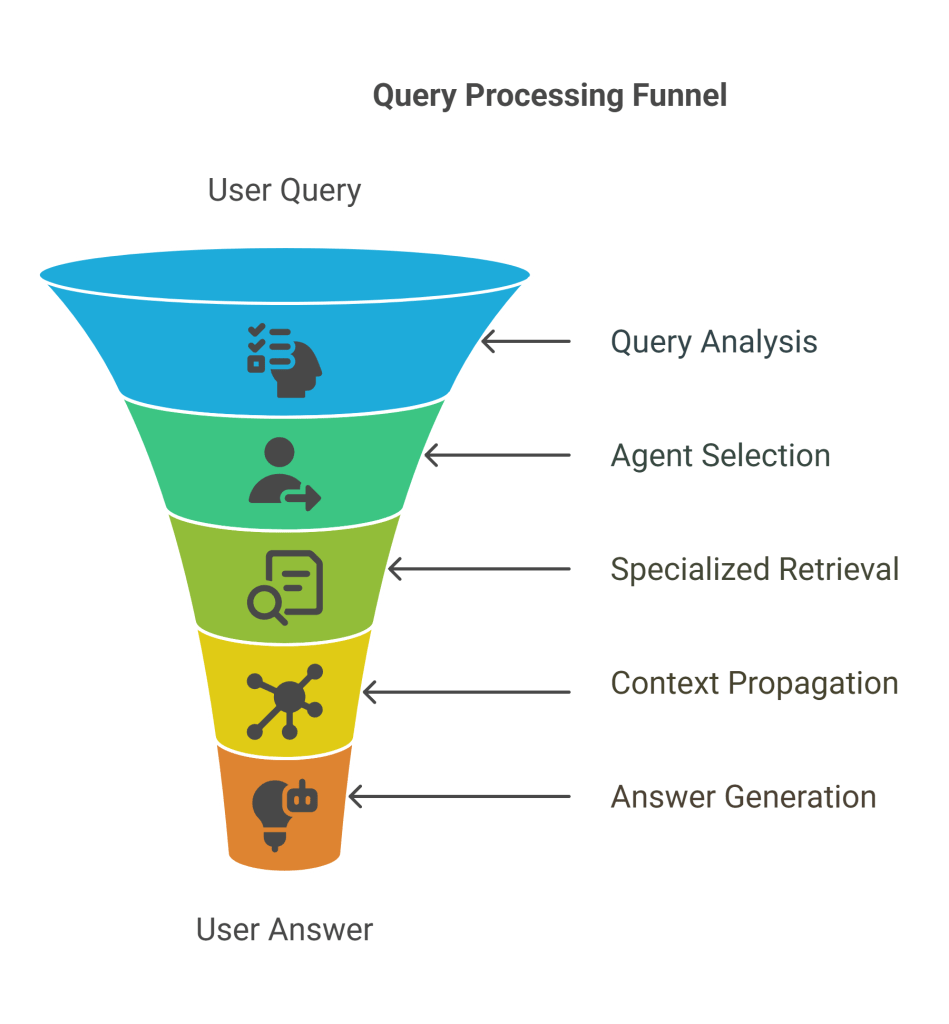

2. Agents + Query Routing

Purpose:

As RAG systems grow in complexity and the underlying knowledge base becomes more diverse, a single, monolithic retrieval approach can become inefficient or insufficient. Different types of queries might require different retrieval strategies or access to specialized subsets of the knowledge base. Agents + Query Routing addresses this by introducing an intelligent routing mechanism that directs a user’s query to the most appropriate “agent” or retrieval pipeline, each specialized for a particular domain, data type, or query intent. This allows for more targeted and efficient retrieval, leading to higher quality and more relevant responses.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique introduces an orchestration layer that acts as a traffic controller for incoming queries.

- Initial Query Reception: A user submits a “Query.”

- Query Analysis and Routing: An initial “agent” (often a small LLM or a classification model) analyzes the incoming query to determine its intent, domain, or the type of information required. This analysis might involve:

- Summary Index 1 (or multiple summary indices): The query might be compared against a high-level summary index of available knowledge domains or agent capabilities. For example, a summary index might indicate that “Agent 1” handles financial queries, “Agent 2” handles technical support, and “Agent 3” handles product information.

- Classification: The initial agent classifies the query into predefined categories.

- Keyword Matching: Simple keyword rules can also guide routing.

- Agent Selection: Based on the analysis, the query is routed to the most suitable specialized “Doc Agent” (e.g., Doc 1 agent, Doc 2 agent, Doc 3 agent in the diagram). Each Doc Agent is essentially a mini-RAG system or a specialized retrieval pipeline.

- Specialized Retrieval by Agents:

- Each Doc Agent is associated with its own specific knowledge base or retrieval index (e.g., “vector index 1,” “vector index 2,” etc., or a “summary index” for further sub-routing).

- The selected Doc Agent performs its specialized retrieval operation. For instance, “Doc 1 agent” might retrieve context from “vector index 1” and “summary index 1,” generating “Context 1.” Similarly, “Doc 2 agent” generates “Context 2,” and “Doc 3 agent” generates “Context 3.”

- Context Propagation and Answer Generation: The “Red arrows show retrieved context propagation to agents.” This indicates that the context retrieved by the specialized Doc Agents is then passed back to a central “Top agent” or a final LLM for synthesis. This central agent integrates the retrieved contexts and generates the final “Answer” to the user’s query. In some advanced setups, agents might even interact iteratively, refining their search based on partial results from other agents.

Key Components:

- Query Router/Initial Agent: Determines the appropriate specialized agent for a given query.

- Specialized Doc Agents: Each agent is responsible for a specific domain or retrieval task, potentially having its own dedicated indices (e.g., vector index, summary index).

- Summary Indices: High-level indices that describe the content or capabilities of different specialized knowledge bases or agents, used by the router.

- Context Propagation Mechanism: How retrieved contexts from specialized agents are combined or passed to a final generation step.

Advantages:

- Domain Specialization: Allows for highly accurate and relevant responses by directing queries to experts within the knowledge base.

- Scalability: Facilitates managing very large and diverse knowledge bases by segmenting them. New domains can be added by simply creating new agents without affecting existing ones.

- Efficiency: Prevents unnecessary searches across the entire knowledge base, reducing retrieval time and computational resources.

- Improved Accuracy: By focusing retrieval on relevant sub-sections, the quality of retrieved context improves, leading to better LLM outputs.

- Complex Query Handling: Can decompose complex, multi-faceted queries into sub-queries routed to different agents.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased System Complexity: Designing, training, and managing multiple agents and routing logic can be challenging.

- Routing Accuracy: The performance heavily depends on the accuracy of the initial query routing. Misrouting can lead to poor answers.

- Agent Coordination: For very complex queries, coordinating responses from multiple agents can be difficult.

Use Cases:

- Large enterprise knowledge bases: Where different departments or products have their own documentation.

- Customer support chatbots: Routing queries to specific product or service support agents.

- Multi-domain information retrieval: Systems that need to answer questions across various topics like finance, technology, and healthcare.

- Research assistants: Directing queries to specific scientific literature databases.

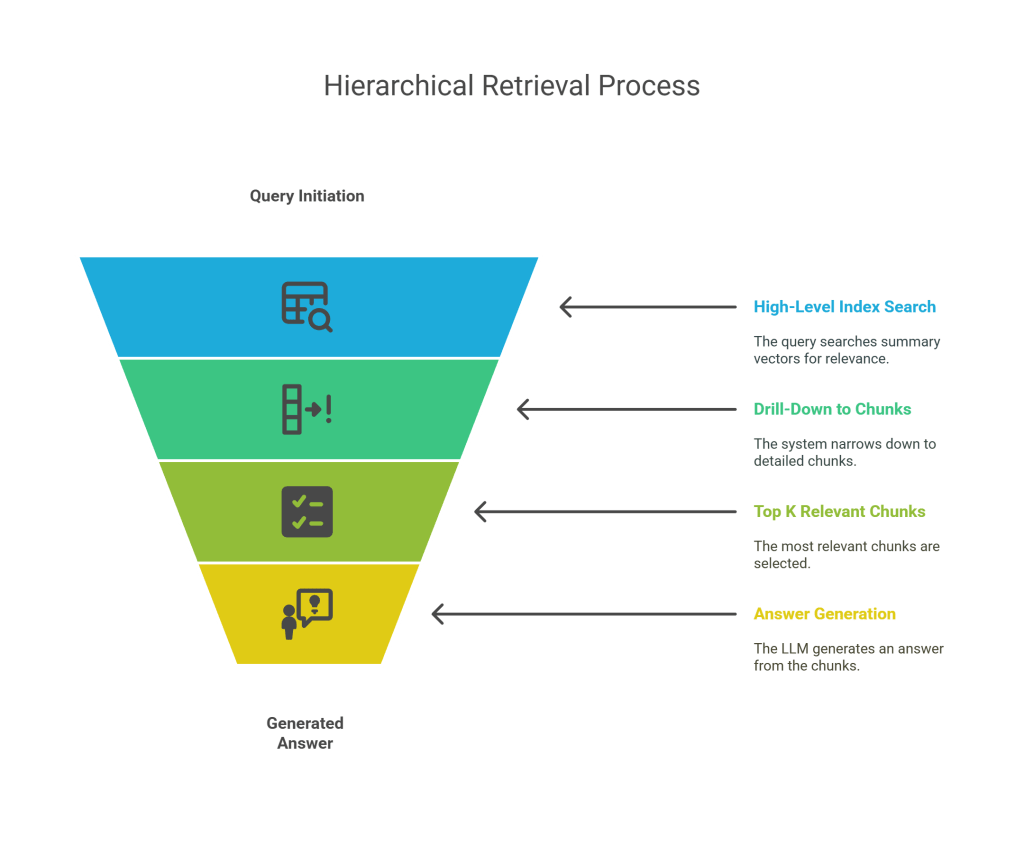

3. Hierarchical Index Retrieval

Purpose:

For extremely large knowledge bases, a flat index structure (where all document chunks are in a single vector store) can become inefficient for retrieval. Searching through millions or billions of chunks for every query is computationally expensive and can lead to slower response times. Hierarchical Index Retrieval addresses this by organizing the knowledge base into a multi-level structure, enabling more efficient and targeted retrieval by progressively narrowing down the search space. It’s akin to navigating a table of contents before diving into specific chapters.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique leverages a multi-stage retrieval process, moving from a high-level overview to detailed content.

- Query Initiation: A “Query” is received.

- High-Level Index Search (Summary Vectors): The query is first used to search an “Index of summary vectors.” These summary vectors represent higher-level concepts, topics, or summaries of larger document sections (e.g., chapters, entire documents, or clusters of related chunks). This initial search identifies the most relevant high-level summaries.

- Drill-Down to Detailed Chunks: Once the relevant summary vectors are identified, the system then “drills down” into the specific, detailed “Single vector store of all chunks vectors” that are associated with those relevant summaries. This means instead of searching the entire chunk vector store, the search is confined to a much smaller subset of chunks that are known to be relevant to the high-level summary.

- Top K Relevant Chunks: From this narrowed down set of detailed chunks, the “Top K relevant chunks” are retrieved. These are the most granular pieces of information that are directly relevant to the query based on the initial high-level filtering.

- Answer Generation: The retrieved chunks are then passed to the LLM to generate the “Answer.”

Key Components:

- Index of Summary Vectors: A high-level index containing embeddings of summaries or abstract representations of larger content blocks.

- Single Vector Store of All Chunks Vectors: The granular index containing embeddings of individual document chunks.

- Mapping/Linkage: A mechanism that links summary vectors to the specific granular chunks they summarize.

Advantages:

- Efficiency for Large Datasets: Significantly reduces the search space for each query, leading to faster retrieval times for very large knowledge bases.

- Improved Relevance: By first identifying broad relevant topics, the subsequent granular search is more likely to yield highly relevant chunks, as irrelevant sections are pruned early.

- Scalability: Easier to manage and scale knowledge bases as they grow, as updates can be localized to specific hierarchical levels.

- Contextual Understanding: The hierarchical structure can help the LLM understand the broader context from which the specific chunks were retrieved.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Indexing Complexity: Creating and maintaining hierarchical indices (generating summaries, linking them to chunks) adds complexity to the indexing pipeline.

- Potential for Information Loss: If the high-level summaries are not sufficiently representative, relevant granular chunks might be missed in the initial filtering step.

- Query Ambiguity: Highly ambiguous queries might struggle to find a clear path through the hierarchy.

Use Cases:

- Very large document repositories: Such as legal databases, scientific literature archives, or extensive corporate knowledge bases.

- Long-form content: Books, manuals, or research papers where information is structured hierarchically.

- Conversational AI for broad domains: Where initial query can be broad, requiring a drill-down to specific details.

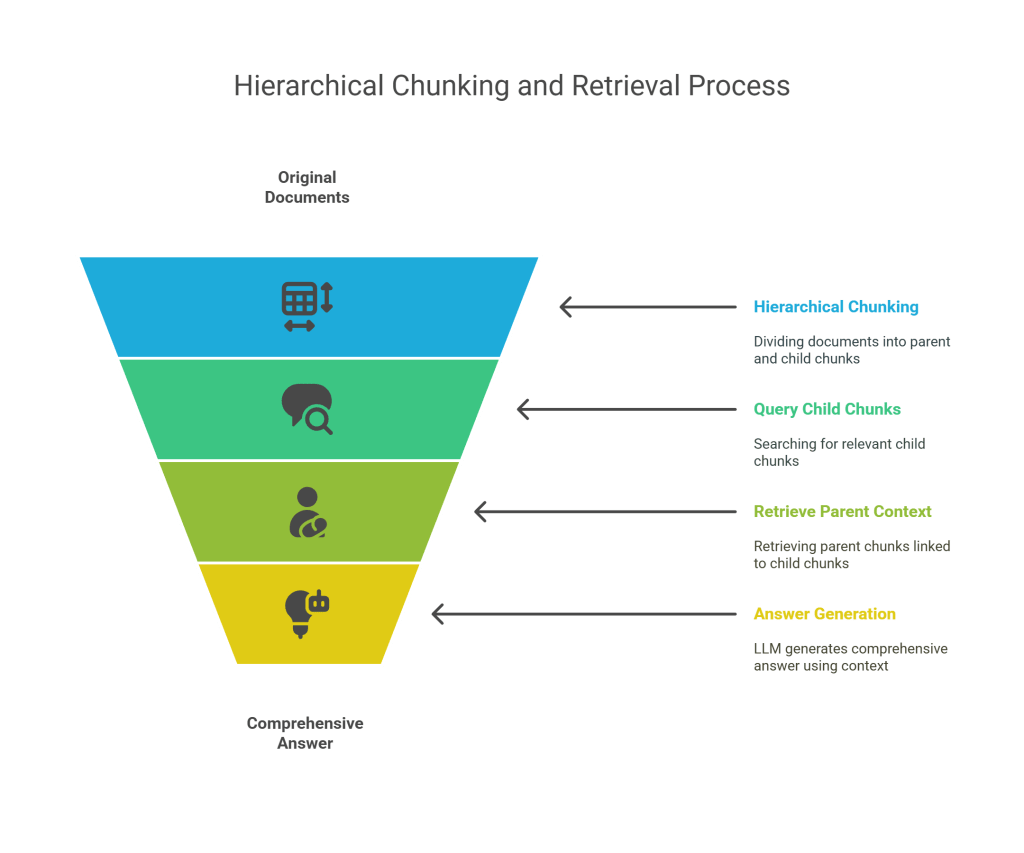

4. Parent-Child Chunks Retrieval

Purpose:

Standard RAG often involves splitting documents into fixed-size chunks. While effective, this can sometimes lead to a dilemma:

- Small chunks: Provide precise context but might lack broader surrounding information necessary for the LLM to fully understand the retrieved snippet.

- Large chunks: Offer more context but can introduce irrelevant information, dilute the signal, and increase token consumption for the LLM.Parent-Child Chunks Retrieval aims to solve this by optimizing the chunking strategy. It retrieves small, precise “child” chunks for high relevance and then expands the context by including their larger “parent” chunks, providing a richer contextual understanding to the LLM without sacrificing retrieval precision.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique involves a two-tiered chunking and retrieval process:

- Hierarchical Chunking:

- Parent Chunks: The original documents are first divided into larger, more contextually rich “parent chunks.” These might be paragraphs, sections, or even entire pages.

- Child Chunks: Each parent chunk is then further subdivided into smaller, more granular “child chunks.” These child chunks are typically sentences or small groups of sentences, designed for precise semantic matching with queries.

- Linkage: A crucial aspect is that each child chunk retains a link or reference to its corresponding parent chunk.

- Querying the Child Chunks:

- A “Query” is received.

- The query is used to search a “vector store of all child or leaf chunk vectors.” This means the initial retrieval focuses on finding the most semantically similar small child chunks.

- This step yields “Top K relevant chunks” which are the precise child chunks that match the query.

- Retrieving Parent Context:

- Once the top-K child chunks are identified, the system uses their inherent “linked to retrieved child chunks” property to retrieve their corresponding “Parents chunks.”

- Instead of sending just the small child chunks to the LLM, the larger parent chunks that contain these relevant children are retrieved. This provides the broader context.

- Answer Generation: The LLM receives the larger parent chunks as context, enabling it to generate a more comprehensive and accurate “Answer” because it has access to both the precise relevant snippet and its surrounding explanatory information.

Key Components:

- Parent Chunks: Larger, context-rich segments of documents.

- Child Chunks: Smaller, granular segments derived from parent chunks.

- Vector Store of Child Chunks: Used for initial, precise retrieval.

- Linkage Mechanism: To associate child chunks with their parent chunks.

Advantages:

- Optimized Context: Provides the LLM with a balance of precision (from child chunks) and broader context (from parent chunks), leading to more coherent and factually grounded answers.

- Reduced Noise: The initial retrieval on small child chunks minimizes the amount of irrelevant information retrieved, while the parent chunks ensure sufficient context.

- Improved LLM Performance: LLMs often perform better when provided with relevant context that is neither too narrow nor too broad.

- Handles Granularity: Addresses scenarios where a query might be very specific, but the answer requires understanding the surrounding text.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Indexing Complexity: Requires a more sophisticated chunking and indexing pipeline to create and manage parent-child relationships.

- Storage Overhead: Storing both parent and child chunk embeddings can increase storage requirements.

- Design of Parent/Child Sizes: Determining optimal sizes for parent and child chunks can be non-trivial and may require experimentation.

Use Cases:

- Technical documentation: Where specific code snippets (child) need broader explanation (parent).

- Legal documents: Retrieving specific clauses (child) while providing the full section or article (parent) for context.

- Medical research papers: Finding a specific finding (child) and then providing the methodology or discussion section (parent).

- Any domain where precise answers benefit from surrounding context.

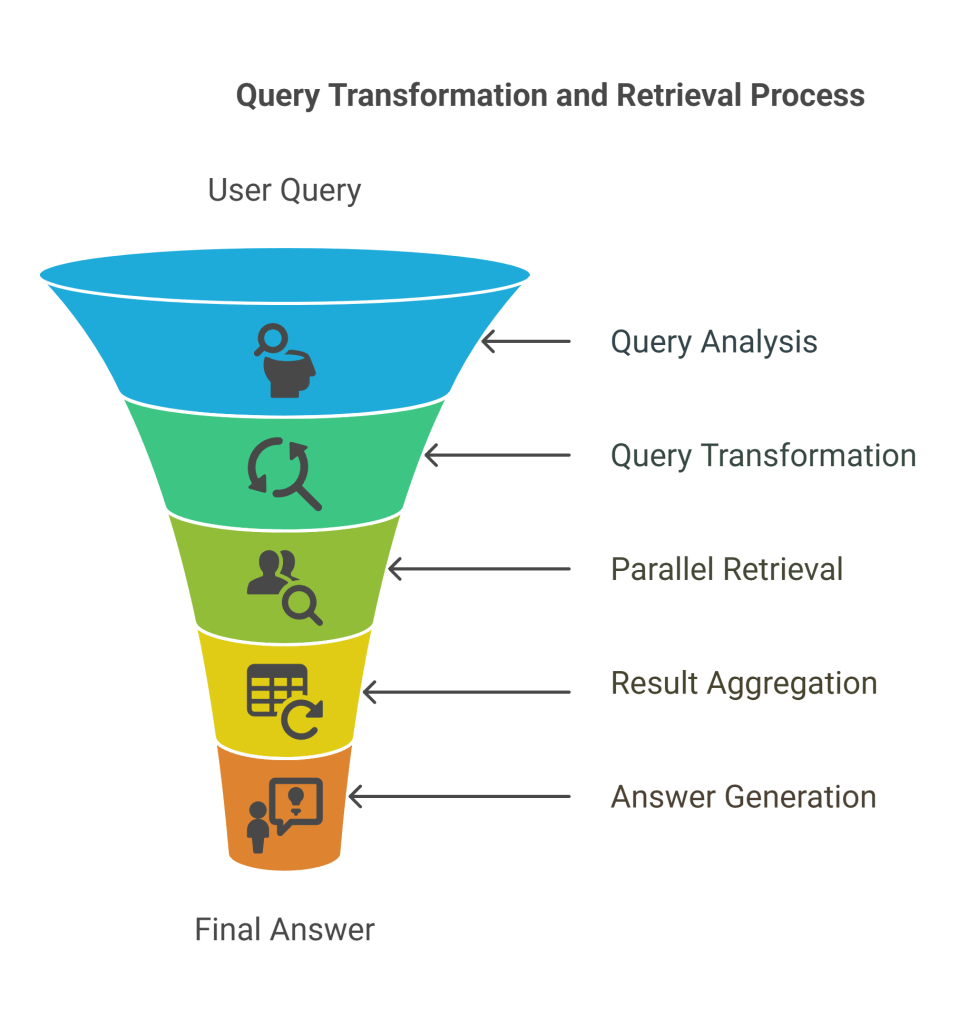

5. Query Transformation

Purpose:

User queries can often be ambiguous, underspecified, contain jargon, or be phrased in a way that doesn’t directly align with the terminology or structure of the knowledge base. A direct retrieval with such queries might yield suboptimal results. Query Transformation addresses this by intelligently rephrasing, expanding, or decomposing the original query into one or more optimized queries that are more likely to retrieve relevant information from the vector store. This acts as a pre-processing step to improve retrieval effectiveness.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique leverages an LLM or a set of rules to modify the original query before retrieval.

- Initial Query Reception: A “Query” is received from the user.

- Query Analysis and Transformation: An LLM (or a rule-based system) analyzes the original query. Based on this analysis, it performs one or more transformations:

- Subquery Generation: For complex or multi-faceted queries, the LLM can decompose the original query into multiple “Subquery 1-n.” For example, “What are the health benefits of blueberries and how do they compare to strawberries?” could be transformed into “health benefits of blueberries” and “comparison of blueberries and strawberries.”

- Query Rewriting/Paraphrasing: The LLM can “Query2 rewrite” the original query into a more effective form. This might involve:

- Adding keywords.

- Removing stop words or irrelevant phrases.

- Rephrasing to match common terminology in the knowledge base.

- Expanding abbreviations.

- Generating hypothetical questions that the documents might answer.

- Parallel or Sequential Retrieval:

- If multiple subqueries are generated, each “Subquery” is then used to search the “Single vector store of all chunks vectors” independently. This yields “Top K results subquery 1,” “Top K results subquery 2,” and so on.

- If the query was rewritten, the rewritten query is used for a single retrieval.

- Result Aggregation: The results from all subqueries are then aggregated. This might involve simple concatenation, de-duplication, or a re-ranking mechanism (like RRF, though not explicitly shown in this diagram for aggregation).

- Answer Generation: The combined retrieved chunks are then passed to the LLM to generate the final “Answer.”

Key Components:

- Query Transformation Model: An LLM or a rule-based system capable of analyzing and modifying queries.

- Single Vector Store of All Chunks Vectors: The primary knowledge base for retrieval.

- Result Aggregation Logic: To combine results from multiple subqueries.

Advantages:

- Improved Retrieval Accuracy: By optimizing the query, the system is more likely to retrieve truly relevant documents, even if the original query was imperfect.

- Handles Ambiguity: Can clarify ambiguous queries by generating multiple interpretations or more specific sub-queries.

- Adapts to Knowledge Base: Can rephrase queries to better match the language and concepts present in the indexed documents.

- Enhanced User Experience: Users don’t need to formulate perfect queries; the system intelligently adapts.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Latency: The transformation step adds an extra processing layer before retrieval.

- Complexity of Transformation Model: Designing and fine-tuning the query transformation model (especially if it’s an LLM) can be challenging.

- Potential for Misinterpretation: The transformation model might sometimes misinterpret the user’s intent and generate ineffective queries.

- Cost of LLM Calls: If an LLM is used for transformation, it adds to the operational cost.

Use Cases:

- Conversational AI systems: Where user queries are often informal, incomplete, or multi-turn.

- Customer service chatbots: To rephrase user problems into searchable terms.

- Search engines: To expand or refine user searches for better results.

- Any RAG system where query quality from users is variable.

6. HyDE Retrieval (Hypothetical Document Embedding)

Purpose:

Semantic search relies on the similarity between the query embedding and document embeddings. However, a significant challenge is the “lexical gap” or “modality gap” – the query might be short and phrased differently from how the answer is presented in the documents, even if they are semantically related. HyDE (Hypothetical Document Embedding) Retrieval addresses this by generating a “hypothetical document” or a “hypothetical answer” based on the user’s query. This hypothetical document, being longer and more descriptive, often provides a richer semantic context that aligns better with actual document embeddings, leading to more accurate retrieval.

Mechanism/Workflow:

HyDE introduces an intermediate generation step to bridge the gap between query and document representation.

- Query Reception: A “Query” is received.

- Hypothetical Document Generation: An LLM is prompted with the user’s query to generate a “Single vector store question for each chunk” or, more generally, a “hypothetical document” (or answer) that would contain the answer to the query. This hypothetical document is not intended to be factually accurate but rather semantically rich and representative of what a relevant document might look like.

- Example: If the query is “What are the benefits of meditation?”, the LLM might generate a hypothetical document like: “Meditation offers numerous benefits for mental and physical well-being. Regular practice can reduce stress, improve focus, enhance emotional regulation, and promote feelings of calm and inner peace. It has also been linked to better sleep quality and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression.”

- Embedding the Hypothetical Document: The generated hypothetical document is then embedded into a vector. This vector is typically more robust and representative of the query’s semantic intent than the original short query’s embedding.

- Retrieval with Hypothetical Embedding: This hypothetical document’s embedding is then used to search the “Single vector store of all chunks vectors” (which contains embeddings of actual document chunks). Because the hypothetical document is richer in semantic content, its embedding is often a better match for relevant actual document chunks.

- Top K Relevant Chunks: This search retrieves the “Top k relevant chunks” from the actual knowledge base.

- Answer Generation: These retrieved chunks are then passed to the LLM (which might be the same or a different LLM from the one that generated the hypothetical document) to synthesize the final “Answer.” The LLM uses the actual retrieved chunks, not the hypothetical document, for its factual basis.

Key Components:

- Hypothetical Document Generator (LLM): An LLM used to create a semantically rich hypothetical document from the query.

- Embedding Model: To embed both the hypothetical document and the actual document chunks.

- Single Vector Store of All Chunks Vectors: The knowledge base.

Advantages:

- Addresses Lexical Gap: Bridges the semantic and lexical differences between short queries and longer, more detailed documents.

- Improved Semantic Matching: The hypothetical document provides a richer context for embedding, leading to more accurate semantic similarity searches.

- Robustness to Query Phrasing: Less sensitive to the exact wording of the user’s query.

- Enhanced Retrieval for Complex Queries: Can help retrieve relevant information even for abstract or underspecified queries.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Latency: Adds an extra LLM inference step before retrieval.

- Computational Cost: Involves an additional LLM call for each query.

- Hypothetical Document Quality: The effectiveness depends on the LLM’s ability to generate a good hypothetical document. A poor hypothetical document can lead to irrelevant retrieval.

- No Factual Guarantee: The hypothetical document is not factual and should not be used as context for the final answer; only its embedding is used for retrieval.

Use Cases:

- Open-domain Q&A: Where queries can be very diverse and unstructured.

- Knowledge discovery: When users are exploring a topic and their initial queries might be broad.

- Systems dealing with highly nuanced or conceptual information.

- Improving retrieval for short, keyword-poor queries.

7. Basic Index Retrieval + Metadata

Purpose:

While vector search is powerful for semantic similarity, many documents also contain valuable structured or semi-structured information in the form of metadata (e.g., author, date, document type, source, tags, categories). Basic Index Retrieval augmented with Metadata leverages this additional information to filter, refine, or enhance the retrieval process, ensuring that the retrieved chunks not only are semantically relevant but also meet specific criteria or constraints. This is particularly useful for controlling the scope of retrieval or adding factual constraints.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique integrates metadata filtering or boosting into the standard vector retrieval process.

- Document Indexing with Metadata: When a “Document” is chunked and indexed, each “chunk” is associated with its relevant “Metadata.” This metadata can include:

- Source: Which document it came from.

- Author: Who wrote it.

- Date: When it was published or last updated.

- Type: e.g., “report,” “article,” “FAQ,” “policy.”

- Tags/Keywords: Manually assigned or extracted keywords.

- Security Level: Access restrictions.

- Domain/Topic: Specific subject matter.This metadata is stored alongside the chunk’s vector embedding in the “Single vector store of all chunks vectors.”

- Query with Metadata Constraints: A “Query” is received. This query might implicitly or explicitly include metadata constraints. For example, “What are the latest policies on remote work from 2023?” Here, “latest,” “policies,” and “2023” are potential metadata filters.

- Retrieval and Filtering:

- The query is used to perform a vector search against the “Single vector store of all chunks vectors,” yielding “Top K relevant chunks.”

- Crucially, these retrieved chunks are then “Top K filtered” based on their associated “Metadata.” This filtering can happen before, during, or after the vector search, depending on the implementation.

- Pre-filtering: Only search chunks that match metadata criteria (e.g., only search “policy” documents).

- Post-filtering: Retrieve broadly, then filter the results by metadata.

- Re-ranking/Boosting: Use metadata to boost the scores of relevant chunks (e.g., prioritize newer documents).

- Answer Generation: The “Top K filtered” chunks are then passed to the LLM to generate the “Answer.”

Key Components:

- Metadata: Structured information associated with each document chunk.

- Single Vector Store of All Chunks Vectors: Stores both embeddings and associated metadata.

- Metadata Filtering/Boosting Logic: To apply constraints or preferences based on metadata during or after retrieval.

Advantages:

- Precise Control over Retrieval: Allows users to specify exact criteria (e.g., “only documents from 2024,” “only FAQs”).

- Reduced Irrelevance: Filters out semantically similar but contextually irrelevant documents based on metadata constraints.

- Enhanced Factual Accuracy: Ensures the LLM receives context that adheres to specific factual or temporal requirements.

- Improved User Experience: Users can refine their searches more effectively.

- Compliance/Security: Can enforce access controls or data governance by filtering based on user permissions or data sensitivity metadata.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Metadata Management: Requires a robust system for extracting, storing, and managing metadata.

- Consistency: Metadata must be consistent and accurate across the knowledge base.

- Query Parsing: The system needs to effectively parse metadata constraints from natural language queries.

- Complexity: Integrating metadata filtering adds complexity to the retrieval pipeline.

Use Cases:

- Enterprise search: Filtering documents by department, project, author, or date.

- Legal research: Searching for specific case types, jurisdictions, or dates.

- News aggregation: Retrieving articles from specific sources or within a certain time frame.

- Product catalogs: Filtering by brand, price range, or features.

- Any system where specific attributes beyond semantic content are important for retrieval.

8. Sentence Window Retrieval

Purpose:

When documents are chunked, a common approach is to use fixed-size chunks (e.g., 256 or 512 tokens). However, the most semantically relevant information for a query might reside in a single sentence or a very small group of sentences. Retrieving a larger chunk containing this sentence can introduce noise, while retrieving only the single sentence might strip away crucial surrounding context needed for the LLM to fully understand and synthesize the answer. Sentence Window Retrieval offers a refined approach by focusing on precise sentence-level retrieval and then dynamically expanding the context around the retrieved sentence.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique involves a two-step process: precise retrieval followed by context expansion.

- Sentence-Level Indexing:

- The original document is broken down into individual “sentences.”

- Each sentence is then embedded, and these embeddings are stored in a “Single vector store of all sentences vectors.” This allows for highly granular semantic search.

- Precise Sentence Retrieval:

- A “Query” is received.

- The query is used to search the “Single vector store of all sentences vectors.”

- This search identifies the “Top K relevant chunks” which, in this case, are individual sentences that are most semantically similar to the query.

- Context Window Expansion:

- Once the top-K relevant sentences are identified, the system then “Context window extended by k sentences.” This means for each retrieved sentence, a window of surrounding sentences (e.g.,

ksentences before andksentences after the retrieved sentence from the original document) is dynamically retrieved. - This expansion ensures that the LLM receives not just the precise answer sentence but also its immediate surrounding context, which is often vital for understanding nuances, references, or the flow of information.

- Once the top-K relevant sentences are identified, the system then “Context window extended by k sentences.” This means for each retrieved sentence, a window of surrounding sentences (e.g.,

- Answer Generation: The LLM receives these expanded context windows (the retrieved sentence plus its surrounding sentences) to generate the “Answer.”

Key Components:

- Sentence Splitter: To break documents into individual sentences.

- Single Vector Store of All Sentences Vectors: The index for precise sentence-level retrieval.

- Context Window Expansion Logic: To dynamically retrieve surrounding sentences from the original document based on the position of the retrieved sentence.

Advantages:

- High Precision: Retrieves the most semantically relevant sentences directly.

- Optimized Context: Provides just enough surrounding context without overwhelming the LLM with irrelevant information.

- Reduced Token Usage: By providing focused context, it can reduce the number of tokens sent to the LLM, potentially lowering inference costs and improving speed.

- Better LLM Performance: LLMs often perform better when the context is tightly focused on the relevant information.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Increased Indexing Granularity: Requires indexing at the sentence level, which can lead to a very large number of small chunks.

- Contextual Coherence: While expanding the window helps, there’s a risk that the “k” sentences might not always capture the entire necessary context if the relevant information spans across non-contiguous sentences.

- Computational Overhead: Dynamically retrieving and assembling context windows adds a step to the retrieval process.

Use Cases:

- Fact extraction: When the answer is likely to be contained within a single sentence or a very short phrase.

- Summarization: To identify key sentences and then provide minimal surrounding context for an LLM to summarize.

- Question answering where conciseness is valued.

- Systems dealing with highly dense or technical documents where every sentence carries significant meaning.

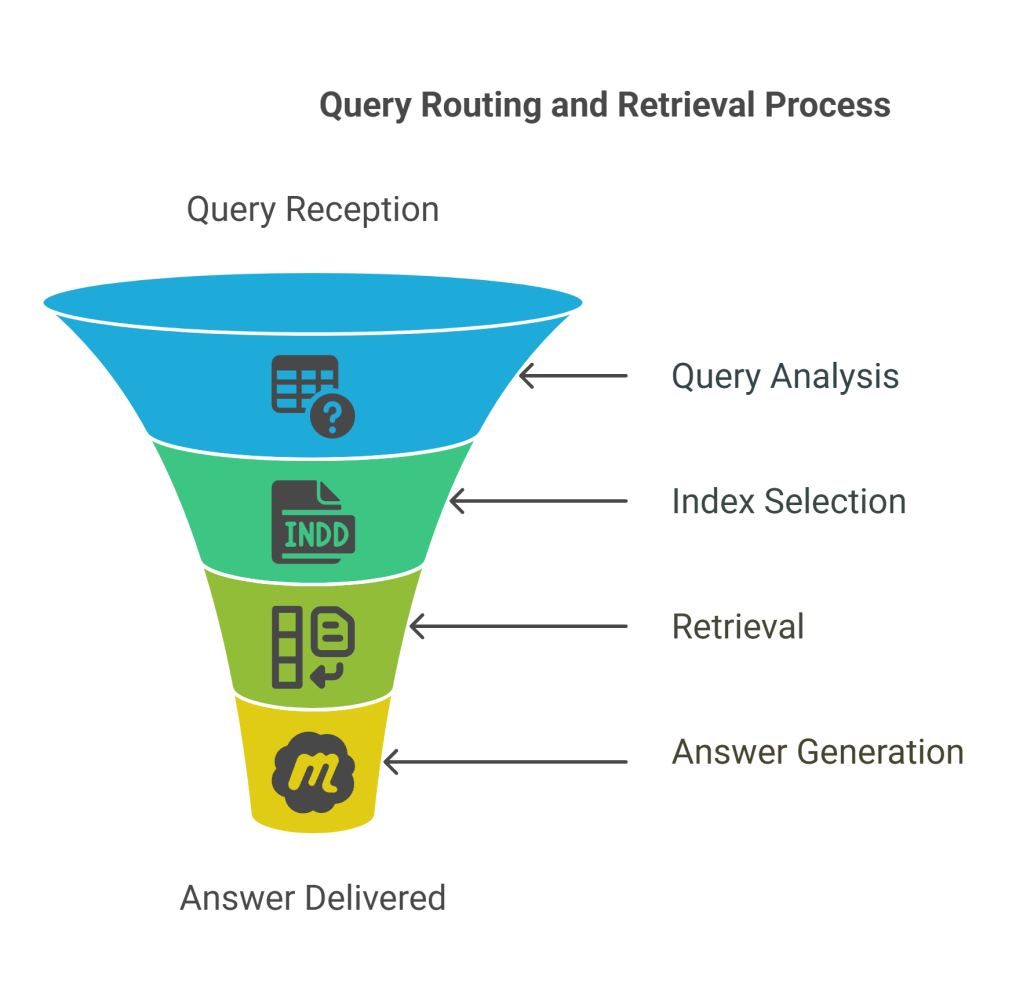

9. Query Routing (Generalized)

Purpose:

As seen earlier with “Agents + Query Routing,” the concept of directing a query to the most appropriate knowledge source or retrieval strategy is fundamental for building scalable and efficient RAG systems. This generalized “Query Routing” technique emphasizes the intelligent dispatch of a query to different underlying retrieval mechanisms or indices based on the query’s characteristics, intent, or the type of information sought. Unlike the agent-based approach which implies a more complex, potentially iterative interaction, this generalized routing might be simpler, directly choosing an index.

Mechanism/Workflow:

This technique involves an initial classification or analysis of the query to determine the best path for retrieval.

- Query Reception: A “Query” is received.

- Query Analysis and Routing Logic: An intelligent routing component analyzes the query. This analysis can be based on:

- Keywords: Specific keywords indicating a domain (e.g., “financial report” -> financial index).

- Semantic Similarity: Comparing the query’s embedding to embeddings of “Index of summary vectors” (representing different knowledge domains or types of content).

- LLM-based Classification: An LLM can classify the query into predefined categories, each mapped to a specific index.

- Heuristics/Rules: Predefined rules based on query structure or length.

- Index Selection: Based on the routing logic, the query is directed to the most appropriate “Single vector store of all chunks vectors” or an “Index of summary vectors” (if a hierarchical approach is preferred for that specific route). The diagram shows routing to either a summary index or directly to a chunk vector store.

- Route 1 (via Summary Index): The query goes to an “Index of summary vectors.” This suggests a hierarchical retrieval path, where the system first identifies relevant high-level topics or documents, then drills down to granular chunks.

- Route 2 (Direct to Chunk Vector Store): The query goes directly to a “Single vector store of all chunks vectors.” This is a more direct semantic search if the query is straightforward and the knowledge base is relatively flat or well-suited for direct chunk retrieval.

- Retrieval: The selected index performs the retrieval operation, yielding “Top k relevant chunks.”

- Answer Generation: The retrieved chunks are then passed to the LLM to generate the “Answer.”

Key Components:

- Query Router: The central component that analyzes the query and decides the retrieval path.

- Multiple Indices: Different specialized or structured indices (e.g., “Index of summary vectors,” “Single vector store of all chunks vectors”) that the query can be routed to.

- Routing Logic: The intelligence (rules, classifiers, LLMs) that determines which index to use.

Advantages:

- Efficiency: Directs queries to the most relevant and often smaller subset of the knowledge base, improving retrieval speed.

- Scalability: Allows for the growth of diverse knowledge bases without creating a monolithic index.

- Improved Relevance: By using specialized indices, the retrieved context is more likely to be highly relevant to the query’s specific intent.

- Resource Optimization: Different indices might have different computational requirements; routing allows for optimal resource allocation.

Disadvantages/Considerations:

- Routing Accuracy: The effectiveness hinges on the router’s ability to correctly classify and direct queries. Misrouting leads to poor results.

- Maintenance: Requires ongoing maintenance of routing rules or training data for the router.

- Cold Start Problem: New types of queries or documents might not be handled well until the routing logic is updated.

Use Cases:

- Any RAG system with multiple distinct knowledge domains or data types.

- Platforms offering diverse services: e.g., a platform with separate documentation for software, hardware, and customer service.

- Personalized RAG: Routing queries based on user profiles or preferences to specific knowledge subsets.

- Systems requiring different retrieval strategies for different query types.

Conclusion

The evolution of Retrieval Augmented Generation from basic lookup mechanisms to these advanced techniques marks a significant leap in the capabilities of Large Language Models. By intelligently navigating, transforming, and augmenting the retrieval process, these methodologies empower LLMs to deliver more accurate, relevant, and contextually rich responses than ever before.

From the robust combination of lexical and semantic signals in Hybrid Search to the precise contextual expansion of Sentence Window Retrieval, each technique addresses specific challenges inherent in real-world information retrieval. Agents + Query Routing and Hierarchical Index Retrieval provide scalable solutions for managing vast and diverse knowledge bases, ensuring efficiency and specialization. Parent-Child Chunks Retrieval elegantly balances retrieval precision with comprehensive context, while Query Transformation and HyDE Retrieval proactively enhance query quality to bridge the gap between user intent and document content. Finally, integrating Metadata allows for fine-grained control and filtering, adding a layer of factual and conditional accuracy.

Implementing these advanced RAG techniques requires careful consideration of the specific application, data characteristics, and computational resources. However, the benefits — including reduced hallucinations, improved factual grounding, enhanced user experience, and greater scalability — make them indispensable tools for building the next generation of intelligent systems powered by Large Language Models. As LLMs continue to advance, so too will the sophistication of RAG, fostering a symbiotic relationship that unlocks their full potential in an ever-expanding landscape of information.

Discover more from SkillWisor

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.